By Maren Rozumalski, Gladys Brooks Conservation Fellow

The recent acquisition of a late Byzantine Greek manuscript fragment gives us an excellent opportunity to highlight the relationship between Rare Books and Special Collections and the library’s Analog Preservation Department.

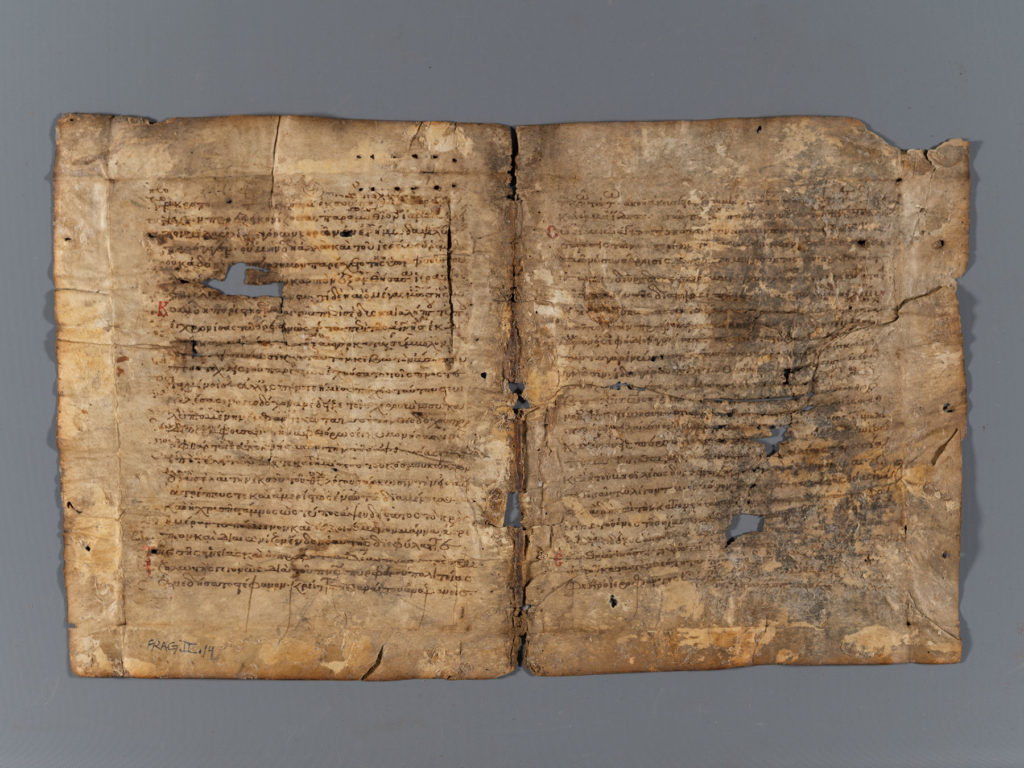

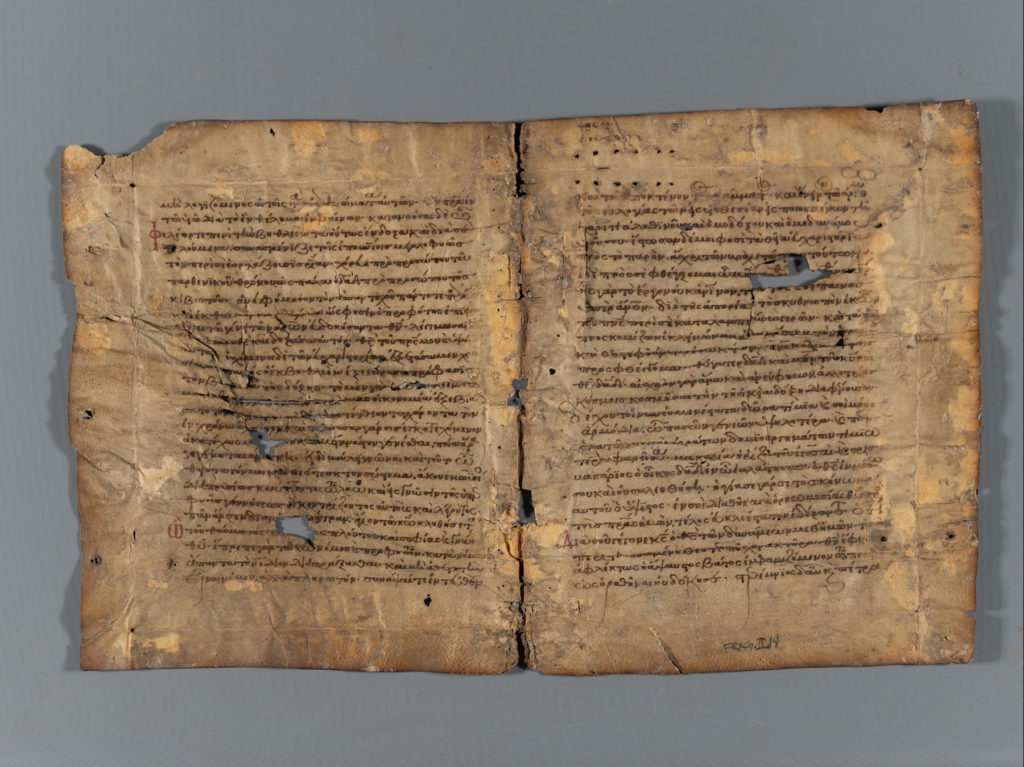

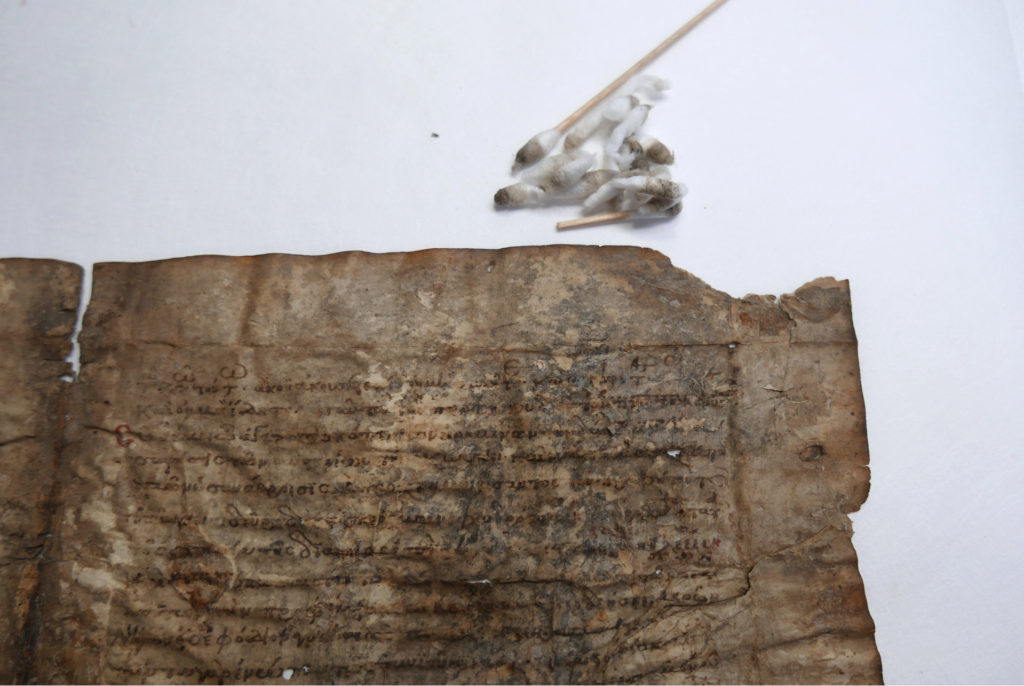

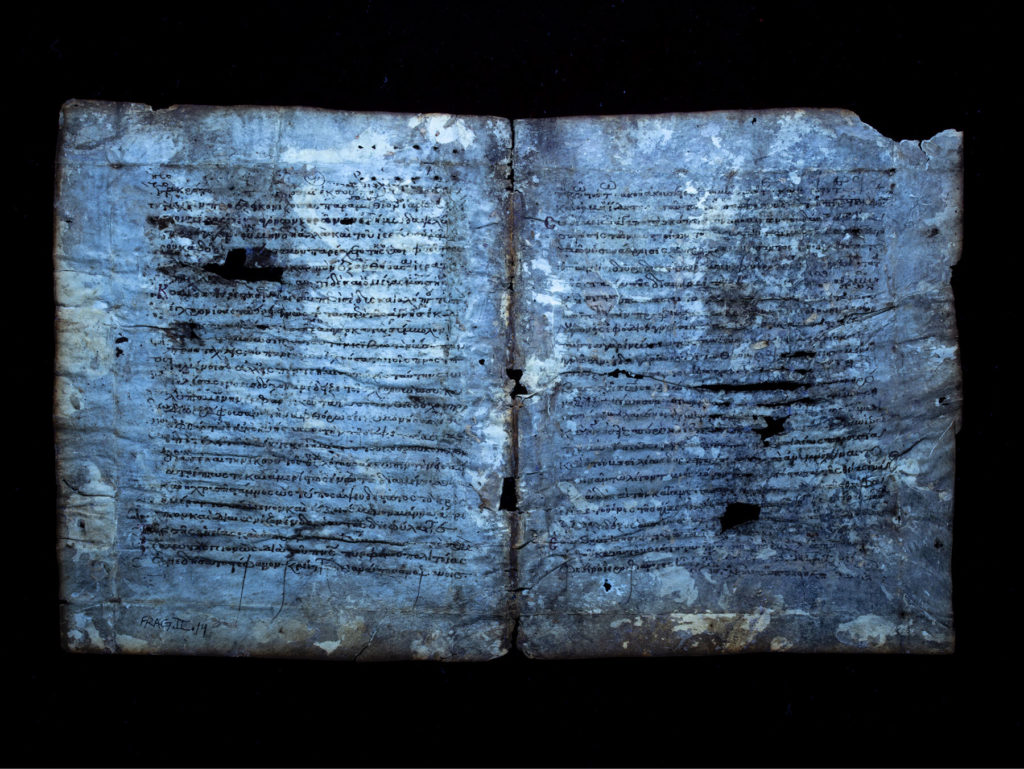

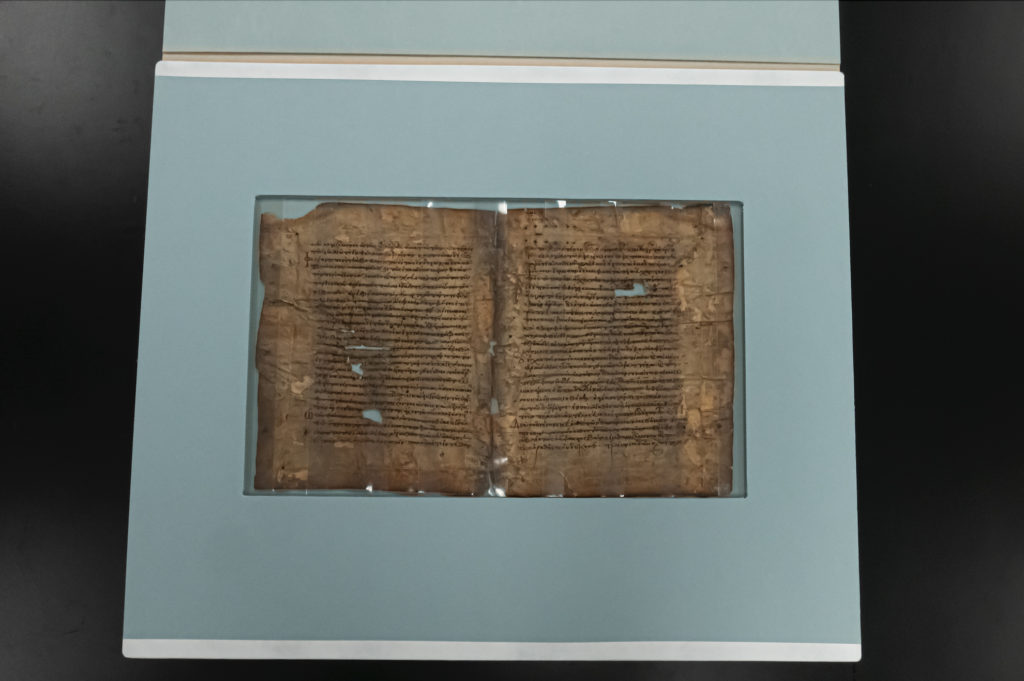

The fragment is a single sheet of parchment, approximately ten inches tall by sixteen inches wide, folded down the center to create a bifolium. It is written on both