In the present day, it can seem as though nearly every young person wants to be muscular. Phrases such as “winter arc” or “the bulk” are frequently used on social media platforms to describe people changing their physique through weight training. With this resurgent fitness craze, it is evident that there are many gym-goers who are actively looking for ways to maximize muscular growth gains. Researchers have recently discovered that one unconventional method for making those gains is through static stretching.

Read more: Is Static Stretching the Key to Muscular Gains?Static Stretching Explained

Static stretching, which entails maintaining a stationary position where a muscle is at full extension, has often been a topic of discussion in weightlifting communities in years past. There have been many unsettled debates on whether or not stretching techniques can improve strength performance and muscle size. In recent years, however, new studies have been conducted which may point towards the potentially massive benefits of static stretching for muscle growth.

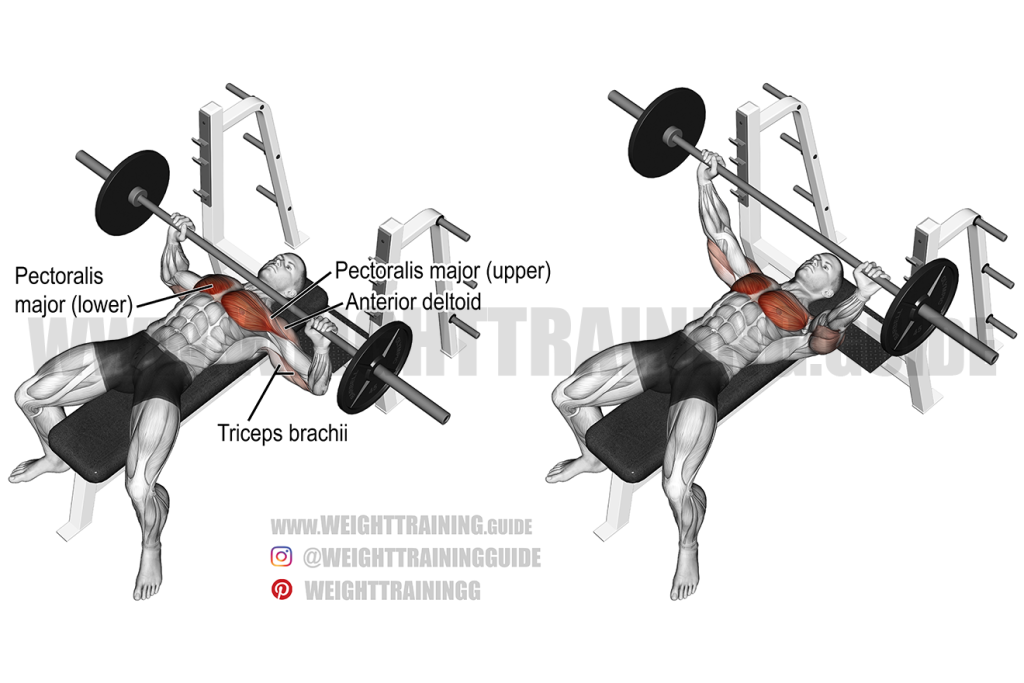

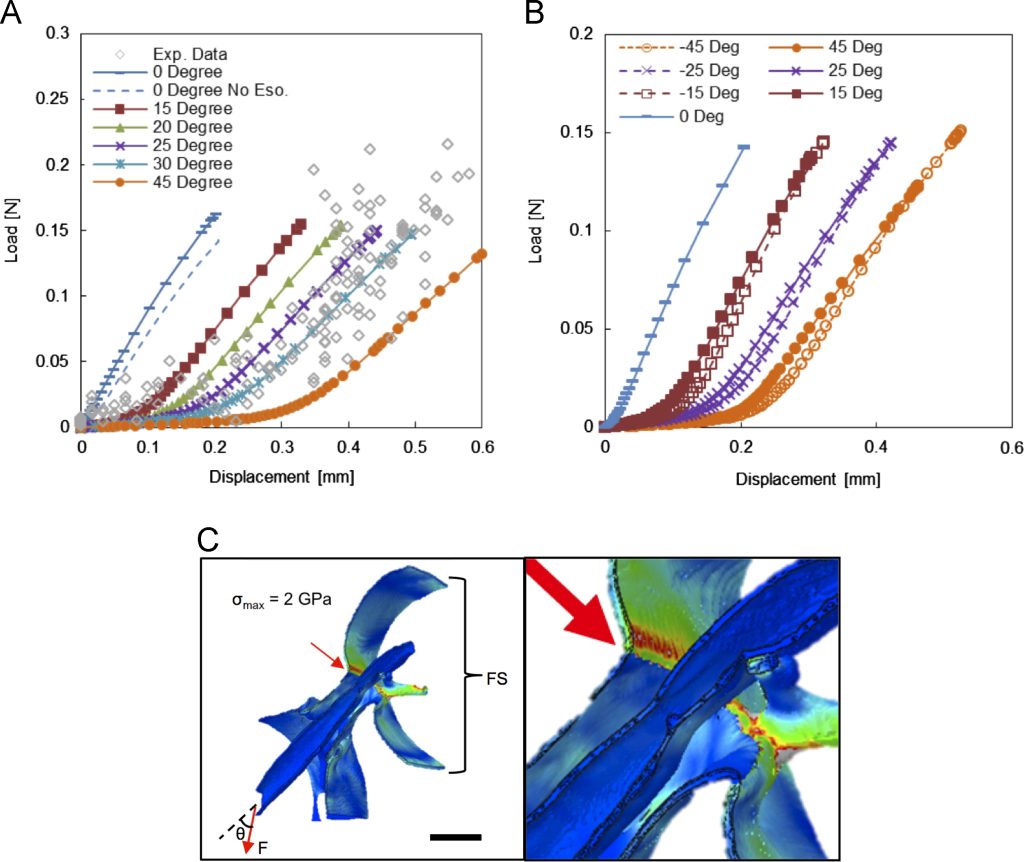

The current understanding is that static stretching induces mechanical stresses, primarily tension, on the muscles of the body. If performed for a long enough duration, this induced stress can lead to muscle hypertrophy. During hypertrophy, the organelles inside of muscle fibers, called myofibrils, which are made up of actin and myosin proteins surrounded by a gel like substance called sarcoplasm, experience some damaging and deformation. In the reconstruction process, new proteins are then generated through muscle protein synthesis, which causes the myofibrils to become thicker and denser, ultimately leading to increased strength. Thus, to achieve any significant muscle growth, hypertrophy must be reached.

