Cusack’s Life of Saint Patrick

with Hennessy’s Tripartite Life of St. Patrick

by Aedín Ní Bhróithe Clements, Irish Studies Librarian

Visitors to the Special Collections usually notice our stained glass picture of Saint Patrick. However, this is far from the only reference to Ireland’s patron saint in the Special Collections. Among the many books, pamphlets and prints relating to Patrick, we have this Life of Saint Patrick, written by a woman known variously as the Nun of Kenmare, Margaret Anna Cusack, or Sister Mary Francis Cusack.

Visitors to the Special Collections usually notice our stained glass picture of Saint Patrick. However, this is far from the only reference to Ireland’s patron saint in the Special Collections. Among the many books, pamphlets and prints relating to Patrick, we have this Life of Saint Patrick, written by a woman known variously as the Nun of Kenmare, Margaret Anna Cusack, or Sister Mary Francis Cusack.

Sister Mary Francis Cusack, a prolific writer on Ireland and on the Catholic faith, was born in 1829. She grew up in County Dublin and also in England where she joined an Anglican religious order. In 1858 she converted to Catholicism and joined the Poor Clare order. [1]

In 1861, Cusack was among the founders of a new community of Poor Clares in Kenmare, County Kerry. In Kenmare, Cusack began to publish her writings, and became a well-known writer among Irish Catholics. Her writings found a market among Irish-American Catholics, contributed greatly to the convent’s income. She remained in Kenmare until 1880, and traveled to Knock, County Mayo, the site of an apparition in 1879. There she attempted to found a convent and industrial school. This endeavor failed, and she left for England.

In England, she established a new order, St. Joseph’s Sisters of Peace, with convents in Nottingham and Grimsby. She later moved to the United States and opened an American mother-house of the order, but this met with little success. Having had difficulty in her dealings with bishops, Cusack resigned from the order and left her convent. She left the Catholic Church and was a Methodist until her death in 1899.