sides in iron gall ink with red pigment initials. This piece is believed to be from the 13th-14th century and is yet to be identified fully. Initial studies indicate it contains sermon extracts, but the exact genre of the manuscript is unknown; all texts are unidentified currently. It will primarily be used in the teaching of graduate level Greek Paleography.

The fragment came to the library in a delicate state. It has not lived an ideal life over the centuries, and as such, it was important to have the preservation department evaluate its condition before it was allowed to be handled in classes and by researchers. One of the main issues was that some of the text was obscured due to creases resulting from moisture damage. Moisture damage is problematic when dealing with parchment, because it is not reversable and any moisture introduced during treatment has the potential of furthering the degradation.

Microscopic examination of the parchment confirmed that it has water damage and that the degradation and darkening were at least partially due to mold damage. There was no evidence of active mold. Magnification also revealed that the surface layer of parchment on the flesh side of the parchment was lifting and flaking off in the areas with the most degraded areas.

Together with RBSC, the following treatment goals were decided:

1. Flatten the parchment to reveal the obscured text where possible.

2. Remove staining to improve text legibility as needed, and where possible.

3. Mend tears and areas of loss to stabilize the fragment.

4. Provide housing for handling and storage support.

Each treatment was done selectively, so that the parchment was as undisturbed as possible and other treatment goals could be accomplished. This approach is best for the longevity of the parchment and also leaves the possibility of a theoretical codicological reconstruction to determine the original construction of the codex to which this fragment once belonged.

