Every 25 seconds, someone is killed in a car accident, resulting in more than 1.25 million deaths worldwide each year.

As a result, dummies are an important tool used in many safety tests for car crashes, and they help to inform many design decisions for automobile manufacturers. Since these dummies are used to assess human behavior in many types of situations involving collisions, swerving, and other performance measures, the primary goal for dummy creators is to imitate human response as closely as possible using artificial means.

Read more: Wreckage Before the Real Crash: The Biomechanics of Crash Test DummiesTherefore, biomechanics plays an integral role in dummy design, from choosing materials that accurately reflect limb stiffness, to assembling ball-and-socket joints that sever when undergoing a certain threshold stress or strain. There are many techniques that researchers use – from computational models to in-field testing – to ensure these dummies reflect the parameters and properly inform the design decisions they are a part of.

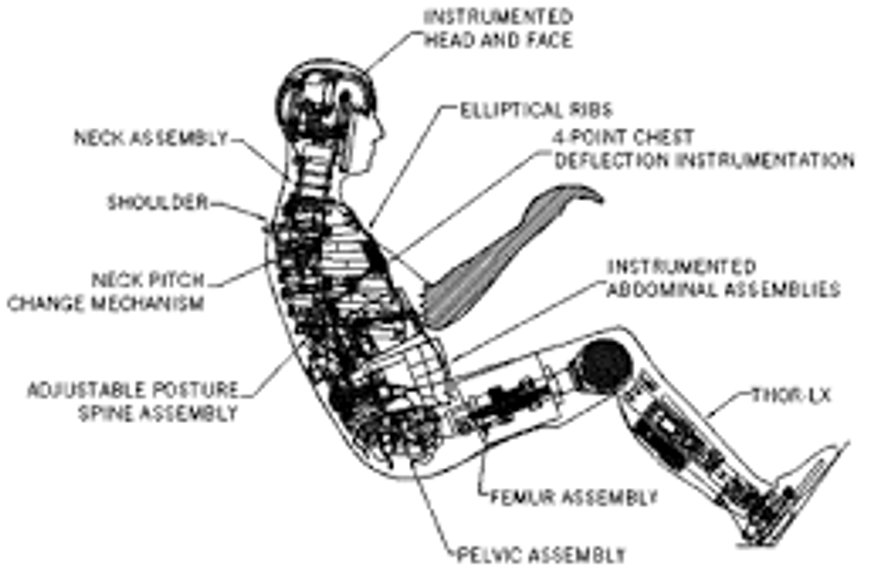

Manufacturers routinely spend millions of dollars each year to develop and fine-tune the dummies (or more technically known as anthropomorphic test devices or ATDs) that they implement in their testing procedures. Its history can be traced all the way back to 1949, where the US Air force implemented a dummy for test ejection seats, while they were first implemented commercially by General Motors more than 30 years later. They have undergone many advancements in terms of their accuracy and manufacturing efficiency, arriving at the now ubiquitous Hybrid-III model, which resembles a 50th percentile adult “family man” male that is used in almost all testing simulations. Although many cadever models have been explored, these artificial models offer the most consistent and reliable solution to testing needs, which involves blunt head-on crashes, various types of rollovers, and other rear-based and side-based collisions. By equipping dummies with different kinds of sensors, primarily consisting of MEMs accelerometers and other force transducers, dummies provide predictive power on the impact of different simulation parameters on driver safety and other outcomes.

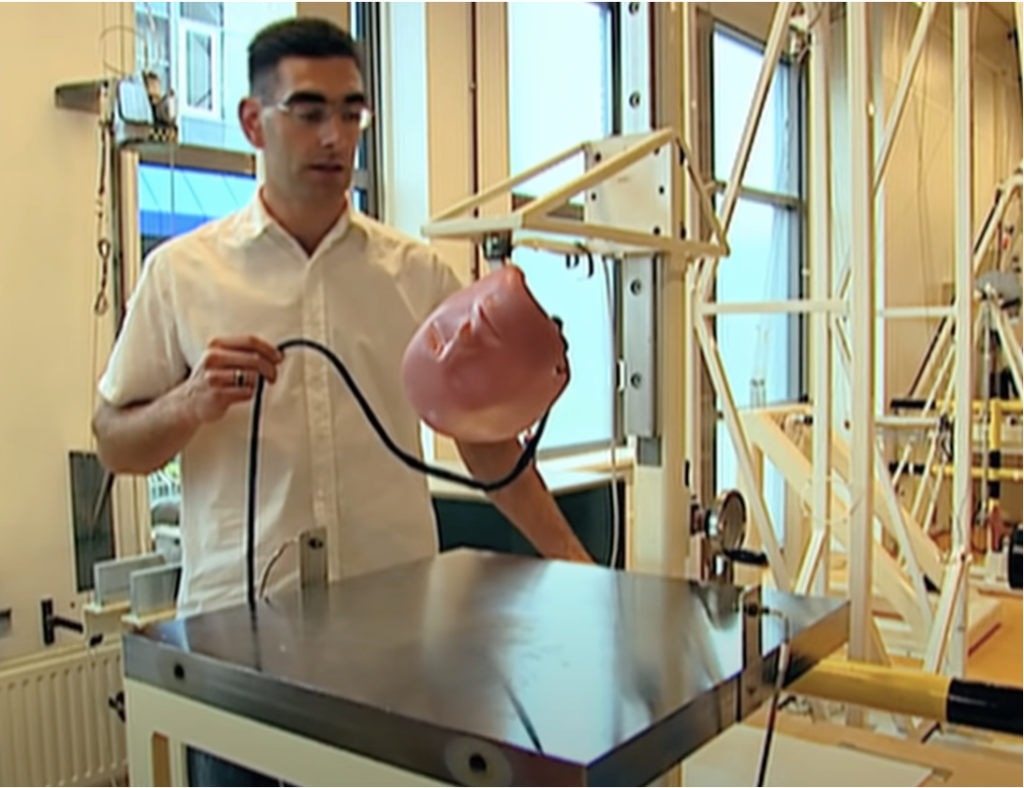

Dummy performance analysis can be found both in creation of the dummies, ensuring the dummies have the correct human mechanical properties, and in dummy testing, anticipating damages in crashes. Both see a heavy cross-section in biology and mechanics, best illustrated by the head-drop test in the initial development stage. Here, a dummy head undergoes a drop from a predetermined height, and sensing systems ensure the model has optimal weight and damping properties in comparison to in vivo concussion testing. This way, when the commonly used QMA Series 3 DoF Force Transducer later measures neck whiplash force (the most common cause of car crash injury), testing models can be confident such data will reflect real-world collisions. These kinds of before and after tests are used in all parts of the dummy, from parts as large as the lower back, to parts as small as the hinge joint in a finger knuckle. Such precision is needed in all areas to increase the predictive power of dummies, since details like Young’s Modulus (a measure of stiffness) in the chest area affects steering wheel impact displacement, while the coating paint consistency affects the skin abrasions associated with friction and rubbing. Each part of the dummy is crafted meticulously, and as such, the manufacturing and design process of the dummies involves a fast knowledge of physics, biology, and everything in between. Some additional overviews and readings can be found here and here.