Who wouldn’t want to look like Captain America? This common desire to attain a strong Herculean physique, either for athletics or aesthetics, has led many ambitious men and women to weightlifting. An egotistical motivation puts these people at risk of injury, however, as they sacrifice proper form to achieve their next personal best. The bench press is one example of an effective but potentially dangerous lift.

This upper body exercise requires an individual to lie flat on a bench while repeatedly lowering and pressing a straight bar loaded with weights on each end. The hands evenly grip the bar slightly wider than shoulder width apart with the feet remaining flat on the ground and the arms fully extended. During the eccentric (or lowering) phase, the bar is brought in contact with the lower chest. The bar is then pressed up until the arms are once again fully extended (concentric phase).

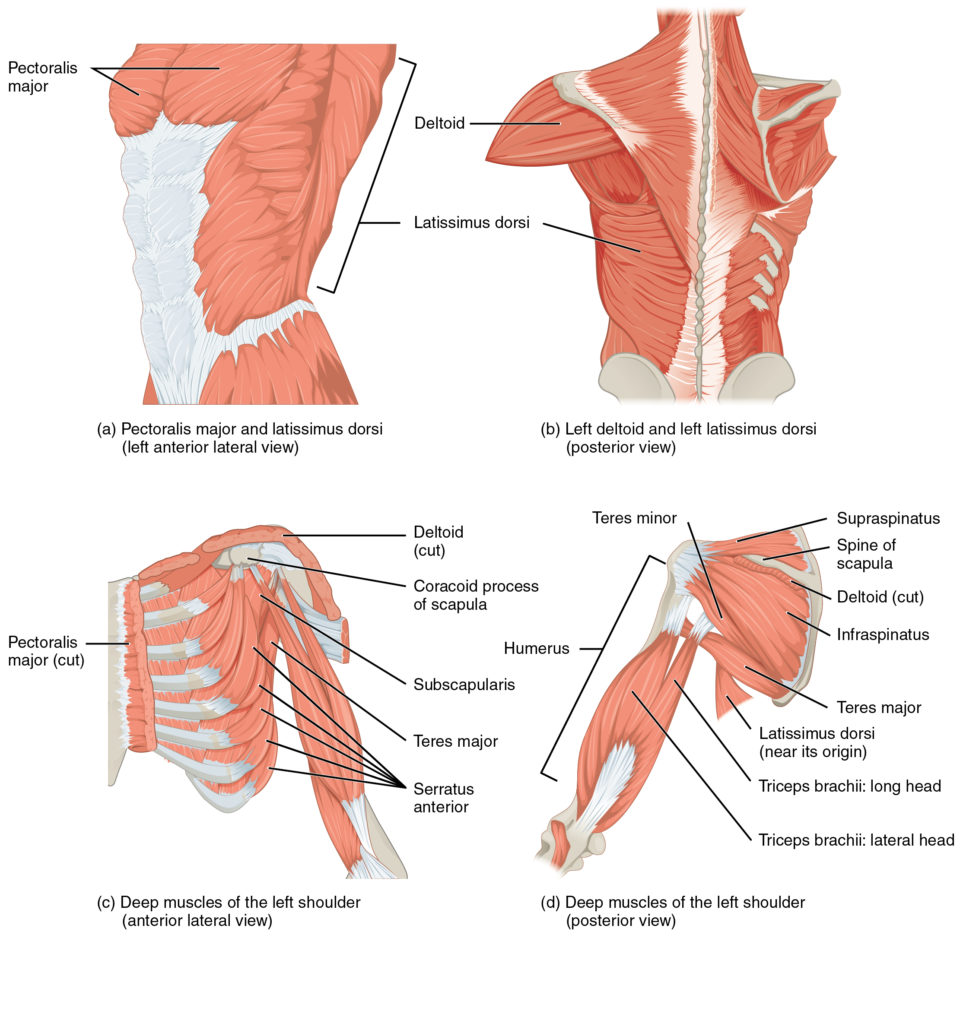

Recreational weightlifters commonly use a wider grip on the bar, believing that this will increase activation of the chest muscles and allow them to mimic Terry Crew’s version of the Old Spice Man. One study performed on 12 powerlifters, however, found that the prominent muscles used during the lift, such as the pectoralis major, triceps brachii, and anterior deltoids (i.e. chest, triceps, and shoulders), experienced similar electromyographic activity despite varying hand spacing.

