—Election 2020—

—Remember to VOTE!—

by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

Today’s elections, nearly everyone agrees, have become fiercely, even bitterly, partisan. In 1860, as southern states teetered toward secession, the presidential race divided along partisan and regional lines. Republicans, who were from the north and west, supported Abraham Lincoln, while Democrats split north and south; the former followed Stephen Douglas and the latter John Breckinridge. John Bell, the third party Constitutional Union candidate, took a few states in the upper south. Yet, in what was a bitter contest, the rhetoric of one of Lincoln’s campaign biographies was deliberately calm and unabashedly high-minded.

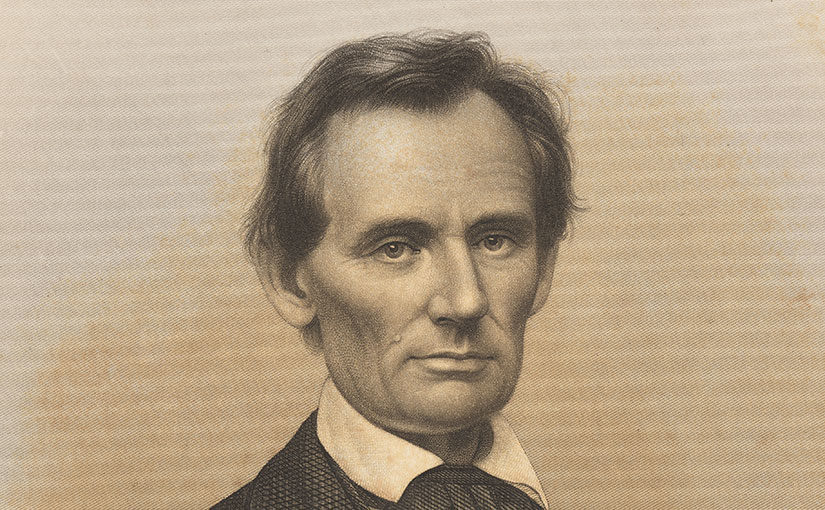

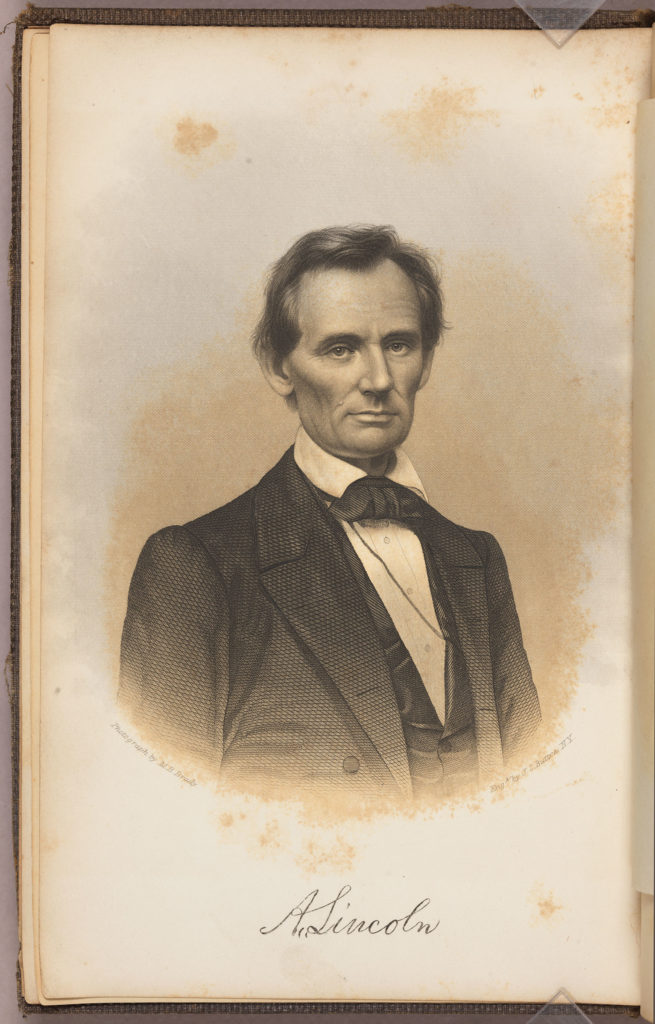

Rare Books and Special Collections holds a scarce piece of campaign literature from the 1860 presidential race—The Lives and Speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin—a book of more than 400 pages that introduced many Americans to Lincoln and his running mate for the first time. Our copy has an original cover and several illustrations, one of which is an engraving of Lincoln based on a photograph taken by Mathew Brady, the New York City photographer.

The volume appeared immediately after the June Republican convention in Chicago, where Lincoln had been chosen as the party’s presidential candidate. It contained a short biography of Lincoln written by a very young William Dean Howells (1837-1920), who would in later years, become a writer, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and arbiter of American literature. The Lives and Speeches also held selected speeches of both men, including Lincoln’s February 1860 speech at the Cooper Institute in New York City, where he laid out his argument that slavery must not extend into the western territories. He ended with the stirring refrain, “Let us have faith that right makes might . . . let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” (p. 213)

Howells, who was at the time a 23 year-old journalist in Columbus, Ohio, interviewed people close to Lincoln to create a portrait of the candidate that emphasized the party’s Free Soil ideas. From friends who knew Lincoln since he was in his early 20s, Howells offered a narrative that included Lincoln’s self-made story, but also impressed on readers that the candidate had been supported along the way by people who recognized his abilities and character. After explaining in some detail how Lincoln had honored a financial debt as a young (and still poor) man, Howells summed up the incident with partisan boosterism, “that the old neighbors and friends of such a man should regard him with an affection and faith little short of man-worship, is the logical result of a life singularly pure, and an integrity without flaw.” (p. 43)

A few pages later Howells summed up his research by assuring his readers, “by the testimony of all, and in the memory of everyone who has known him, Lincoln is a pure, candid, and upright man, unblemished by those vices which so often disfigure greatness, utterly incapable of falsehood, and without one base or sordid trait.” (p. 48)

Howells also took pains to reassure readers, for whom Lincoln was relatively unknown outside of Illinois, that his opposition to slavery was long-standing, clear, and aligned with the Republican party’s 1860 platform. As proof, Howells pointed to an 1837 protest Lincoln had voiced in the Illinois Legislature against a resolution for suppressing abolition societies.

As a campaign piece must, Howells’ biography painted Lincoln as the principled candidate. Howells declared, “throughout his Congressional career, you find him the bold advocate of the principles which he believed to be right. He never dodged a vote. He never minced matters with his opponents.” (p. 57) Howells underscored Lincoln’s exemplary public record through his speeches, which gave the impression that “he has not argued to gain a point, but to show the truth; that it is not Lincoln that he wishes to sustain, but Lincoln’s principles.” (p. 65) To drive home the point that the candidate’s character connected to the presidency, Howells quoted Lincoln directly. “[Slavery],” Lincoln said, “forces so many really good men among ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticising the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.”’ (pp. 75-76) For Lincoln, the Declaration of Independence, in which “all men are created equal,” was the nation’s foundational document and this ideal drove his ambition and service.

In a four-way race, Lincoln won less than 40% of the popular vote but 180 of 303 electoral votes, a decisive victory.