by Anne Elise Crafton, PhD, RBSC Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Hesburgh Libraries

National Portrait Gallery, London; Photographs Collection, NPG x12731

Few 19th-century antiquarians matched the obsession of English baronet Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872). A self-described “vello-maniac” (lover of parchment), Phillipps spent his life and fortune amassing what became the largest manuscript collection of his time — over 60,000 manuscripts, plus 20,000 printed works.

Driven by a fear of biblioclasm, Phillipps’ believed he was preserving manuscripts from destruction. This, however, came at a great cost. Life at his estate, Middle Hill, was characterized both by the extreme debts and temper of its master. Phillipps feuded with nearly everyone, including neighbors, tradesmen, tax collectors, scholars, Catholics, curators, his father, wives, daughters, and especially his son-in-law, James Haliwell. Despite near-constant financial ruin, he continued to buy relentlessly, often enlisting his daughters to help catalog and transcribe his acquisitions.

The summer Spotlight Exhibit (running from May through August), Bibliomania: The Library of Sir Thomas Phillipps, features five items from this impressive collection.

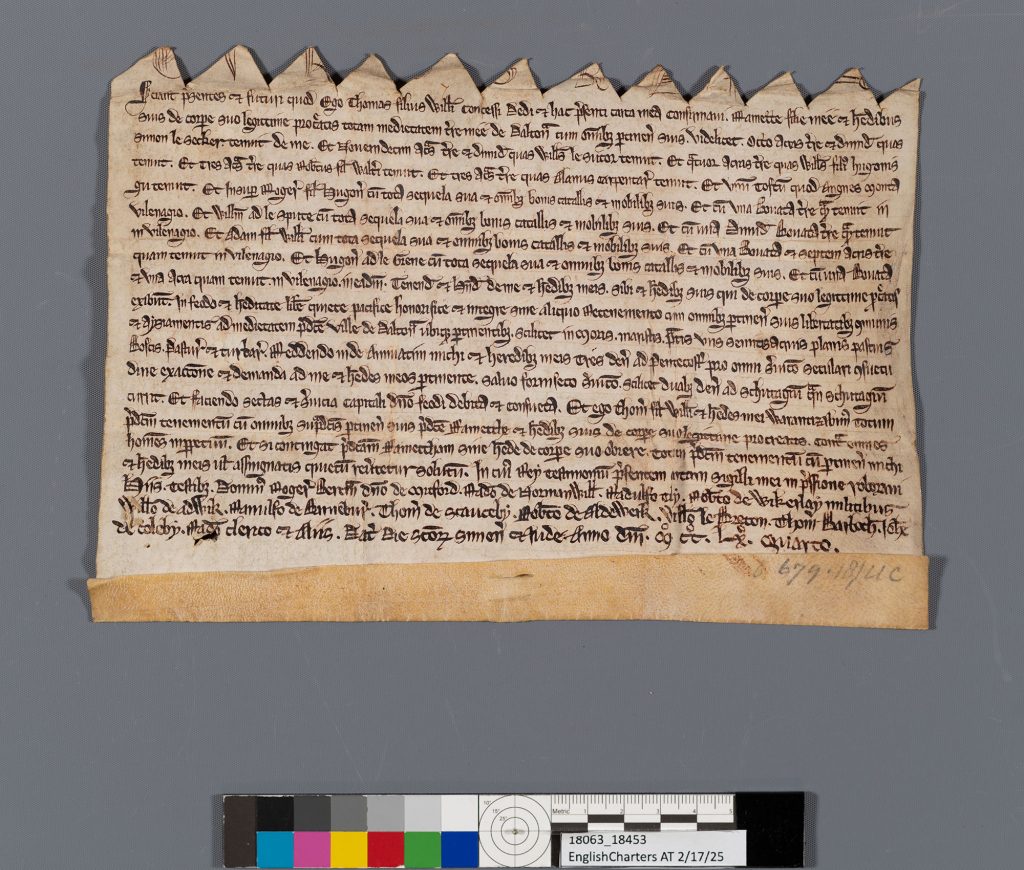

