Featured image courtesy of InjuryMap.

Joint degenerative diseases, such as Osteoarthritis, are an increasing cause of pain and disability in millions of people worldwide, per Sanchez-Adams et. al. As a culture of intense, nonstop work is promoted, people incline to not give their bodies enough time to rest, which has increased the cases of joint injuries, especially those to the lower body; specifically in those populations that are exposed to high intensity physical activity. This is concerning, since it has been discovered that joint injuries provoke an alteration in how these joints distribute loads, drifting from their physiological, or typical/natural, behavior, as demonstrated by Ko et. al. Consequently, this affects the biological response of the bone and cartilage that compose that affected joint, leading to potential degeneration due to the altered mechanotransduction (interpretation of mechanical signals to biochemical ones) interactions of the cell and cartilage forming cells, osteocytes and chondrocytes. This degeneration is what characterizes the concerning and debilitating Osteoarthritis (OA). This leads us to our questions: Why does the altered loading affect my joints? If I suffer an injury, can I prevent the degeneration of my joints and live a long, healthy life?

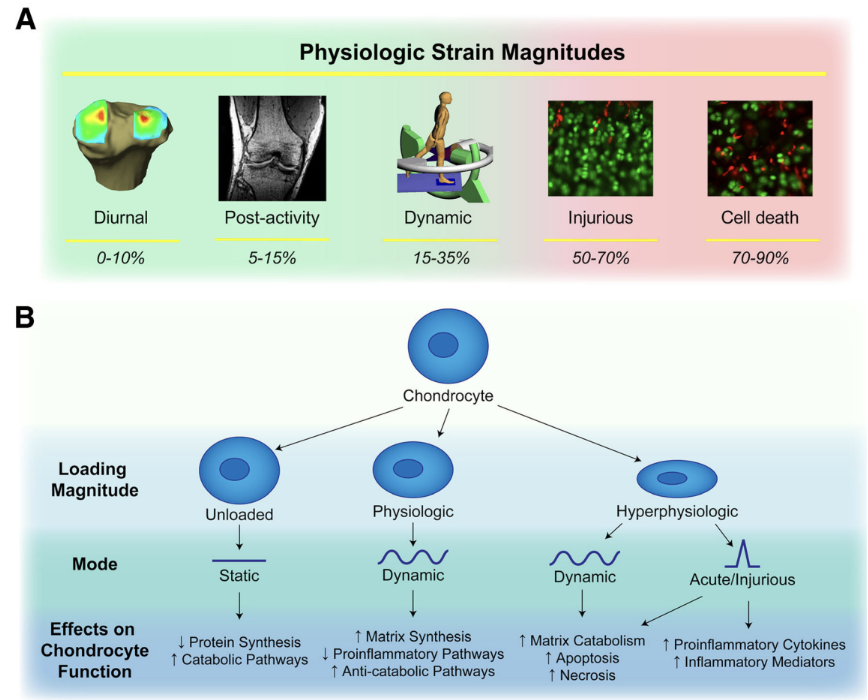

In the biological realm, forces are always influencing processes, affecting the activities that cells choose to perform. In the case of chondrocytes, a physiological (or normal) loading promotes processes necessary for the optimal performance of cartilage in joints. On the other hand, excessive straining of the cartilage provokes these cells to undergo apoptosis, or programmed death, especially on patients that suffered joint injuries that concluded in the partial or complete loss of cartilage, as illustrated in figure 1.

