by Anne Elise Crafton, PhD, RBSC Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Hesburgh Libraries

As the 2024-2025 Rare Books and Special Collections Postdoctoral Research Fellow, I learn something new about the Hesburgh Library’s diverse collections every day. This is especially true of my primary research project: the description and arrangement of the library’s hitherto uncatalogued collection of medieval and early modern charters. The collection includes both public and private documents – primarily concerned with land and land-based transactions – spanning eight centuries and three countries (England, France, and Italy), though the majority are of English origin.

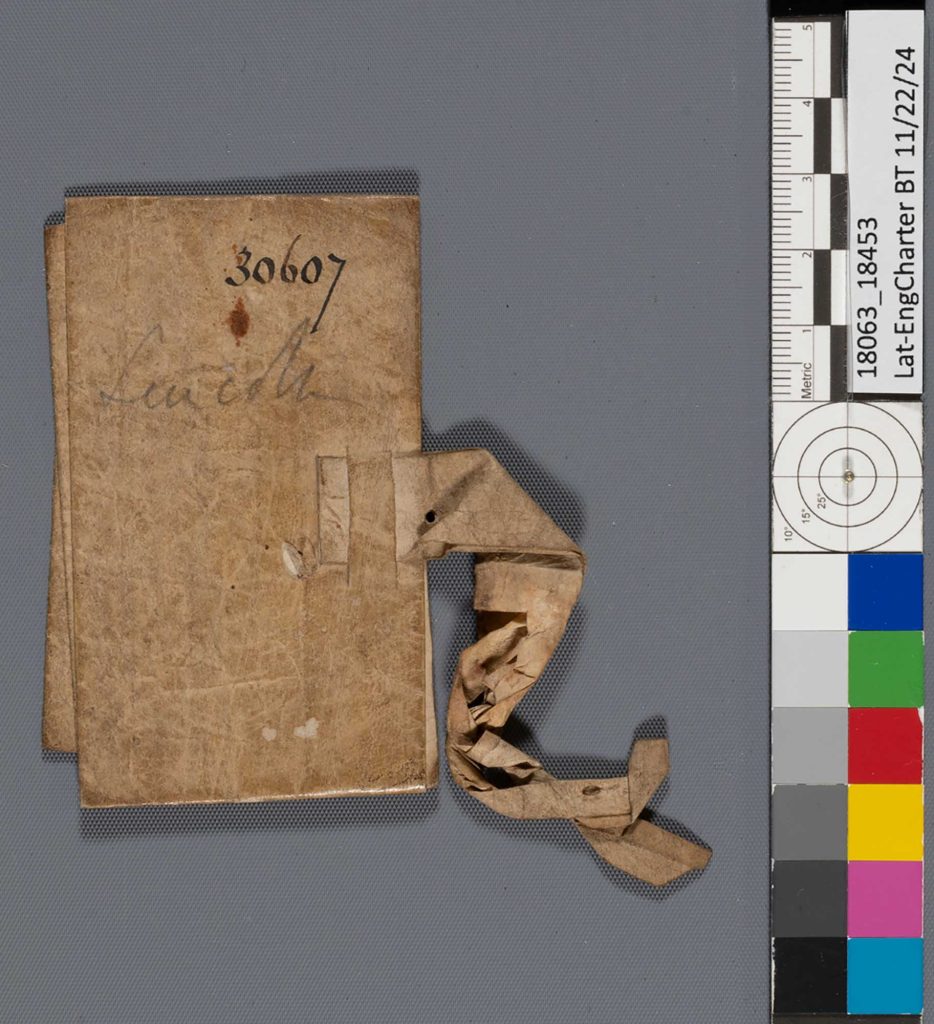

Many of the medieval English charters were part of the vast documentary collection of famous antiquarian and bibliophile, Sir Thomas Philipps (d. 1872). In fact, the iconic “Philipps Numbers” which he used to identify the over 40,000 documents in his collection are still visible on the exterior of many of the charters in the Hesburgh Library’s collection.

This Lincolnshire charter was evidently the 30,607th document to join the extensive Philipps collection. After his death, the collection was eventually disbanded and sold. Now, libraries across the world hold small portions of the once massive collection. Of the Hesburgh Library’s collection of charters, at least thirty-five were once owned by Sir Thomas Philipps.