First Human Testing

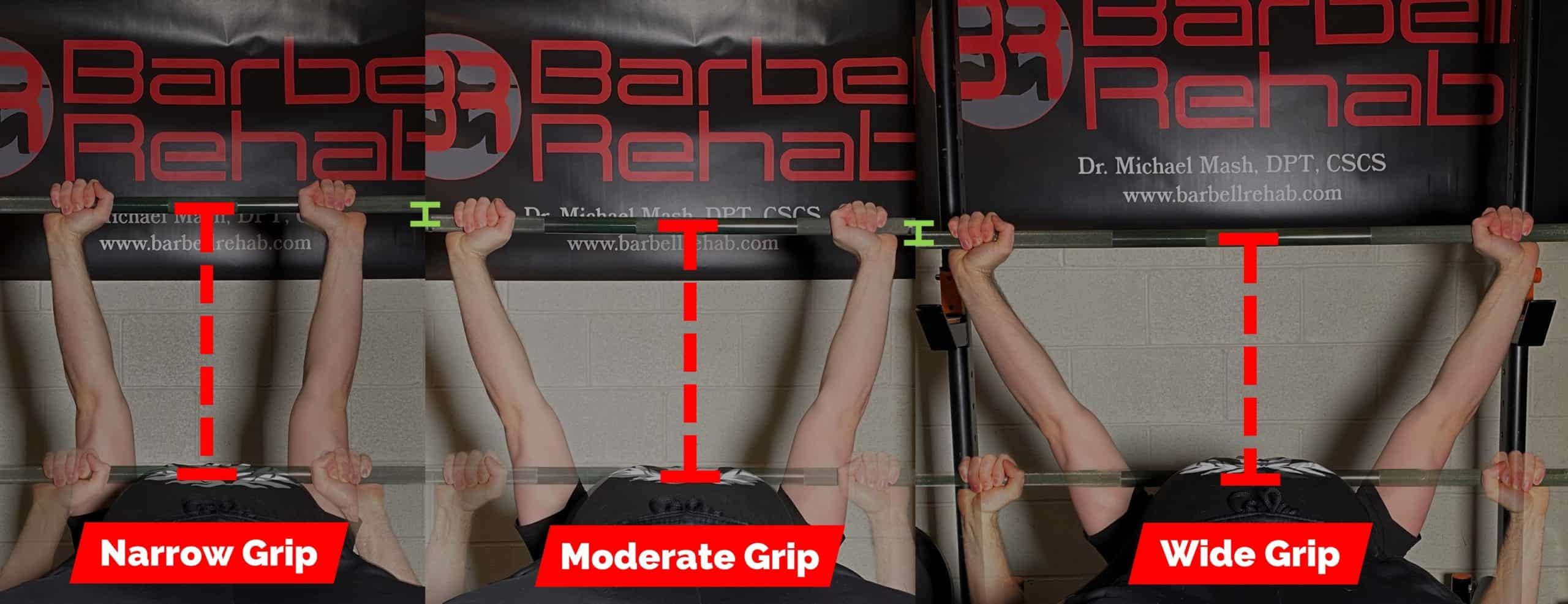

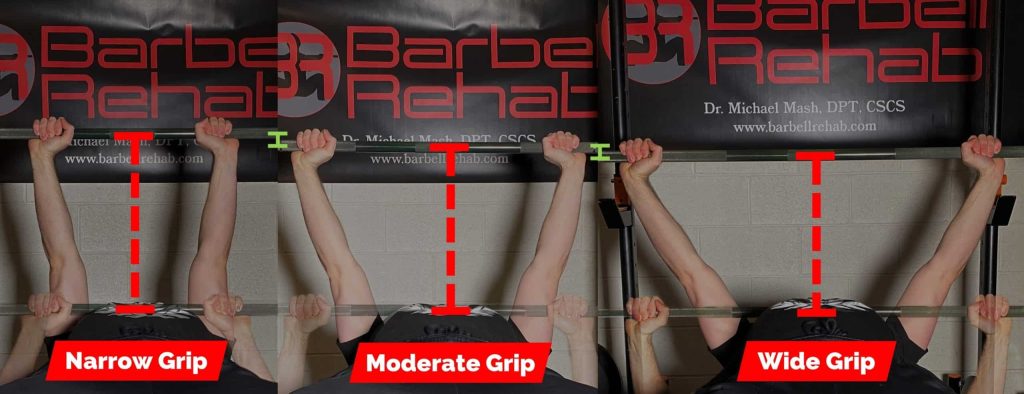

Multiple studies within the last two years have demonstrated that prolonged static stretching in humans can lead to similar levels of muscle hypertrophy in comparison to traditional weight lifting methods. One such study conducted by Wohlann et al. concluded that multiple fifteen minute stretching sessions focused on the pectoral muscles had a nearly equivalent increase in muscle strength when compared to performing traditional weighted exercises concentrated on the same muscles. Another study, by Warneke et al. obtained similar results with the plantar flexors, although in this case the static stretch was held for one hour every day. These findings indicate that regardless of the mechanism or method for creating stress, as long as muscle fibers are kept in constant tension there can be hypertrophy and thereby growth.

