by Julia A. Schneider, Ph.D, German Language & Literature Subject Liaison

“Most journalists have the intractable purpose of reshaping the times according to their system, not reshaping their system according to the times.” 1

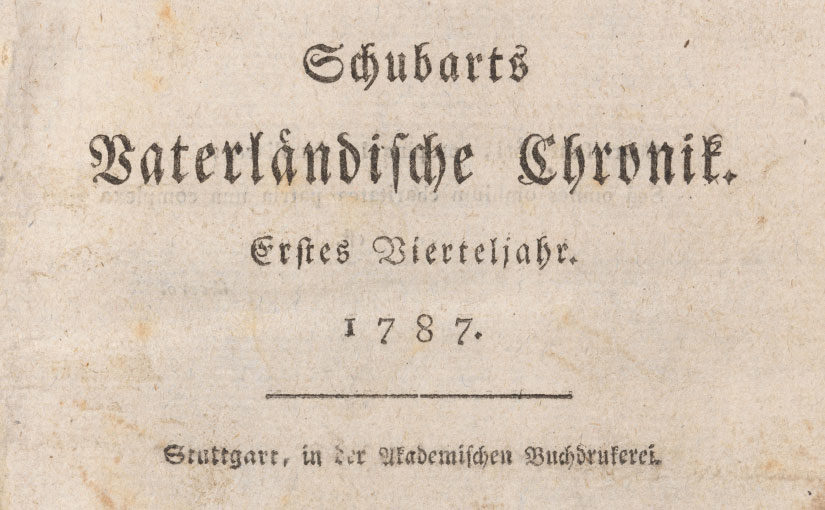

This two-line manifesto by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (March 24, 1739-October 10,1791), the publisher of the Vaterländische Chronik (also known as the Deutsche Chronik and Teutsche Chronik in its earliest incarnation), shows how his approach to both journalism and “the times” of the late eighteenth century may have differed from that of other, contemporary publishers. Contents of the Chronik, from the beginning, were not limited to simply reporting in dispatches, narrative descriptions, or just-the-facts observations, but included opinions, commentary, poetry, and other types of prose. Published from 1774-1778 and again from 1787-1791, the Chronik had a circulation of about 4000 per issue at its height.2

Schubart had been a schoolmaster, was considered a keyboard virtuoso, and had influence on Enlightenment poets like Goethe and Schiller. He considered himself a patriot, and provided incisive commentary on the way that rulers wielded their power, as well as the way that some authority figures used superstition to maintain or increase their own positions. As a patriot himself and a believer in a freer society, he also took a great interest in the conflict in the colonies that became the American Revolution.3 He was imprisoned in 1777 in the fortress of Hohenasperg on the orders of the Duke of Wurttemberg, in part due to Schubart’s printing of the rumor (as “legend”) that the duke was lending 3000 troops to England to fight the revolutionaries in North America; Schubart had already reported the selling of troops by other nobles to the British. He remained imprisoned, initially under deplorable conditions—without a trial—for more than ten years. Although he continued to write poetry from prison, even while subject to a re-education program under the tutelage of a pietist and archenemy (“Intimfeind” in German) whom Schubart had frequently criticized in print.4

