The allure of athletic success is hard to ignore in today’s society. The opportunities, notoriety, and wealth that come along with prowess in a particular sport are certainly enticing and have contributed to a growing trend towards youth sports specialization, where athletes focus on one sport from a very young age. And while the work ethic of these young athletes is admirable, their reasoning and that of their parents is a bit flawed.

The data is clear — early sports specialization puts young athletes at a far greater risk for injury, significantly reducing their chances of getting to the next level. One study of more than 1000 young athletes found that highly specialized athletes had a 225% greater risk of serious overuse injury than their non-specialized counterparts. But why exactly does specialization lead to more injuries? Biomechanics certainly has something to say about it.

Muscle Imbalances

Put simply, playing one sport contributes to the development of muscle groups in certain areas of the body and not in others. This should make sense on a basic level – performing the same set of actions repetitively builds strength in the muscles used for that particular sport, while other muscles may be neglected. Given that certain muscle groups play very specific roles in either preventing or causing injury, this phenomenon poses a serious risk.

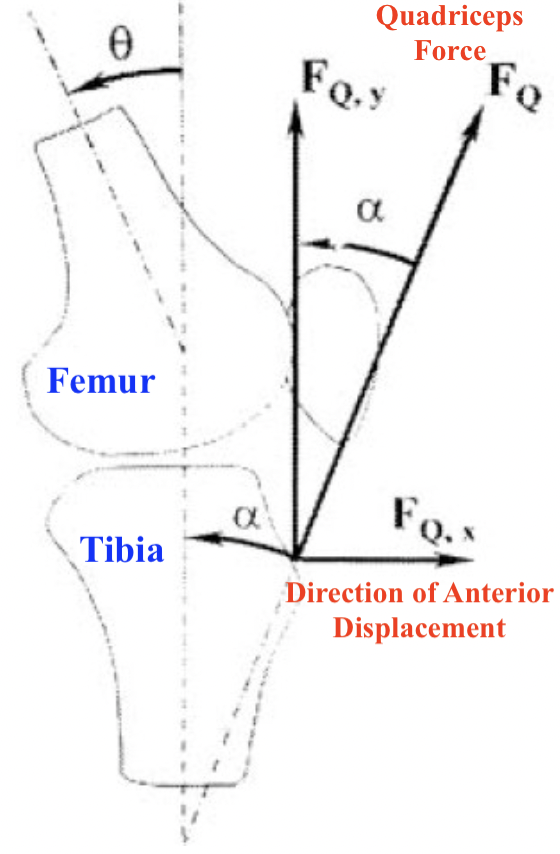

Research has shown, for example, that the quadriceps and the hamstring muscles play completely different roles in the prevention or causation of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. A study by Demorat et al. showed that aggressive loading of the quadriceps results in greater ACL injury risk. The investigators in the study applied a 4500 N load (for reference, the average human can produce a maximum of 3000 N) to the quadriceps of 11 cadaveric legs and found that the average anterior displacement, the amount that the tibia moves relative to the femur, was characteristic of ACL damage. Additionally, the researchers found that in 6 of the 11 legs, the ACL had actually been torn/injured after the quadriceps loading.

On the other hand, More et al. performed a similar in vivo study but found that hamstring loading actually reduces the anterior displacement in the knee, which in turn reduces the risk of ACL injury. Thus, a young athlete whose single-sport training has contributed to the development of strong quadriceps muscles and weaker hamstring muscles is at greater risk for ACL injury, and this is just one example.

Important Properties of Tendons and Ligaments

The injury risks associated with early sports specialization are also attributable to the mechanical characteristics of tendons and ligaments within biological systems. For instance, Woo et al. demonstrated that the extensor tendons of pigs who had been through a year-long exercise program were stronger than those of a control group. More specifically, straining a tendon by a particular amount required more applied force for the exercised group than it did for the control group. This implies that a specialized athlete’s “unexercised” tendons – those not used regularly when performing actions typical of a particular sport – are weaker and may experience damage when the athlete performs awkward or atypical movements.

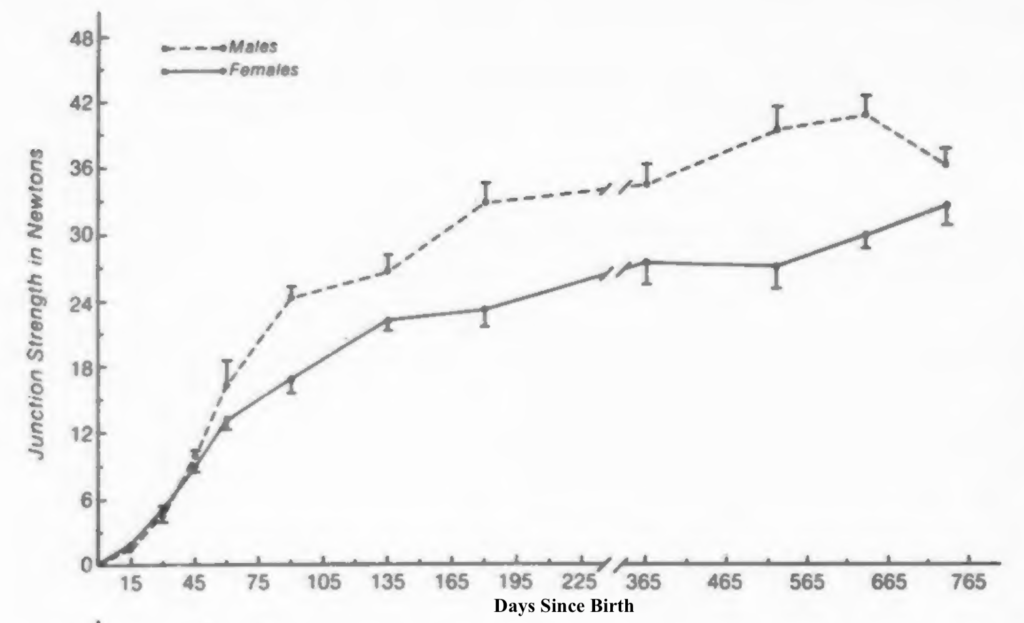

Additionally, age dramatically impacts the mechanical properties of biological tissues. A study by Tipton et al. showed that the bone-ligament knee junction strength of rats increases significantly in the period after a rat is born and as it develops. Though intuitive, this pattern implies that young athletes are at greater risk of injury given that their biological tissues have yet to fully develop.

Ultimately, from a biomechanical perspective, sports specialization seems outright dangerous for young athletes and their parents.