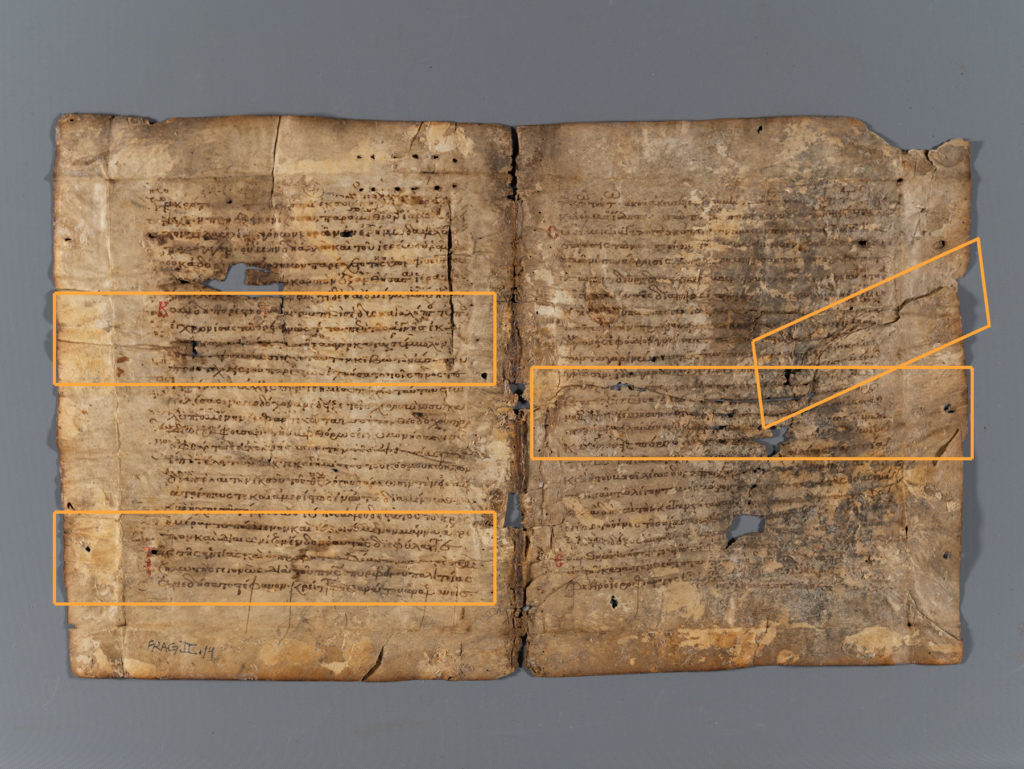

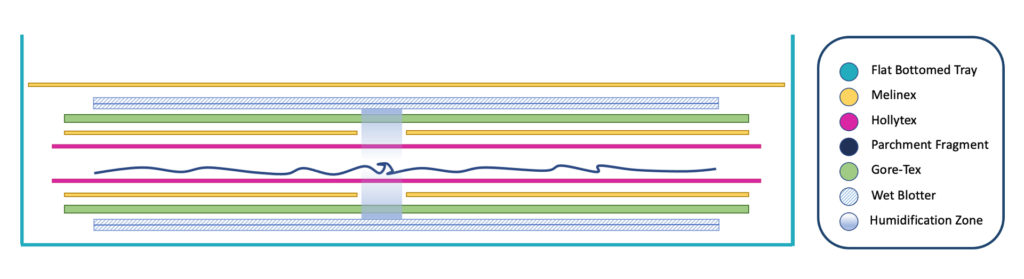

Four zones were identified as needing “flattening” (more like gentle stretching) to gain access to the obscured text. Humidification, though not ideal, was deemed the only option. A system was devised which allowed each zone to be humidified in isolation. I settled on a Gortex pack sandwich method, which introduced the moisture evenly from both sides of the parchment. This way the parchment became workable more quickly than if moisture were only being introduced from one side and needed to permeate all the way through. Each area was humidified until it was pliable, but never felt wet. The parchment was gently stretched once it was workable and held in its new position as it dried. The stretching worked better in some areas than others, but all of the text is now partially visible making the text more visible.