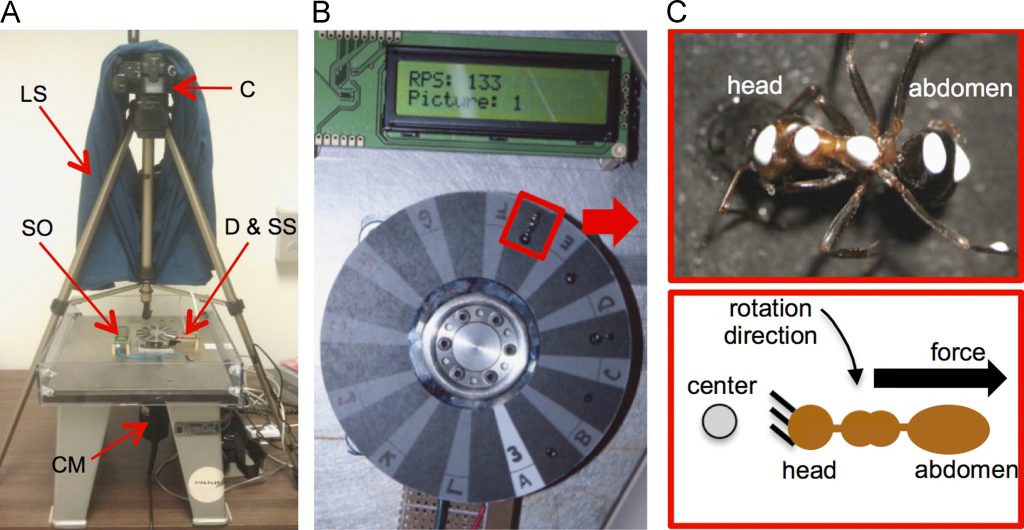

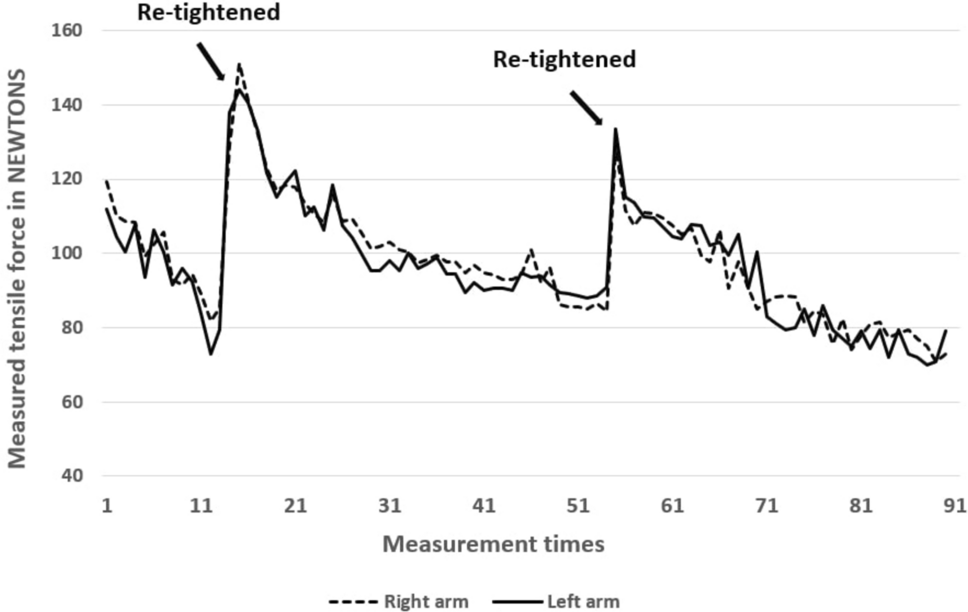

To achieve constant stress, the studies mentioned utilized external loads and re-adjusted positioning. Study participants would strap into simple devices which allowed for continual tightening as their muscles loosened over time after being initially stretched. Although uncomfortable to maintain, this constant stress is crucial for breaking down the myosin proteins. Only after the proteins are broken down mechanically does the body generate an inflammatory response which signals to begin the repairing process.

Current Applications

Although the practicality of static stretching as a primary means of achieving muscle growth still remains in question, there is no doubt that the potential benefits of stretching are much greater than sole flexibility. These findings grant deeper insights into the large role tension plays in muscle growth which can be taken and applied to weight training. As more research is conducted, it is highly possible that the answer to the long-asked question of how to achieve maximum hypertrophy may involve some combination of traditional weight lifting techniques and more novel static stretching holds.

Additional Reading:

Feature photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels.