by Jacob Swisher, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of History, University of Notre Dame

As fall comes to a close and leaves blanket the landscape, there are still apples fit for picking and ideal carving pumpkins throughout much of Michiana. You may not find any such apples or pumpkins rolling around Rare Books and Special Collections this fall, but a journey into the books from Edward Lee Greene’s personal library is certain to furnish you with some fruity history about the connection between fruit and identity in American history. Edward Lee Greene (1843-1915) was an American botanist whose personal library of over 3,000 volumes is held in Rare Books and Special Collections. Though you won’t encounter a botanical history that explains the pumpkin spice latte in the stacks, Greene’s library does contain an intriguing manual that helps us to think about the role of fruit in American history and our daily lives from the perspective of a state well-known for its horticulture: California.

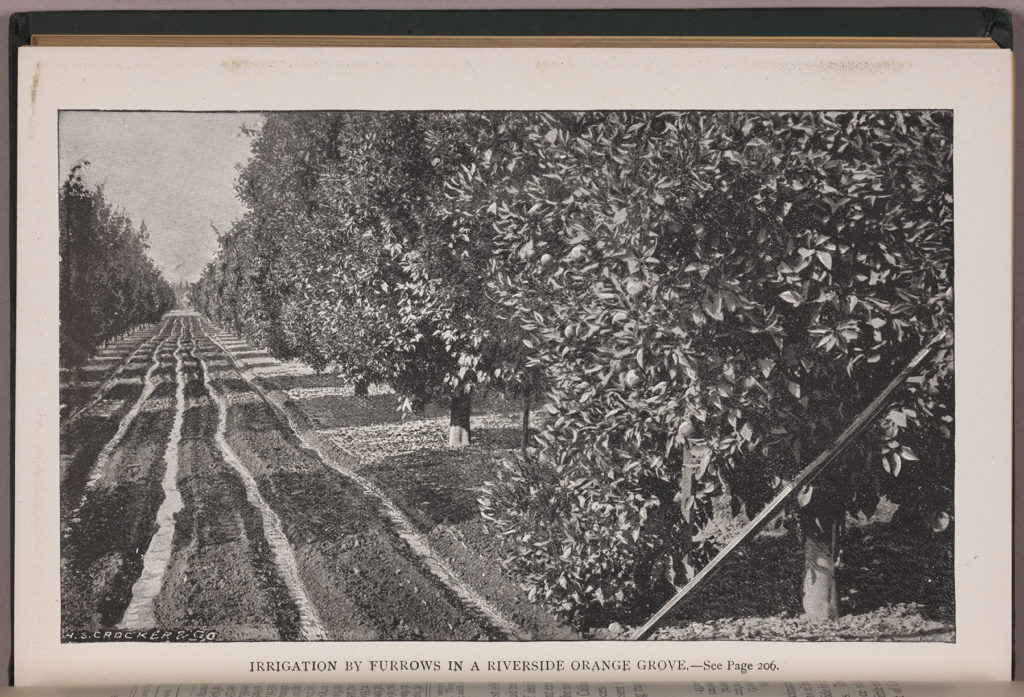

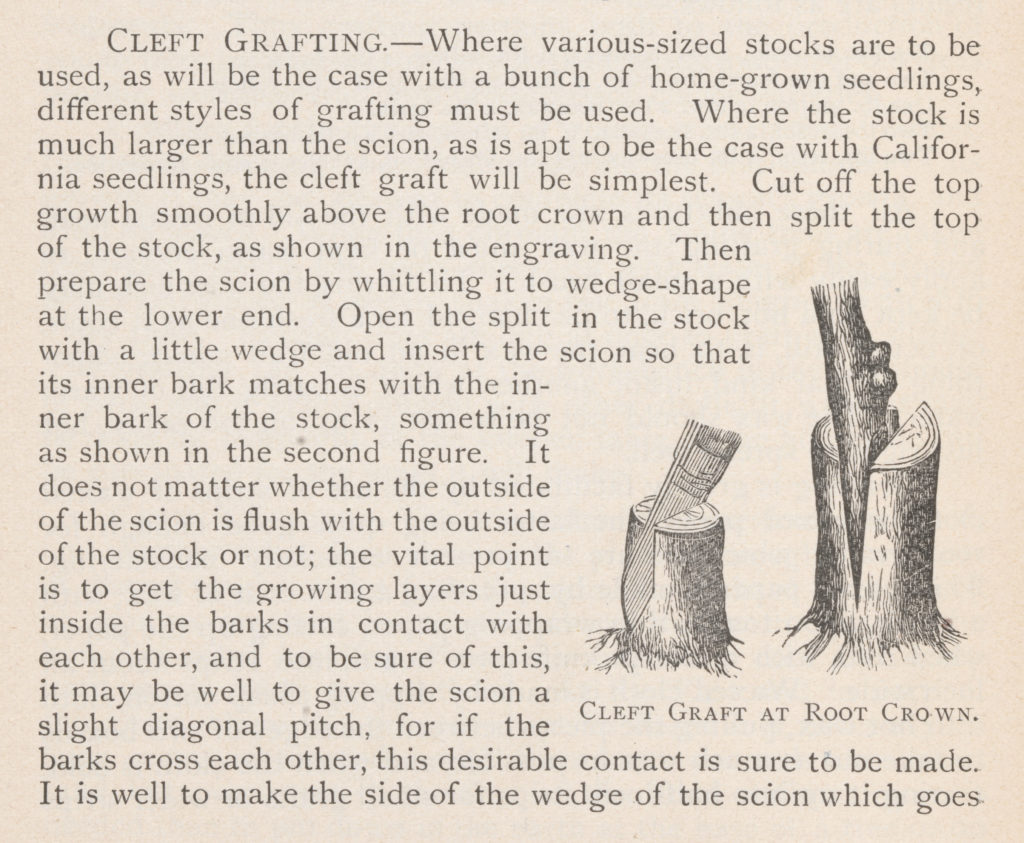

Written by Edward J. Wickson in 1889, The California Fruits and How to Grow Them is a manual that covers nearly every topic a novice California horticulturist would seemingly need to learn to begin cultivating fruit, whether in the late-nineteenth century or today. Wickson’s handbook begins with an overview of California’s climate and soils before moving into descriptions of the range and histories of various wild and introduced plant species, such as the California crabapple, the wild gooseberry, and the California jujube. Those eager to introduce their own varieties of common fruits could find more than enough help in the second half of Wickson’s The California Fruits and How to Grow Them. From recommendations for growing specific plants to guides on how to implement certain cultivation techniques, such furrow irrigation or grafting, an important method for propagating certain species like apple trees, Wickson’s volume contains an array of horticultural tips and tricks to help the aspiring horticulturist to get their backyard orchard up and running.

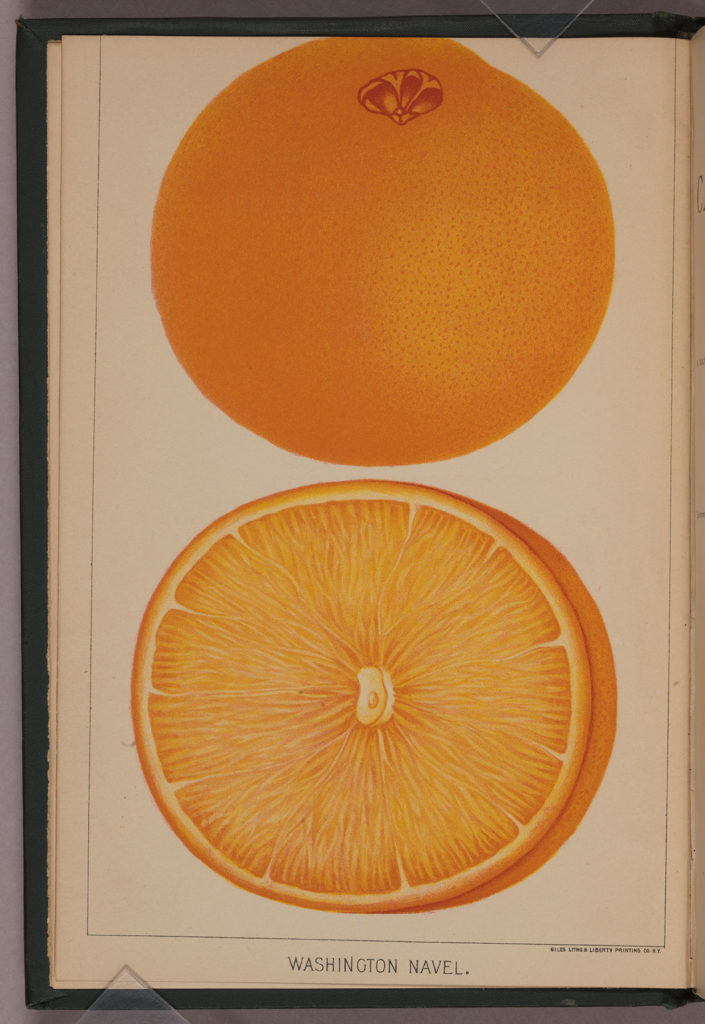

The California Fruits and How to Grow Them, however, is much more than just a horticultural manual. Wickson’s volume, like many others contained in the Edward L. Greene Collection, reveals much about the intersections between science, human-nature relationships, and American identity in the late-nineteenth-century United States. For Wickson’s readers, the scientific knowledge they gleaned from The California Fruits and How to Grow Them rendered history visible in the form of the very fruit they plucked from the California environment. Crabapple trees and evergreen shrubs such as manzanita became reminders of California’s indigenous histories as Wickson informed readers that these fruit-bearers were “highly esteemed by the Indians.” Other fruits conjured images of Spanish California, including “orange, fig, palm, olive and grape,” all of which, according to Wickson, Jesuit priests established at the Spanish missions that spread across the region in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In Wickson’s view, however, “these early efforts at improvement of California fruits were but faint forerunners of the zeal and enterprise which followed the great invasion by gold seekers.” For Wickson, specific techniques typified this pioneer “zeal” and ushered California not only into a new historical period but a new era of fruit cultivation, such as grafting. Grafting is a technique of propagating a variety of fruit by inserting a bud of the chosen variety into the trunk of an existing tree (usually of a different species). Though grafting is an old technique for food production, one likely present in California since at least the Spanish colonial period, Wickson omits this detail in text instead associating grafting with other American technical innovations such as the use of railroad transportation to move fresh fruit in and out of the state. Instead, grafting and railroad transportation embodied the ways in which Wickson imagined Californians as ushering in a new and, by implication, better era of fruit cultivation throughout the state. Deploying nineteenth-century notions of progress and improvement to chart the place of American migrants in California’s natural and human histories, Wickson’s book transformed horticultural practices into metaphors that signified how and why California fit into American history, grafting Wickson, other Californians, and their recent possession of the California landscape onto the fruits of the California environment in the process.

Nineteenth-century Californians like Wickson understood fruit as more than simply a thing to cultivate. Fruit trees, vines, and shrubs were also botanical texts through which Californians could read themselves into the history of the state. Much like the apple orchards, pumpkin patches, or corn mazes many Americans will wander through this fall, orange groves and hillsides covered in gooseberries provided nineteenth-century Californians with experiences that may have helped them to anchor themselves in new places, communities, or environments. Fruit, as Wickson’s volume reveals, was central to being Californian–a thing California is not only known for, but through which people have historically come to know themselves and the state. Perhaps, with our autumn strolls through apple orchards or pumpkin patches, Americans today are not so different? Food for thought, I suppose. Happy fall everyone!

Further reading:

Sackman, Douglas. Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Nash, Linda. Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Ott, Cindy. Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Object. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World. New York: Random House, 2001.

Bolton Valencius, Conevery. The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land. New York: Basic Books, 2002.