Philipps was not the first person to annotate these charters before they arrived at the Hesburgh Library. In the Middle Ages, after the transaction was complete, the parties involved would add their personal seals and tightly fold the charter recording the event using a method known as “docketing.” This collection of charters was received in their original docketed form and are currently being flattened for ease of access by Hesburgh Library’s Special Collections Conservator Jen Hunt Jonson. The photos in this post were taken during that ongoing process.

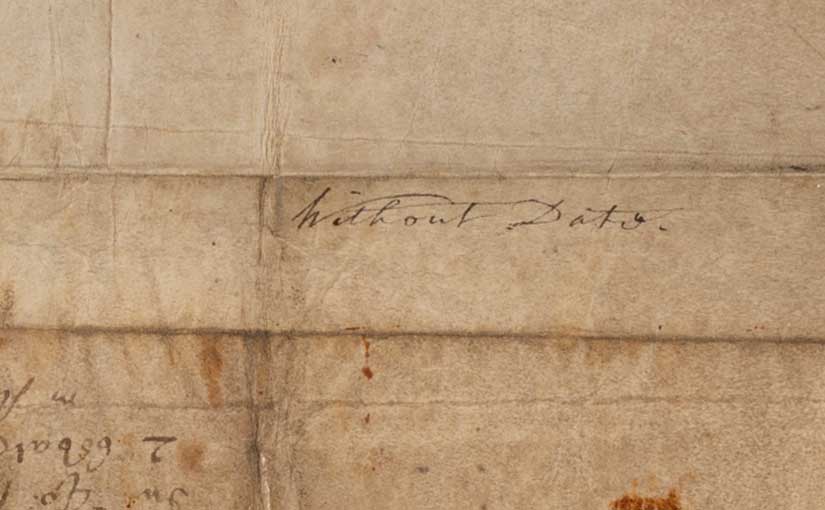

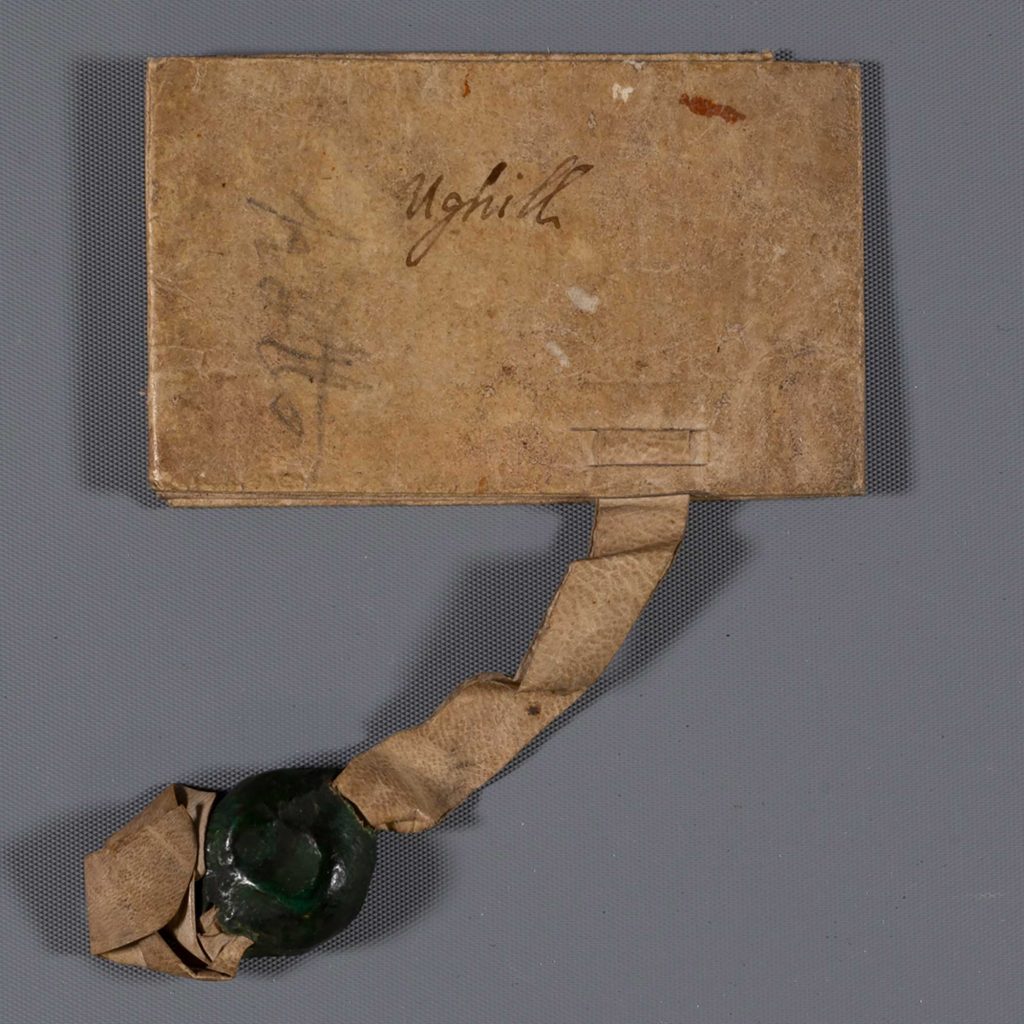

