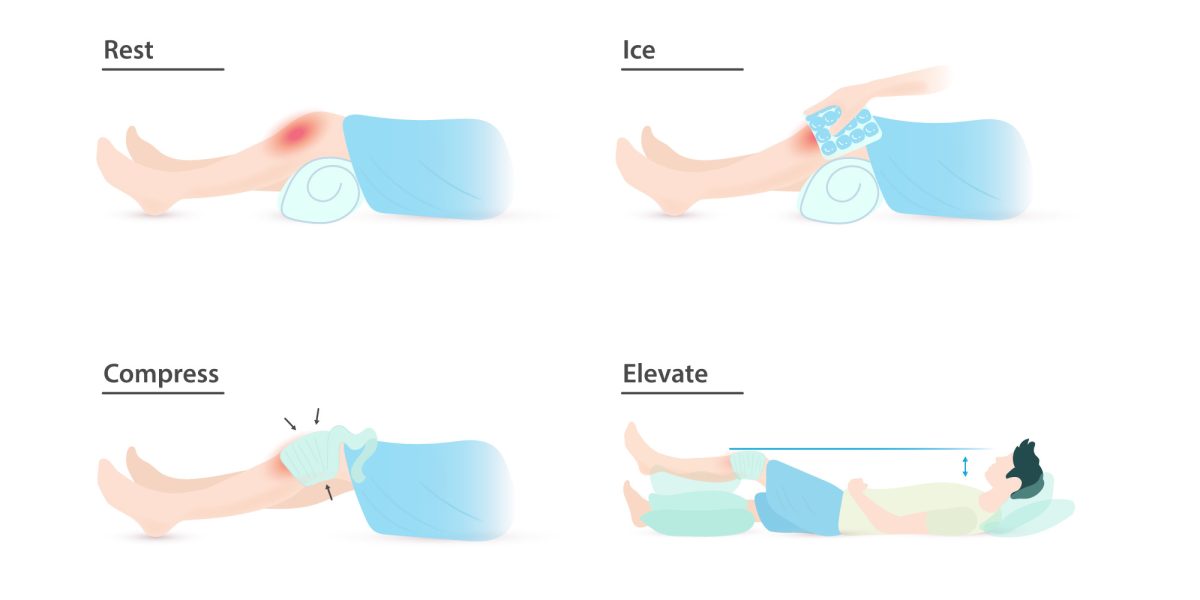

Have you ever been instructed to use the RICE protocol? Maybe you twisted your ankle on a root, slipped and fell hard on a patch of ice, or pulled your hamstring in an intramural soccer match. Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation is the common advice for immediate management of a soft tissue injury. But when you wrap a swollen calf, cover it with ice, and prop it on a pillow, what is actually going on beneath the skin? You may be able to feel the numbing cold of the ice and the compressive pressure of the wrap, but what about the healing processes that are harder to distinguish?

Skeletal Muscle Damage

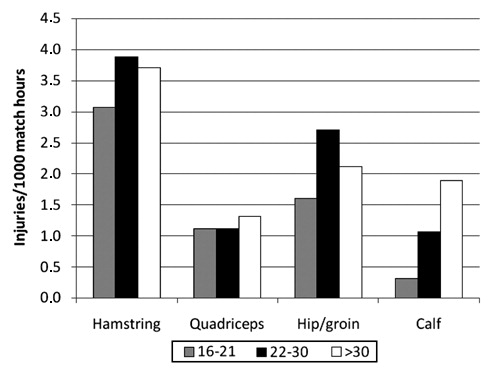

Skeletal muscle is the tissue responsible for voluntary movement, used in everyday life for basic functions such as walking, running, or jumping. The tissue is composed of muscle fibers and connective tissue that contracts to generate motion. In competitive sports, injuries commonly involve damage to this muscle, with one study reporting over 30% of professional soccer injuries being muscle-related. Most commonly, muscle “strains” occurred in four main regions, shown below.

Match Incidence of 4 Most Common Muscle Strain Injuries in Age Groups 16-24 Years, 22-30 Years, and >30 Years (Modified from Ekstrand, et al., The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2011)

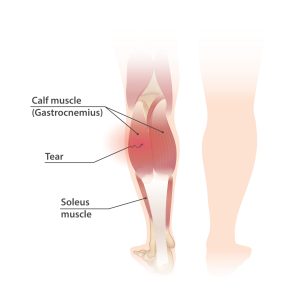

Muscle strain injuries involve the stretching of muscle fibers to the point of failure, potentially even causing the fibers to tear apart.

Calf Muscle Strain and Tear (injurymap.com)

When a tear occurs, the body’s immune system works to repair the fibers in the region. A tissue scar forms in the gap left by the tear while an extra store of cells (satellite cells) mature and eventually fuse into the damaged fibers. Applying the RICE method during this time of healing impacts this immune response.

R: Rest

In 2012, Jarvinen and Lehto demonstrated in rat muscle that a period of immobilization following injury limits the size of the tissue scar that forms. Excessive scarring makes it difficult for the muscle fibers to reconnect. However, the study also showed that a quicker return to movement resulted in these fibers better growing to match uninjured fibers in the tissue. Additionally, waiting too long to return to activity can result in muscle atrophy. Thus, depending on the specific injury, the precise timing of a “rest” period should balance pain management and injury prevention with promoting the best possible healing results. Importantly, the return to movement is not an immediate return to competitive athletics, but it is a step up from the time on a couch one might imagine during a time of “rest.”

I: Ice

While the numbing cold of an ice pack may bring instant relief after injury, perhaps surprisingly the use of ice to treat damaged tissues also has complicated effects on the healing process. Hurme et. al. in 1993 found that in addition to reducing pain, the application of cold therapy resulted in a reduced inflammatory response. This response is necessary in the healing process for ultimately promoting the regeneration of muscle fibers. However, even if the application of cold slows the healing process, reduced pain may allow for a quicker return to movement and thus better quality fiber formation, thus presenting another tradeoff.

C: Compression

Applying compressive pressure to an injured site provides support, reduces swelling from the accumulation of fluid, and promotes circulation. Thus, compressive treatment is able to support the healing process and proper formation of new muscle fibers. Through clinical studies, compression sleeves have been shown to promote quicker restoration of function and reduce swelling, soreness, and levels of a protein marker of muscle damage (creatine kinase).

E: Elevation

The elevation of an injured tissue uses the force of gravity to reduce swelling. Similar to the force of compressive pressure, this may help promote the healing process, though specific experimental evidence in support of such a mechanism is currently lacking.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the exact mechanisms and trade-offs associated with using the RICE method to treat muscle injuries are still not fully understood. Levels of activity, temperature, and the physical forces of compression and elevation all influence the body’s healing response in some way. Increasing our understanding of the exact mechanisms by which the RICE treatment interacts with the immune response may help us to better work with the body’s immune processes to restore muscle function post-injury.