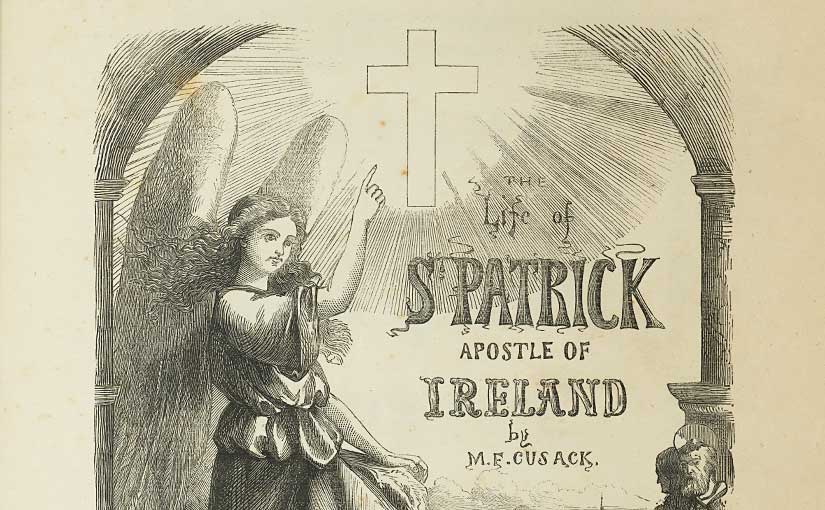

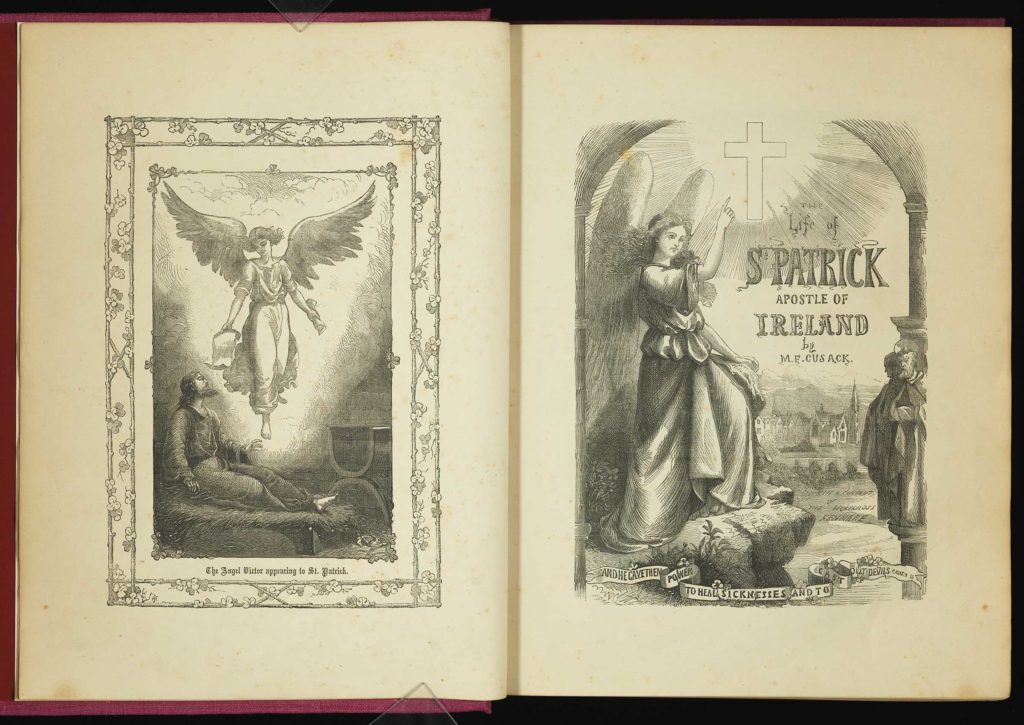

The Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland was written while she was Sister Mary Francis Cusack, published in 1871, and clearly intended for a wide readership as the title page lists publishers in London, Dublin, Boston and Australia. The first edition had apparently been published in Kenmare, County Kerry in 1869, with an American Catholic publishing house listed also on the title page. [2]

The saint’s life, as explained by Cusack, who argues that Patrick was a Catholic, and emphasizes his miracles, takes up the first 368 pages of this book and includes many illustrations. Each page is framed in a decorative border. In fact, the book would be a handsome addition to any home library.