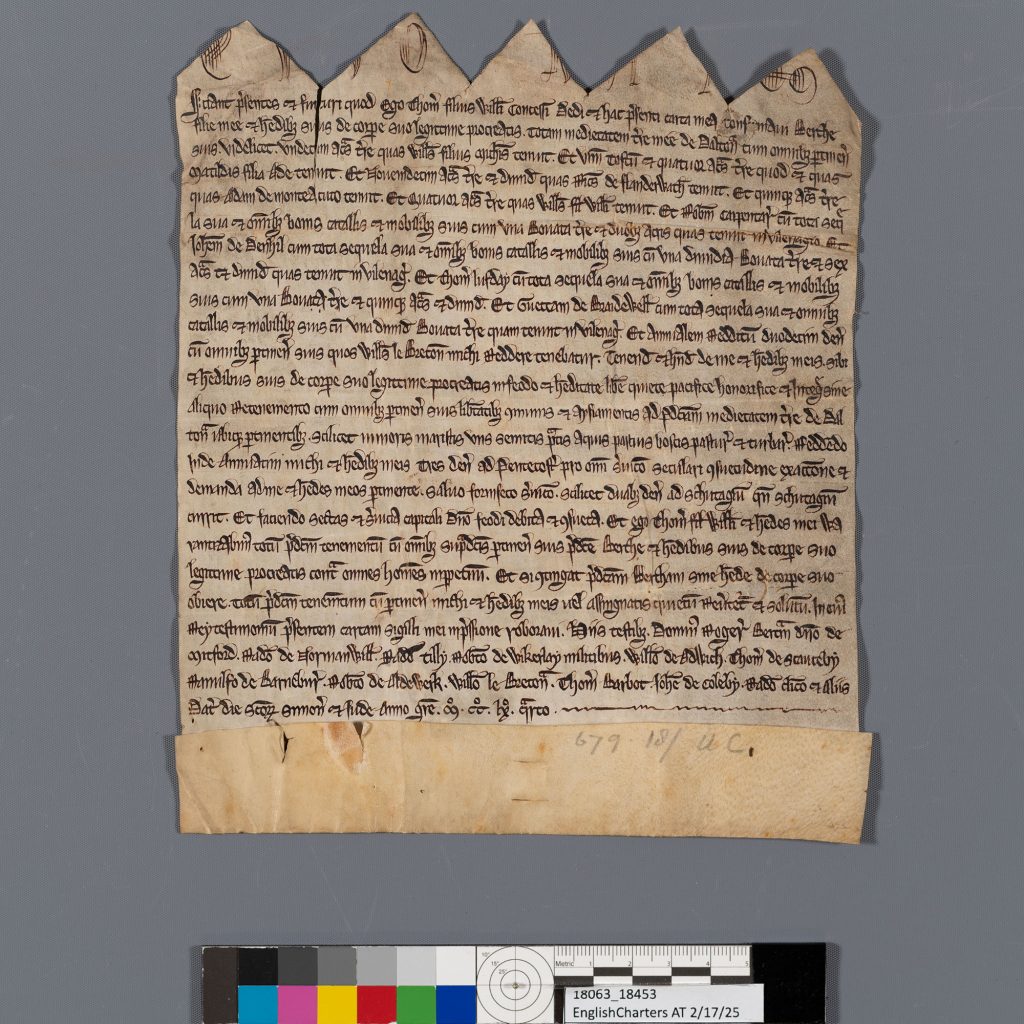

Three of the items in this exhibit are medieval English documents known as “private charters” — that is, records of transactions between private citizens.

According to these documents, Ch_ang_01_12 (above) and Ch_ang_01_13 (below), on October 28, 1264, a man named Thomas conveyed vast tracts of land in Yorkshire to his daughters, Ramette and Berthe.

Despite his vast collection, Phillipps infamously rarely read the items in his library. Indeed, one of the great criticisms levied against the collector was that he simply hoarded manuscripts without the ability or interest to use them. An exception, however, were charters. Driven by a passion for genealogy, Phillipps was known to scour deeds for names and places for use in studies of pedigree, which he published with his own private press.

Yet, notwithstanding this personal interest, thousands of the deeds in his collection went uncatalogued during his lifetime. Only after his death did his grandson, Thomas FitzRoy Fenwick, receive legal permission to organize the collection for sale, at which point over 26,000 items were finally given their iconic Phillipps numbers. To streamline the process, Fenwick often gave the same number to related items, such as Ch_ang_01_12 and Ch_ang_01_13, both catalogued as Phillipps no. 27,951.