Once docketed, a scribe would label the document, naming the location of the land in question, names of the parties, or the date. If no medieval label existed, early modern archivists might inscribe a label according to their own filing systems.

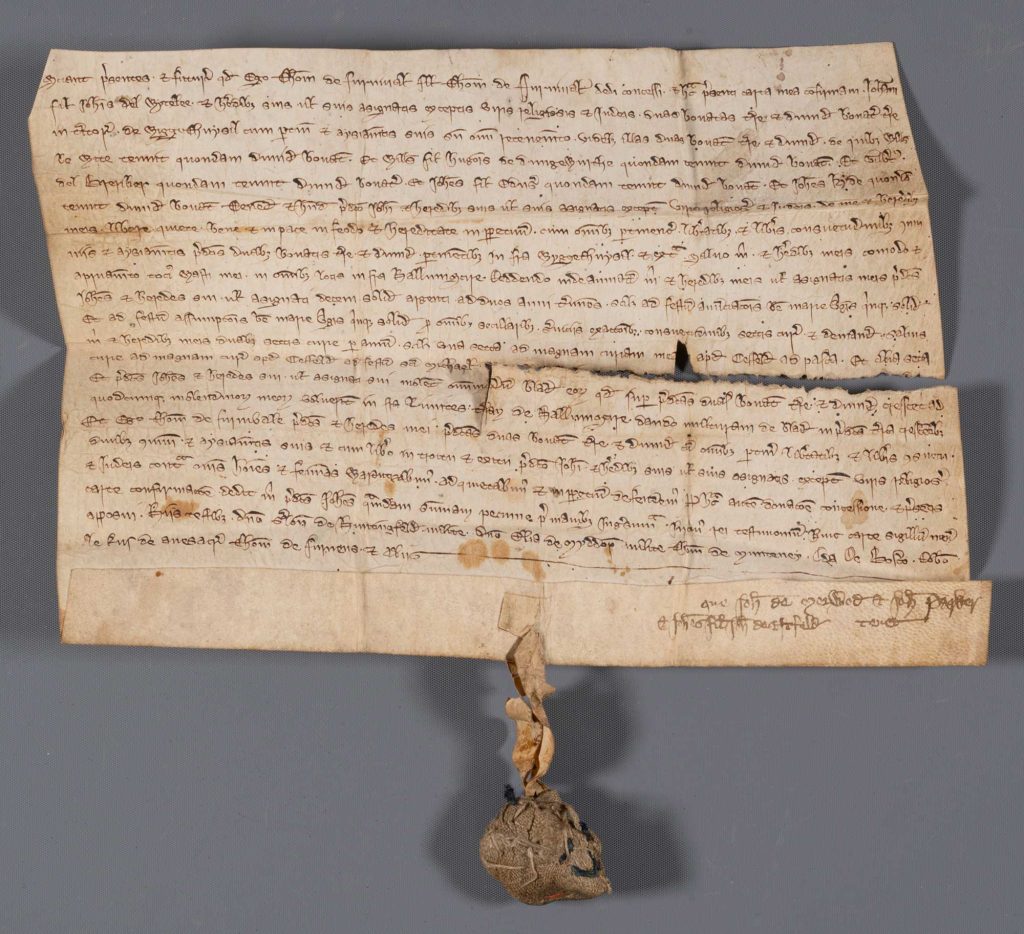

This next charter from the collection, for example, still retains a medieval wax pendent seal bearing an “S” and the word “Ughill,” a small town in Sheffield, Yorkshire, in an early modern hand. This corresponds with the text on the interior, which tells us in Latin that a Richard Schagh granted a tenement in “Ugilwode” to a Thomas Curton in 1377.

