Can you imagine a world where amputees receive replacement limbs which are able to detect temperature and pressure like an actual limb? How about a world where when you get a cut, you can 3D print some of your own skin to patch the wound?

To the average citizen, this might seem like something out of a science fiction movie. To researchers at the Graz University of Technology, the Wake Forest School of Medicine, and the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, this is a reality that they are helping bring ever closer. Both of these scenarios are discussed in a recent article by Mark Crawford, who investigated the recent breakthroughs in 3D printing human skin and creating sense-sensitive artificial skin.

At the Graz University of Technology, researchers are working on creating an artificial skin that can sense temperature, humidity, and pressure. Currently, artificial skins can measure one sense at best, but with the use of the nanoscale sensors that these researchers are developing, sensing all three at once could be possible. This is achieved through the materials that the nanosensors are created out of: a smart polymer core and a piezoelectric shell. The smart polymer core can detect humidity and temperature through expansion, and the piezoelectric shell detects pressure through an electric signal that is created when pressure is applied. With this technology, prosthetics could be made which could allow the wearer to retain some of their lost senses.

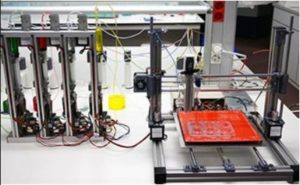

At the Wake Forest School of Medicine, researchers have created a handheld 3D printer which produces human skin. This device could be used to replace skin grafts, as it can apply layers of skin directly onto the wound. Through the use of bioink, this handheld printer can create different types of skin cells. After scanning the wound to see what layers of tissue have been disrupted, it can print the appropriate skin needed to correct the injury.

At the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, researchers are also 3D printing human skin using bioink. They are creating both allogenic and autologous skin to create the optimal skin, which is a combination of the patient’s own cells and cells created from a stock. Although they have managed to print functioning skin in its natural layered state, it is tricky to create the cells in such a way that they do not deteriorate.

It is also tricky to correctly deposit the product. To illustrate, more research needs to be done on the mechanical properties of artificial skin before it could be used on humans. The artificial skin must be able to stretch and react to tension in a similar manner to the real skin it will be connected to. Additionally, researchers must figure out how to safely send the signals the artificial skin is detecting to the brain.

Overall, both advancing artificial skins and 3D printing human skins could largely impact humanity. Even though we have yet to use these skins on people, they are already being used in industries, such as L’Oreal, to limit testing on humans and animals. Already, these skins are being used on robots, as seen in this video, to help prepare the skin for human transplant:

Interested in seeing more? Check out some more articles on the advancement of artificial skin from Caltech and Time.

Featured image by Alex Wong under Unsplash License