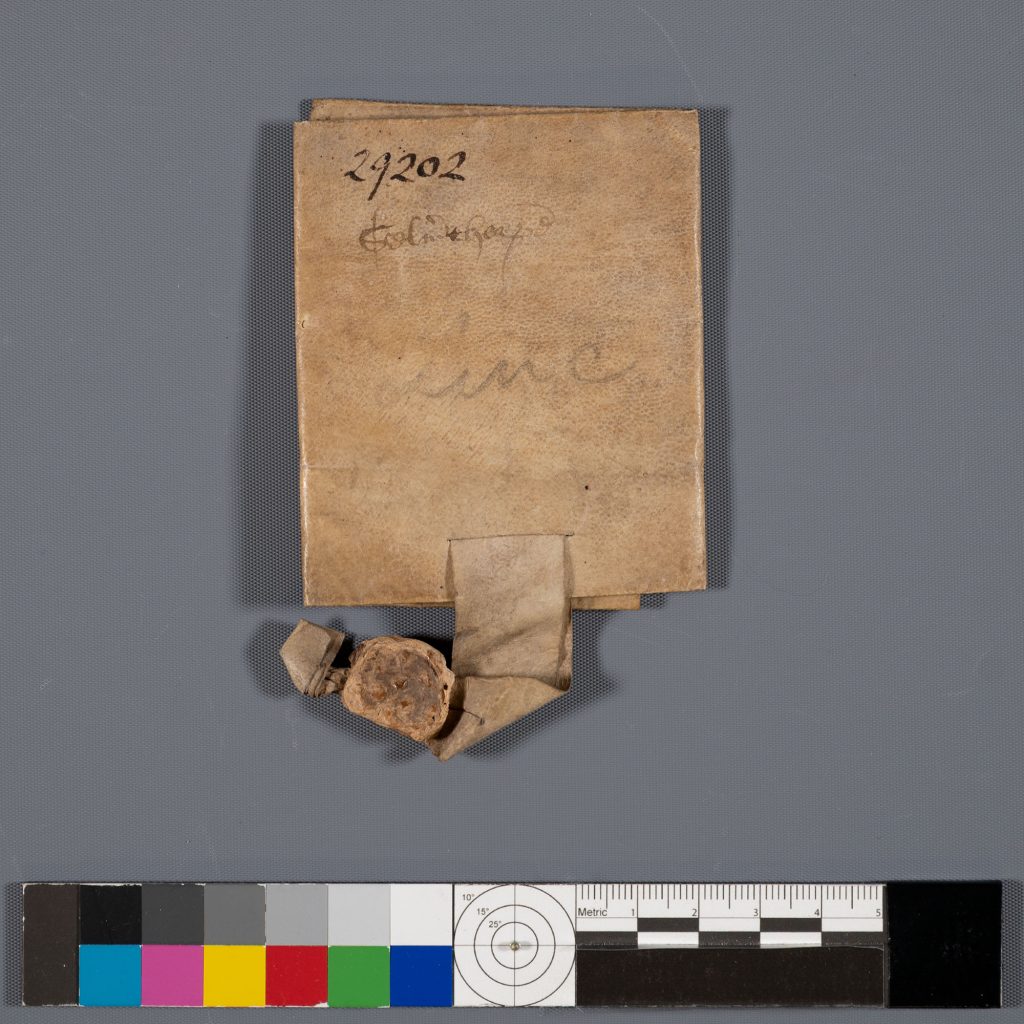

You can see the hand of Thomas FitzRoy Fenwick on the exterior of Ch_ang_01_09, the third charter in this exhibit. Ch_ang_01_09, which records a 14th century transaction between Robert of Cawthorne to Nicholas and Walter del Brom, is in its original “docketed” form — a pre-modern filing system in which documents were folded and labeled. Above the labels of “Scelmthorpe” (Skelmanthorpe, a nearby town) and “Lanc” (perhaps referencing the Lancaster family, lords of Skelmanthorpe), Fenwick wrote the number “29,202.” See the video below for how this charter unfolds!

Although Phillipps often described himself as a “vello-maniac,” he also owned many paper manuscripts. The other two items in this collection — both bound paper codices — tell us even more about the extensive Phillipps collection.