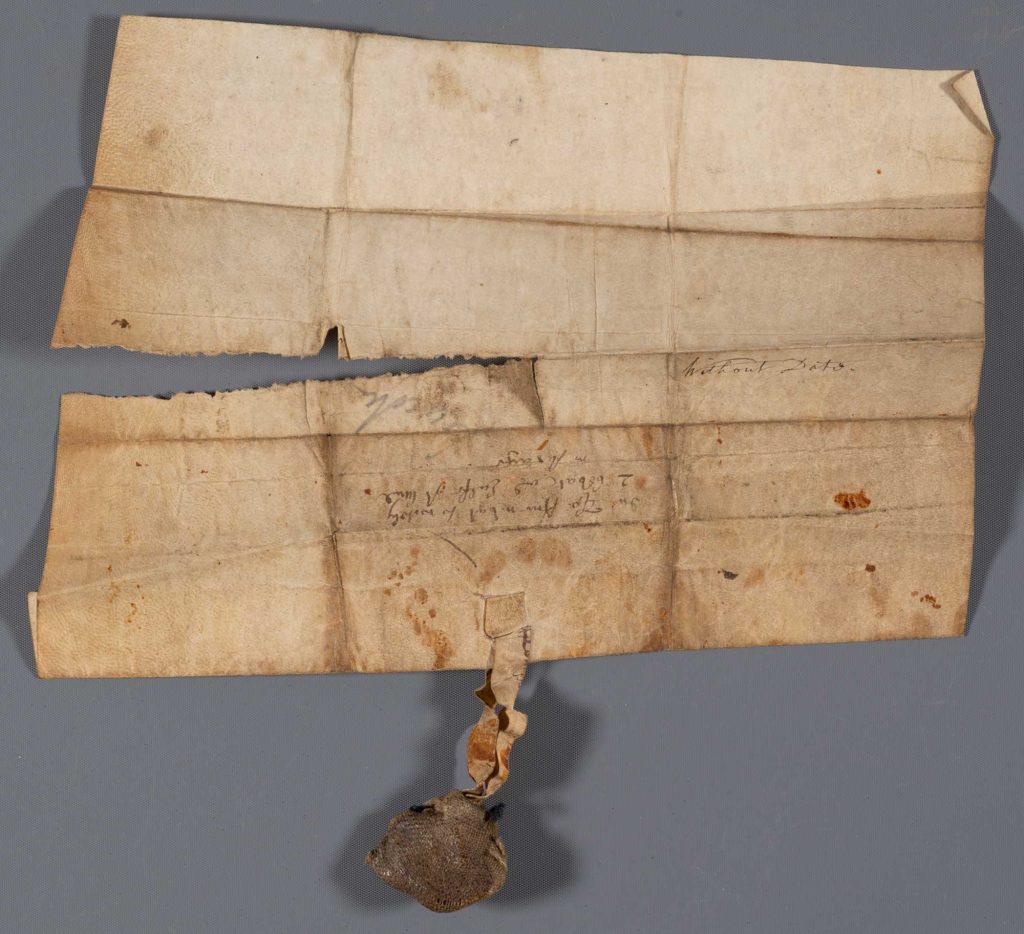

A third charter in the collection also bears an early modern inscription which reads, among other notes, “Without Date.” This is true. The text inside does not include the date of signing, though this is not particularly unusual for medieval English charters. Using modern resources and research, however, it is possible to ascertain a general date of origin.

This particular charter is a “feoffment” – an exchange of land for a pledge of service – between Thomas Furnival, son of Thomas Furnival, and John Witely, son of John Witely concerning lands in “Wiggethuysel” (Wigtwizzle, near Sheffield, Yorkshire). All in all, this charter is extremely typical of medieval English charters; the names “Thomas” and “John” are common medieval names and the contract between them is nothing special. The handwriting – a popular medieval English script known as “Cursiva Anglicana” – only tells us that the charter is medieval and English. There are few clues in the physical material of the charter – like many medieval charters, this document is small, made of soft parchment, and stained with wax.