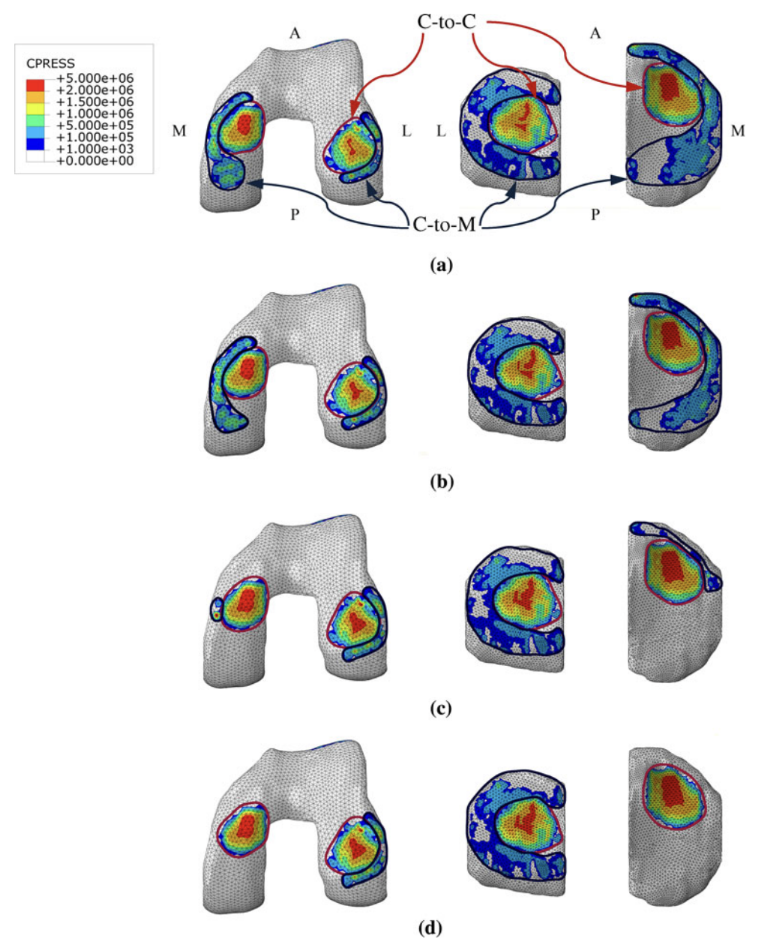

As mechanically defined, stress is force exerted over an area, meaning that if the force is constant, a smaller area will feel a higher stress than a bigger one. Joint injuries typically translate to loss of cartilage or ligament, which reduces the area of contact for the forces, increasing the stress that the cartilage receives, reaching non – physiological levels by creating stress concentration points, or areas of higher stress, promoting uncontrolled cartilage degeneration. This also affects the local bone structure, since excessive loadings provoke the bone to adapt and generate bone spurs, which exert even higher stress on the cartilage in the body’s attempt to reach force equilibrium. Looking to characterize this behavior, studies on the effect of different levels of meniscectomy, or removal of the meniscus, in the concentration of loads in knee cartilages were done by Yong Bae et. al. It was determined that when more meniscus tissue was removed due to injury, an alteration in load distribution that is characteristic of osteoarthritis was exhibited.

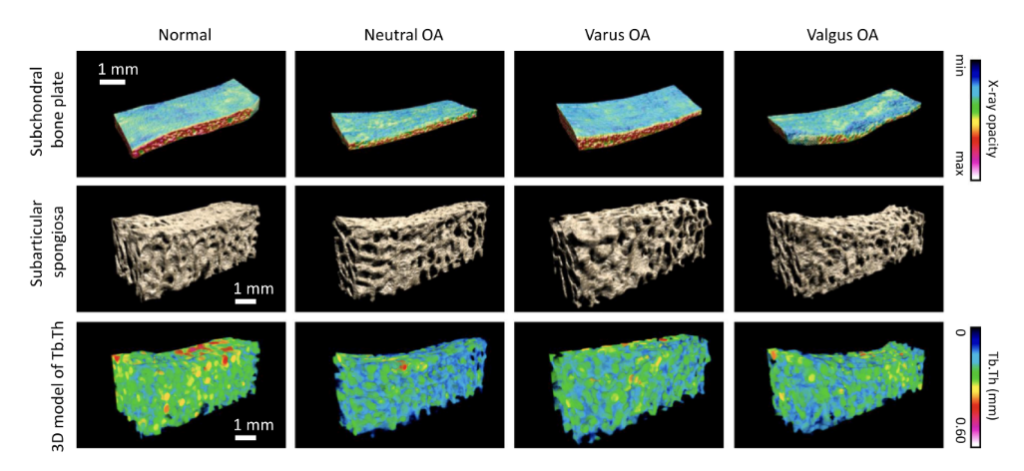

Figure 3. Bone and cartilage turnout in neutral, underloading and overloading of cartilage of sheep with OA (Reinhard et. al, 2024).

Osteoarthritis caused by injuries has been a cause of concern for a long time, especially in recent history, and it is important to apply practices for the promotion of healthy and functional joints. First comes prevention: by living a balanced and active life, not overloading or overworking your body, and by supplying it with the necessary nutrients and rest for optimal recovery. There is also a great effort being made to look for alternatives that reduce the loading on cartilage, returning to physiological conditions, fighting the progression of osteoarthritis. As seen in figure 3, by studying sheep with induced OA, Reinhard et. al determined that by creating an underload (varus), orienting the bone in a ways that loads are better distributed, the alteration of the subchondral (under the cartilage) bone was prevented, subsequently maintaining a healthy cartilage due to the reduction of loading concentrations. These are compelling results, which lead us to a potential future of full-joint injury recovery therapies with no repercussions in the long term for our musculoskeletal system health, a crucial step for a productive and healthy population.