If you’ve ever turned on Discovery channel during Shark Week, then you’ve probably seen the iconic footage of a 2.5-ton great white shark leaping out of the water to catch its next meal. If you’re weird like me and you’ve ever tried to mimic one of these epic breaches in a backyard pool, then you realize just how difficult it is to generate enough momentum to jump even partway out of the water and therefore have a real appreciation for what it takes to pull off this incredible feat.

So if a breach attack is so difficult to pull off, how are great white sharks able do it, and why do they do it? As per usual, some basic physics can help us answer both these questions.

According to a 2011 paper by Martin and Hammerschlag, who spent 13 years studying great white predation in South Africa, breach attacks allow great whites to play to their strengths and maximize stealth.

Millennia of evolution have left great whites with long bodies great for straight-line speed (can reach speeds >11m/s) but not so great for agility. Additionally, roughly 95% of a great white’s muscle is white muscle, which allows for rapid contraction (e.g. speed bursts) but also results in poor endurance. Considering these aspects of their physiological makeup, it’s in a great white’s best interest to attack swiftly, avoiding prolonged chases. Martin and Hammerschlag report that the majority of great white attacks on seals are over within 2 minutes and that the longer an attack drags on, the less likely it is to be successful.

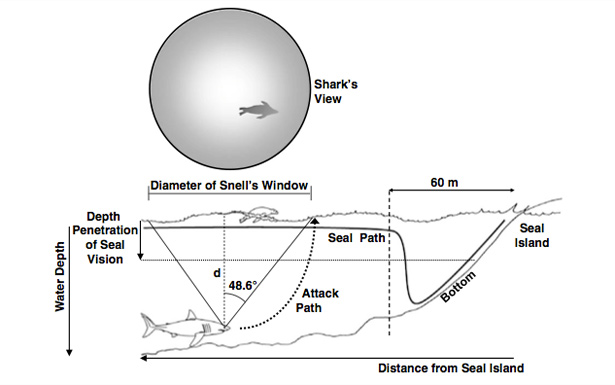

As great whites are less agile than seals, maximizing stealth and minimizing the time seals have to react is imperative. Having evolved to have a dark grey dorsal (top) surface, great whites are hard to distinguish from the coral on the ocean floor when viewed from above (seal’s perspective). Additionally, since very little of the light entering the water is reflected back towards the surface, it is estimated that under even the best lighting conditions, a seal could only reliably distinguish a shark a maximum distance of roughly 5m below it, which explains why great whites attack from below rather than behind. Great whites need about 4m to reach top speed, so due to this acceleration distance and seal vision, Martin and Hammerschlag report that great white attacks generally start between 7m and 31m below the ocean surface, with the majority staring closer to 30m. Looking at data for great white breach attacks ranging from vertical to 45 degree ascents, Martin and Hammerschlag estimate that it typically takes a shark between 2 and 2.5 seconds to go from initial acceleration to surface breach, and that when considering shark speed and average visibility conditions, a seal generally has only about 0.1 seconds to react if it spots the shark before contact is made. Ultimately, due to the advantages it gives them, great whites are successful in over half their breach attacks when lighting conditions are ideal.

Sources & Further Reading:

Featured image by Alex Steyn under Unsplash License