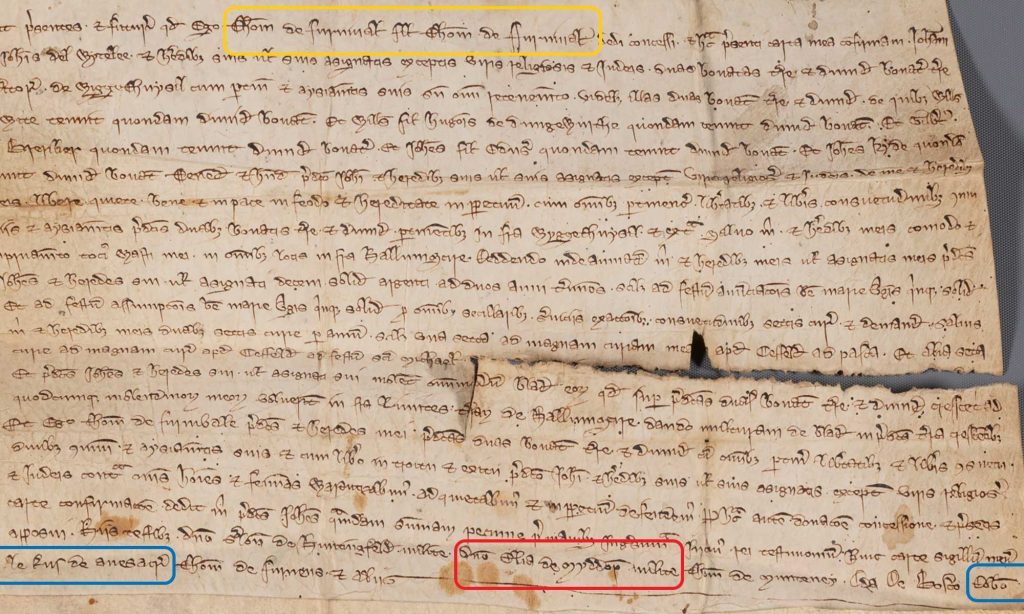

There is, however, a clue in the surname “Furnival” (highlighted in yellow below). In the mid-fourteenth century, the Furnivall family was granted the Barony of Sheffield, Yorkshire and raised to minor nobility. As nobility, the Furnivall family kept detailed genealogical records dating back to the twelfth century.1 Based on these records, we find that there were two “Thomas, son of Thomas” Furnivalls, the first of whom died in 1279, and the second in 1348. This suggests that this document is either from the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century.

We can specify further. Among the witnesses listed in the charter, there is a “Lord Elias Middehop” (in red) and “Robert Rus of Anesacre [Onesacre]” (in blue). According to a catalogue of Sheffield charters, the same Elias Middehop witnessed a separate charter for a Thomas, son of Thomas Furnivall, sometime between 1267-1279.2 Additionally, according to a genealogy of important Yorkshire families, in the late thirteenth century, the daughter of a “Sir Elias Middehop” married the grandson of a “Sir Robert Rus of Onesacre.”3 Altogether, this evidence suggests that the Hesburgh Library charter is probably dated to the late thirteenth century, likely between 1250-1279.

Each charter in the Hesburgh Library collection has similarly rich historical puzzles to unwind. Once catalogued, the collection will be made available for use by students and researchers alike.

Footnotes

1. John Burke, A general and heraldic dictionary of the peerages of England, Ireland, and Scotland, extinct, dormant, and in abeyance, (London, H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1831), 215-217. Special Coll. Reference • CS 422 .B84 1831

2. Walter Hall, Sheffield and Rotherham from the 12th to the 18th Century: A Descriptive Catalogue of Miscellaneous Charters and Other Documents Relating to the Districts of Sheffield and Rotherham with Abstracts of Sheffield Wills, proved at York from 1554 to 1560 And 315 Genealogies Deduced Therefrom, (Sheffield: J. W. Northend, 1916), 210.

3. Joseph Foster, Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire, v. 2 (London: W. Wilfred Head, P L O U O H Court, Fetter Lane, E.G., 1875), 281-282.