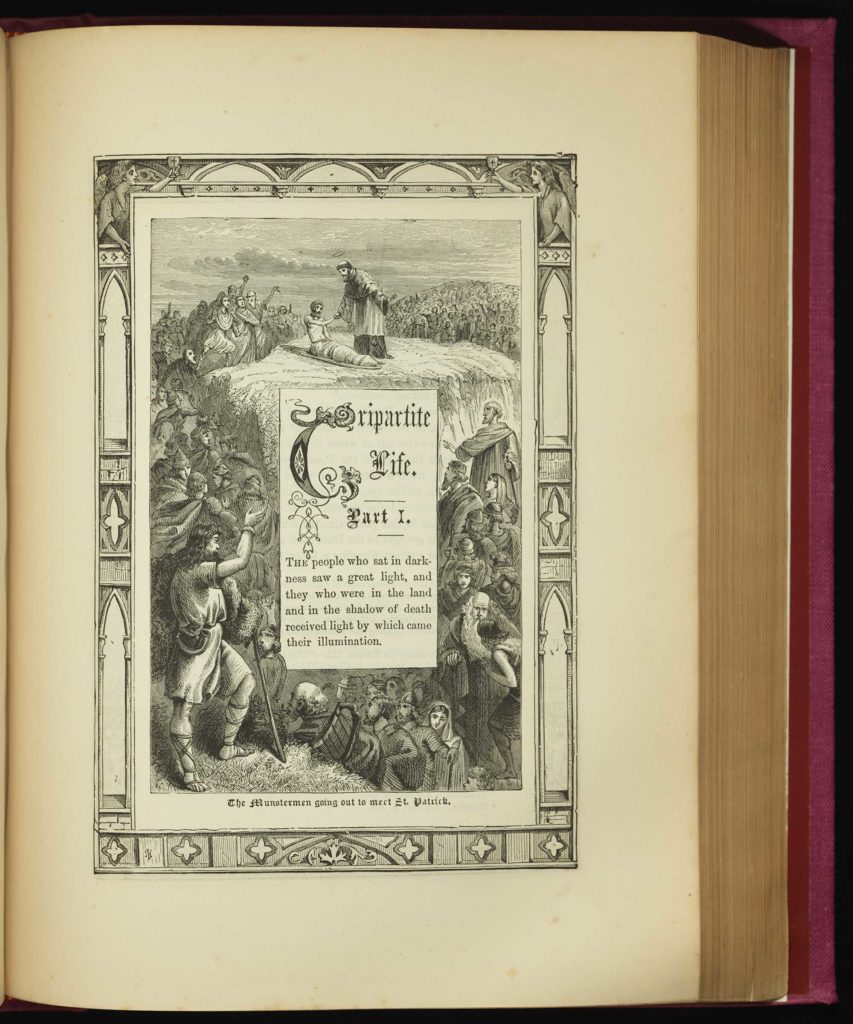

‘The Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland’, pages 369 to 502 of this book, is, according to the title page of this section, translated from the original Irish by W. M. Hennessy.

While nowadays we expect a scholarly translation of old manuscripts to include introductory information outlining the sources used and the language of those sources, this information is difficult to glean from Hennessy’s translation. William Maunsel Hennessy (c. 1829-1899), was a highly-regarded scholar of Celtic studies and of Irish manuscript literature.

Hennessy’s text here is an edition translated from manuscript sources dating from about one thousand years earlier, and therefore in Old Irish, quite different from the language spoken in the nineteenth century. While Hennessy does not specify his sources, Cusack, in her introductory chapters, describes the various accounts of St. Patrick’s life found in the Book of Armagh, of which she states that the Tripartite Life is the most important. She also mentions that it is regrettable that the Book of Armagh is now in a Protestant institution, Trinity College, but on balance, it is a good thing that it is safe and well cared-for.

In Hennessy’s text, he occasionally alludes to his manuscript sources, for example, following the story of Patrick and his sisters being sold as slaves in Ireland, the author states that a leaf is missing from both the Bodleian and British Museum MSS. of the Tripartite Life.

The text describes many miracles carried out by Patrick, from boyhood on. The following passage describes the event where Patrick is said to have lit a fire in defiance of the king.

As the people of Tara were thus, they saw the consecrated Easter fire at a distance, which Patrick had lighted. It illuminated all Magh-Bregh. Then the king said, “That is a violation of my prohibition and law; and do you ascertain who did it.” “We see the fire,” said the druids, “and we know the night in which it is made. If it is not extinguished before morning,” added they, “it will never be extinguished. The man who lighted it will surpass the kings and princes, unless he is prevented.” When the king heard this thing, he was much infuriated. Then the king siad, “That is not how it shall be; but we will go,” said he, “until we slay the man who lighted the fire.”

…..

The druid Luchat Mael put a drop of poison into the goblet which was beside Patrick, that he might see what Patrick would do in regard to it. Patrick observed this act, and he blessed the goblet, and the ale adhered to it, and he turned the goblet upside-down afterwards, and the poison which the druid put into it fell out of it. Patrick blessed the goblet again, and the ale changed into its natural state. [3]

This Life of Saint Patrick calls out to be examined and researched. This lavishly-produced book invites questions about the readership and intended audience, the sources used, and many other questions. In fact, writing this blogpost was challenging because exploring the book raised more questions than answers. Where did the illustrations come from? Did W. M. Hennessy publish this translation anywhere else, and what were his manuscript sources? Who purchased copies of this book? As is the case with many of our books, a visit to the Rare Books and Special Collections to view this book up close would be very rewarding.

[1] Patrick Maume. “Cusack, Margaret Anna (‘The nun of Kenmare’)”. Dictionary of Irish Biography. James McGuire, James Quinn. (ed.) Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[2] The 1869 edition may be viewed in Hathi Trust.

[3] Hennessy, M. F. ‘The Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick’, in Cusack, p. 385-388.