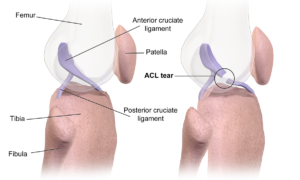

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are among the most common in sports, with nearly 100,000 tears annually. Additionally, the rate of pediatric tears has been increasing at a rate of 2.3% each year for the past 20 years. The high incidence of this injury is in part due to the structure of the knee complex, where the ACL is located. The ACL helps connect the two longest bones in the body and is responsible for rotation and transferring body weight to the ankle. Specifically, the primary functions of the ACL are to prevent the tibia from sliding too far in front of the femur and to provide rotational stability to the joint. This rotational motion, combined with a lack of muscle support at the knee, is why so many athletes tear their ACL. A recent paper looked into how a team of doctors led by Dr. Martha Murray at Boston Children’s Hospital have come up with a promising new approach to repairing the injured ligament.

Due to its environment, ACLs do not repair on their own like other ligaments do. The synovial fluid, which resides in the knee complex to reduce friction in the joint, limits blood flow to the ACL and PCL (posterior cruciate ligament). When injuries occur to these ligaments, the lack of blood flow prevents clotting. In most other ligaments, clotting would occur and would function as a “bridge” for the two ends of the torn ligament to grow and heal across. Due to ACLs not being able to undergo this process, the current method for repair is to take a graft from the patient’s hamstring or patella and replace the torn ACL with the new graft. While this method is typically successful, Dr. Murray’s team estimates that the re-tear rate is about 20% and up to 80% of patients develop arthritis in their knee 15-20 years after the surgery. To combat this, Dr. Murray drew inspiration from how other ligaments heal and developed Bridge Enhanced ACL Repair (BEAR). The premise of this technology is to take a “sponge” that is composed of proteins that are naturally found in the ACL, and insert it between the torn ends of the ACL. Using sutures, the sponge is moved into position and the two ends of the ACL are pulled into the sponge. Blood is then drawn from the patient and inserted into the sponge. This environment acts as a blood clot and stimulates the ACL to repair itself. Clinical trials have shown that the sponge resorbs completely after 8 weeks, at which point the two ends of the torn ACL have begun to join back together. While the BEAR treatment is still relatively new, early results are encouraging with patients seeing similar results to patients that undergo traditional ACL reconstruction. Though it is difficult to predict the rate at which patients who receive BEAR treatment will develop arthritis, animal testing has shown lower instances of osteoarthritis development, which is promising news for those who suffer from this common injury.

For more information about the BEAR technology check out Boston Children’s Hospital website or this recent article. A short video detailing the technology can also be seen below.

Featured image by Eagle Media Pro on Unsplash