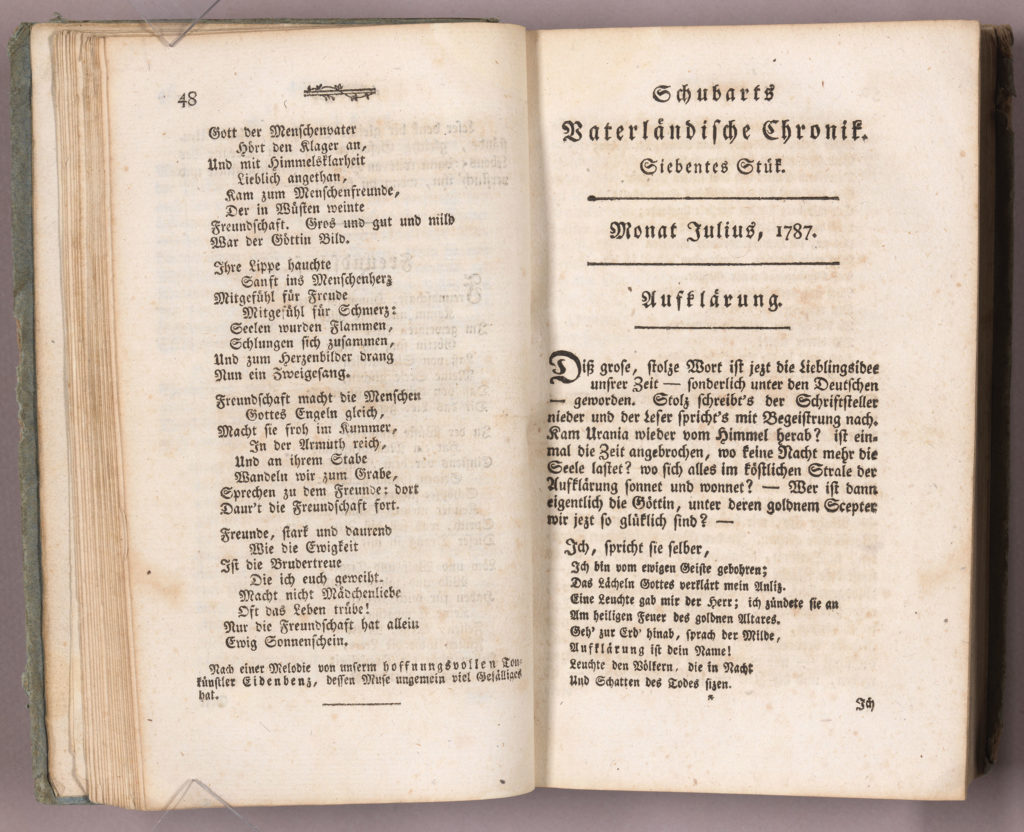

Notre Dame’s copy (Rare Books Small DD 193 .S35 1787/1788), was published under the title used after his imprisonment, Vaterländische Chronik. It covers the last half of 1787, including the July and December quarterly issues. Perusing this later segment of the Chronik allows the reader entry into Schubart’s perspective and publishing program after his imprisonment. By choosing several pieces, we can see examples of the way his views did and did not alter during this time of extreme stress and so-called “re-education.”

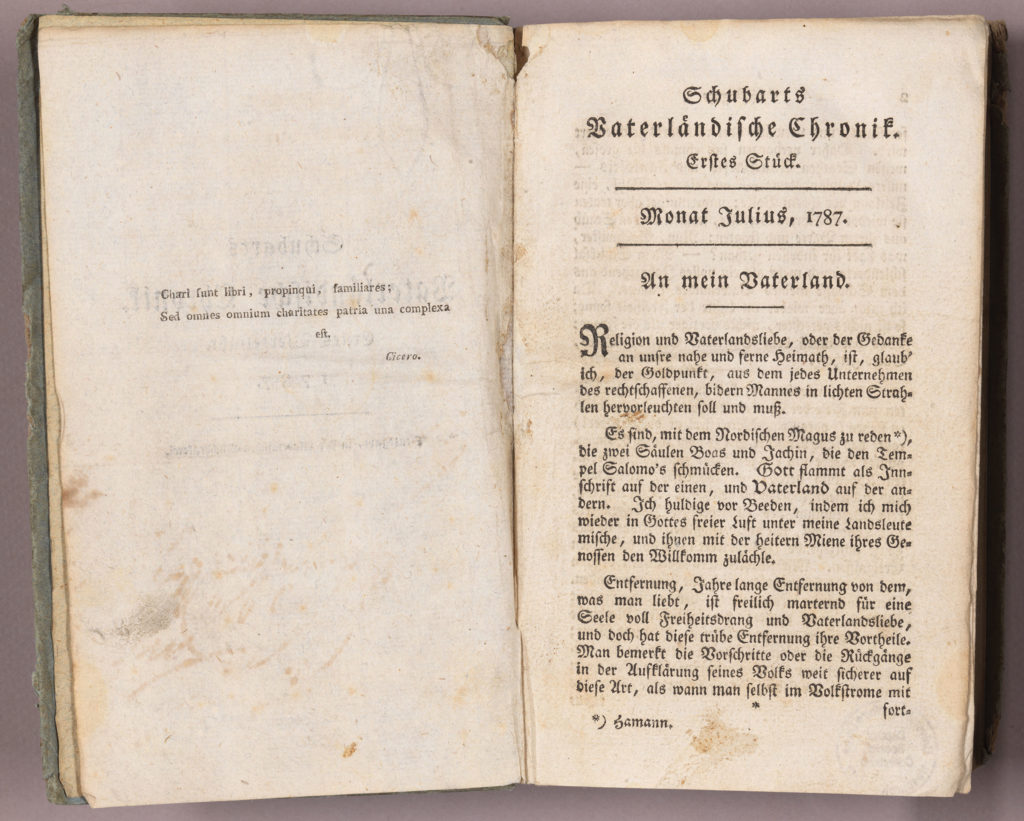

In the piece at the beginning of the July issue (erstes Stück) “In mein Vaterland” shows, where Schubart draws a comparison between the pillars of flame and cloud that led the Israelites from their imprisonment to their homeland and his own experience of prison and release into the type of freedom among his fellow citizens that awaited him in his own homeland. Unlike mere metaphorical, poetically emotional understanding of restraint presented in the work of Romantics, Schubart provides experience of the outside world that only someone who had experienced imprisonment could understand.