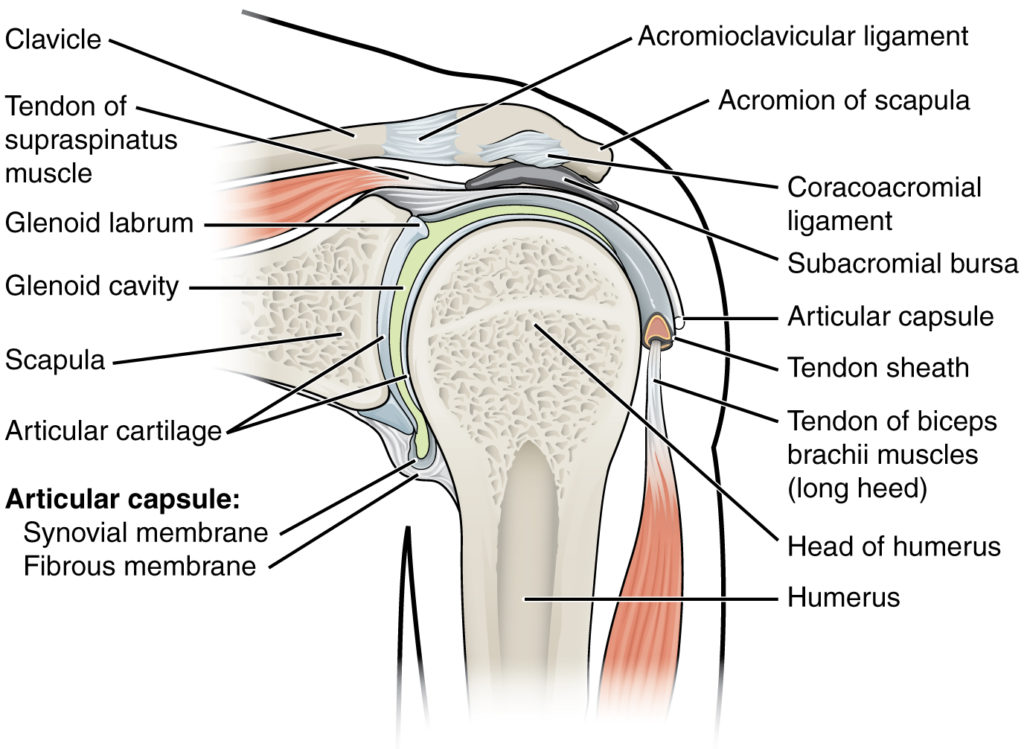

Although hand spacing does not significantly affect muscular activity, it can lead to injury. A review of several studies on the effects of hand grip found that a grip width greater than 1.5 times biacromial width, or shoulder width, naturally resulted in shoulder abduction, or rotation away from the body’s centerline, greater than 45°. As this angle increases, shoulder torque increases, causing potential injuries. For instance, the inferior glenohumeral ligament, a ligament restricting translational motion in the anterior direction at the shoulder’s ball and socket joint, may tear as abduction increases, causing instability at that joint. Repetitive cycles with this wider grip may also cause acromioclavicular joint (AC Joint) osteolysis – chronic destruction of the bone tissue at the joint between the clavicle and acromion.

Aside from a wide grip, injuries also commonly stem from over-training and using excessive weight. Research on 18 male college students demonstrated that repeating the bench press motion with high frequency until failure resulted in a significant increase in the medial and lateral force exerted on the elbow joint, which could result in injury over time. Furthermore, performing the bench press with heavier loads could result in a sudden rupture of the pectoralis major. At the bottom of the eccentric phase as the bar touches the chest, the muscle fibers are simultaneously lengthening while also contracting, which increases the risk of muscle tear in this region.

Unlike Captain America, people cannot instantly acquire strength or build muscle. Muscular development and improving one’s bench press require time, patience, and proper form. To learn more about injury prevention or variations of the bench press, check out the video below or read these papers by Bruce Algra and JM Muyor.

Featured image titled “Bench press yellow” which is licensed under CC BY 2.0.