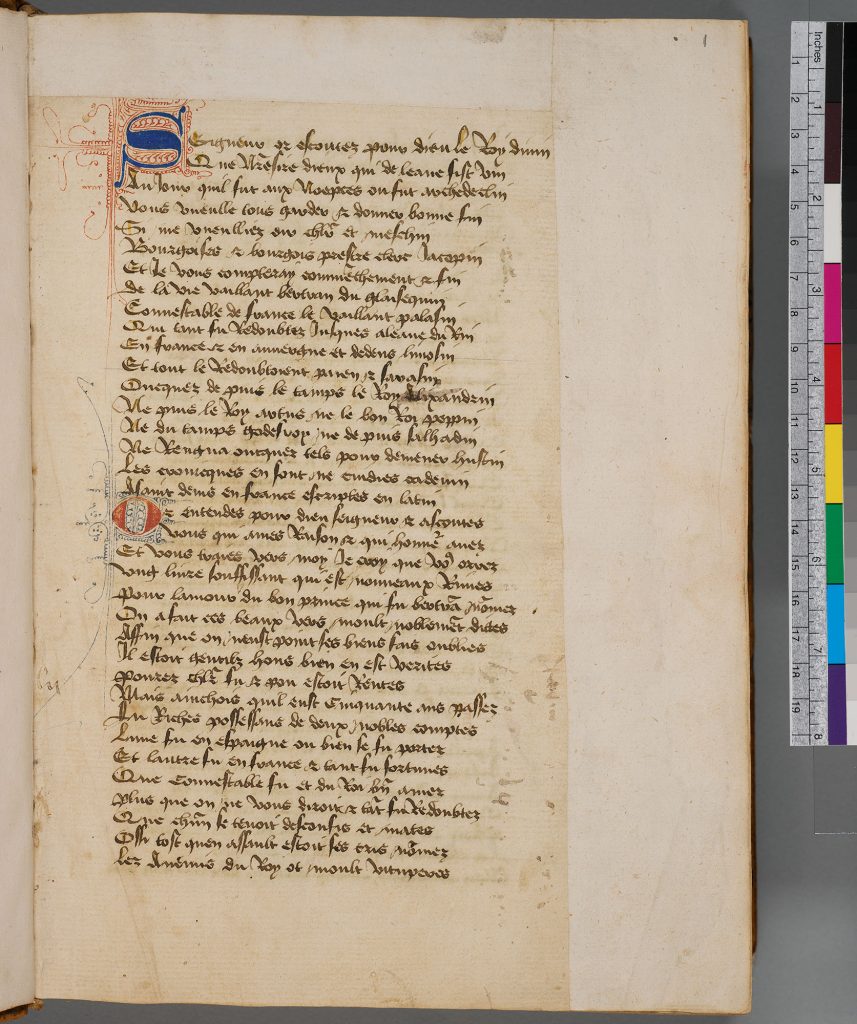

This French manuscript (MS Fr. c. 2) contains the poem “The Song of Bertrand of Guesclin,” one of the last examples of the Old French epic tradition. This Chanson, copied in 1464, tells the story of Breton noble Bertrand, who rose to fame during the Hundred Years War. Phillipps acquired this copy from the library of Richard Heber (d. 1833). Though unable to afford the 1,700 manuscripts in the collection, Phillipps persuaded the auction house to postpone sale until he could amass the appropriate funds, which he finally did in 1836. The shelfmark affixed to the spine, by Phillipps or his daughters, identifies this manuscript as the 8,194th item in his library.

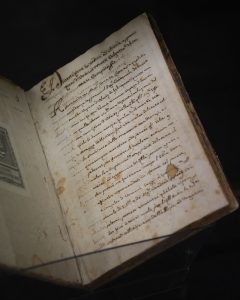

Finally, although you might associate the early modern era with the advent of the printing press, people continued to write the majority of their works by hand for centuries. The final item in this collection is one such manuscript.

In 18th century Europe, vampirism was a hotly debated topic. The concern was so great that in 1739 Pope Clement XII asked Giuseppi Antonio Davanzati to examine the subject. Though skeptical of such creatures, Davanzati’s Dissertazione sopra I Vampiri (MSE/EM 1005-1B) is often credited with introducing the word vampire to the Italian language.

In his first catalogue of his library, Phillipps claimed to have acquired this copy of the Dissertazione (Phillipps no. 5,485) in 1830, when he purchased 1,560 items from the library of Frederick North, 5th Earl of Guilford (d. 1827). The manuscript does not appear in the original catalogue of the Guilford sale (Phillipps claims it was included informally), and so we must take him at his word.

Upon his death, Phillipps’ will mandated that his collection never be separated, nor that any Catholic ever be permitted to view the collection. These wishes proved untenable, and over the next century, his vast library was slowly dispersed. Today, as this exhibit attests, fragments of his hoard reside in institutions worldwide — including the Hesburgh Library.

After earning a Ph.D. in Medieval Studies at the University of Notre Dame, Anne Crafton undertook a postdoctoral fellowship in the Hesburgh Libraries’ Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC), where she spent a year cataloging a diverse collection of previously undocumented materials. The opportunity was made possible through the College of Arts & Letters’ 5+1 postdoctoral fellowship program, which offers a postdoctoral fellowship to any student who finishes and submits their dissertation in five years.