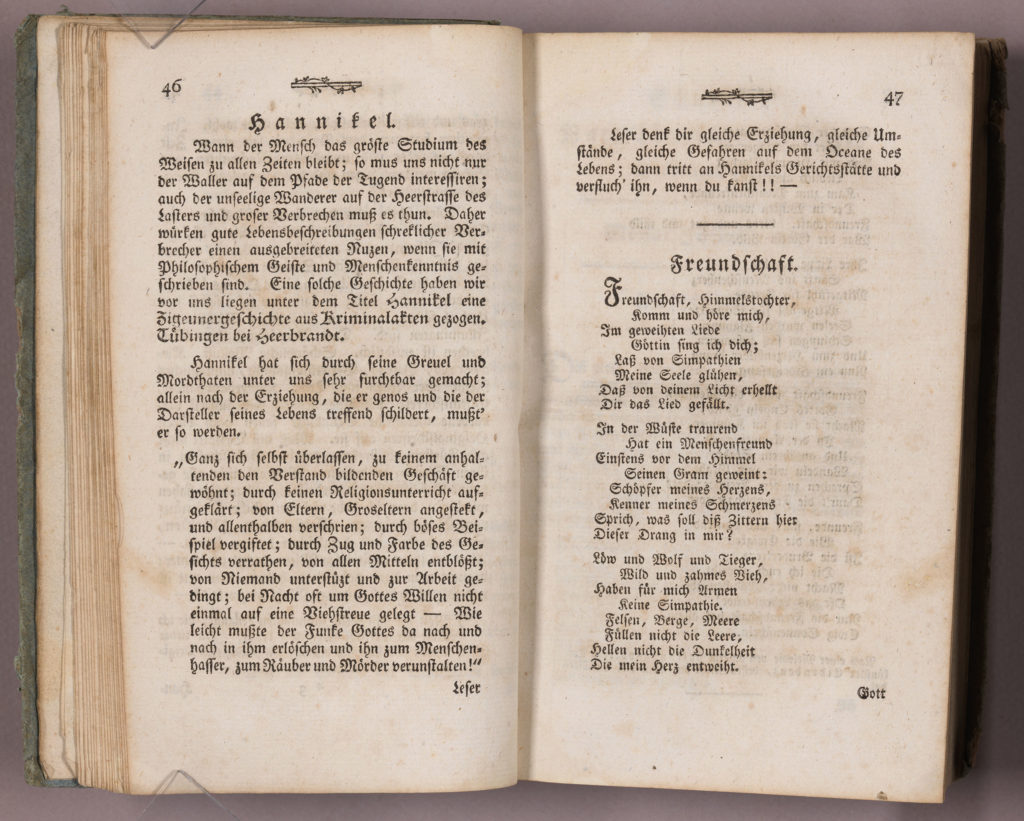

Schubart later reports the case of the well known robber Hannikel, whose gang was responsible for multiple thefts and murders over the period of decades, resulting in their execution by hanging in July of 1787. Hannikel eventually became a character who appears in the costumed festival Fasching which occurs before the beginning of Lent. Schubart’s report shows that, even before his death, Hannikel may have been thought of in a somewhat positive light, because Schubart’s short piece includes admonishing commentary about the creation of a “legend” about the thief when, in reality, those who leave the path of goodness, preferring to take the road of lies and degradation, are not to be commended, especially when that degradation includes the plunder, injury, and murder of unsuspecting travelers. Following this report is his own poem “Freundschaft,” on the ideal of friendship.

Finally, in the seventh part of the July 1787 issue (Siebentes Stück), we see his thought-piece, “Aufklarung” (“On the Enlightenment”), where he draws on contemporary poetry about the spirit of enlightenment to discuss the principles of enlightened thought. This allowed Schubart to return to the intellectual point of mediation between the Sturm und Drang proponents of the Enlightenment and their severest critics, forging a position which embraced lofty ideals but wished to harness them in educational and political reality, to the benefit of his fellow citizens. This and the foregoing examples from Notre Dame’s volume of the Chronik provide insight into the thought and work of a now lesser-known German poet and journalist, one whose own life was also worthy of observation and report.

Footnotes

1. “[D]ie meisten Journalisten haben die hartknäckigen Vorsatz, die Zeiten nach ihrem System und nicht ihr System nach den Zeiten umzubilden.” Christian Friedrich Schubart, ed. Deutsche Chronik, Jahrgange 1774-1777 (4 Bde), Heidelberg, 1975, 1:3, cited in Wolfgang Albrecht, “Aufklärungstrategien in Schubarts Chronik, 1774-1776 (in Potthast, ed., Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart- Das Werk, Heidelberg, 2016, pp.171-94), 172, n. 7.

2. Hartmann, Alexander. “Christian Daniel Friedrich Schubart Jounalist, Musiker, und Dichter der Freiheit,” in Neuen Solidarität, 51 1999 (https://www.schiller-institut.de/jahr2005/essays/schubart.pdf, accessed January 13, 2023), translated by Daniel Platt as “Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart- Journalist, Musician, and Poet of Freedom,” October 2014, https://archive.schillerinstitute.com/educ/hist/2014/hartmann-schubart_bio.html (accessed January 13, 2023).

3. The German public was intensely interested in the goings on in North America, especially due to the involvement of former Prussian army advisor, Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who was in great part responsible for the professionalization and training of the colonial troops at Valley Forge and remained an advisor to George Washington after the war, serving as inspector General of the Military. He was the author of Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States.

4. Hartmann, op. cit.