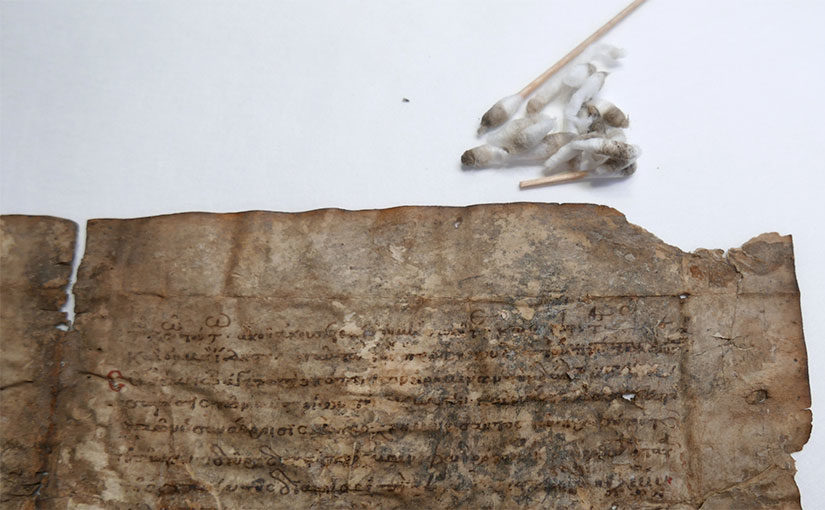

The darkest areas of parchment with text were surface cleaned with a 50/50 solution of ethanol and deionized water. A damp cotton swab was rolled over the lines of text, lifting up the surface dirt as it went. The ethanol in the mix helped the water evaporate more quickly so it would soak into the damaged parchment.

A patch of parchment roughly the size of a quarter was lifting and about to pop off the document. This was consolidated using a 3% gelatin mousse, which is comprised of cold gelatin strained through a very fine sieve until it is light and frothy. Gelatin mousse is much easier to control than liquid gelatin since it stays in place after brushing, and because as a drier adhesive it does not permeate the substraight as much as other adhesives.

The tear repairs and bridge mends were done using pre-coated tissue made with wheat starch paste that was reactivated using the same gelatin mousse. The repairs were done on both sides of the parchment so a thin translucent paper could be used but the repairs would still be strong.

UV photography was the last step before making permanent housing for the fragment. Iron gall ink appears darker in UV light than it does in visible light, so the Greek text will be easier to read in UV photographs than in normal light photos or in person. These photographs will aid users working with the fragment.

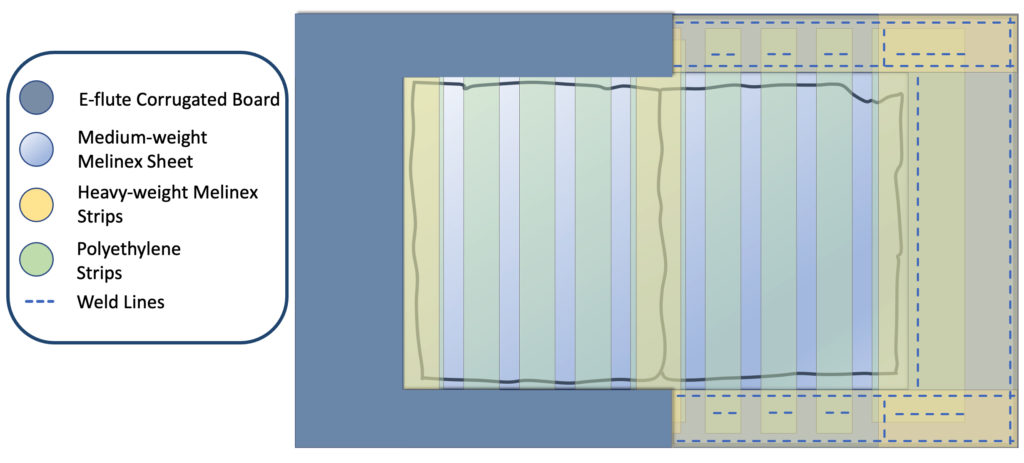

The final challenge before returning the fragment was housing. Developing a housing system was the most important aspect of this treatment so the fragment can safely maintain its active life. After experimenting with several models, a double-sided window mount was designed, which I adapted from the British Library’s housing for burnt fragments from the collection of Sir Robert Cotton. The parchment is contained within a packet of polyethylene strips and various weights of polyester sheeting. The strips on one side instead of two solid sheets allow for plenty of airflow so there is no danger of creating microclimates. This also helps minimize polyester’s tendency toward static electricity build-up. The fragment was then secured between two window mattes made of corrugated board.

All of the treatment goals were reached using a “less is more” approach, and sturdy housing was constructed. The fragment is back in the library ready for active use.