by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

The story behind the statues is well known: a young CSC priest, William Corby, offered a general absolution to members of the Irish Brigade, part of the Second Corps of the Union’s Army of the Potomac, minutes before the soldiers engaged in fierce fighting late on the second day of the battle at Gettysburg (July 2, 1863).

Corby served as chaplain to the 88th New York Infantry, which was part of the famous Irish Brigade. This group of soldiers were mostly Irish and Irish-American Catholics from New York and Philadelphia who were formed from five regiments: three from New York (the 69th Infantry, 63rd Infantry, and 88th Infantry), the 28th Massachusetts Infantry, and the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry. After the war Corby returned to the University of Notre Dame where resumed his teaching position; he later became the school’s president.

The priest had given general absolution to his flock of mostly Irish Catholic soldiers before, most notably at Antietam in September 1862, just before the brigade suffered heavy casualties. But this time, as fighting raged around the soldiers at Gettysburg, when Corby climbed up on a boulder and spoke, not just the Irish Brigade but the whole Second Corps fell silent. It was a moment that many officers and soldiers remembered later. For many Catholics it came to mean recognition, if not full acceptance, by their non-Catholic fellow Americans.

Less well known is how the statues materialized. The Catholic Alumni Sodality of Philadelphia spearheaded the project and reported it in this pamphlet. The sodality had been formed in 1902 to promote faith and collegiality among Catholic men who were college graduates. The sodality implemented the statues’ financing and creation, but it acted on an idea of St. Clair Mulholland, commander of the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and witness to Corby’s actions at Gettysburg.

Less well known is how the statues materialized. The Catholic Alumni Sodality of Philadelphia spearheaded the project and reported it in this pamphlet. The sodality had been formed in 1902 to promote faith and collegiality among Catholic men who were college graduates. The sodality implemented the statues’ financing and creation, but it acted on an idea of St. Clair Mulholland, commander of the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and witness to Corby’s actions at Gettysburg.

The Irish-born Mulholland was just 23 years old when he began serving as a Lieutenant Colonel of the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry in 1862. He fought in some of the war’s major battles, including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and of course, Gettysburg.

After the war Mulholland dedicated himself to commemorating Civil War soldiers, particularly the Irish Brigade. In 1888 he led the initiative to raise a monument to the brigade at Gettysburg. The Alumni Sodality of Philadelphia embraced the idea of creating a memorial to Corby only after a member heard Mulholland speak movingly about the incident. It was a speech the old soldier had given countless times over the years.

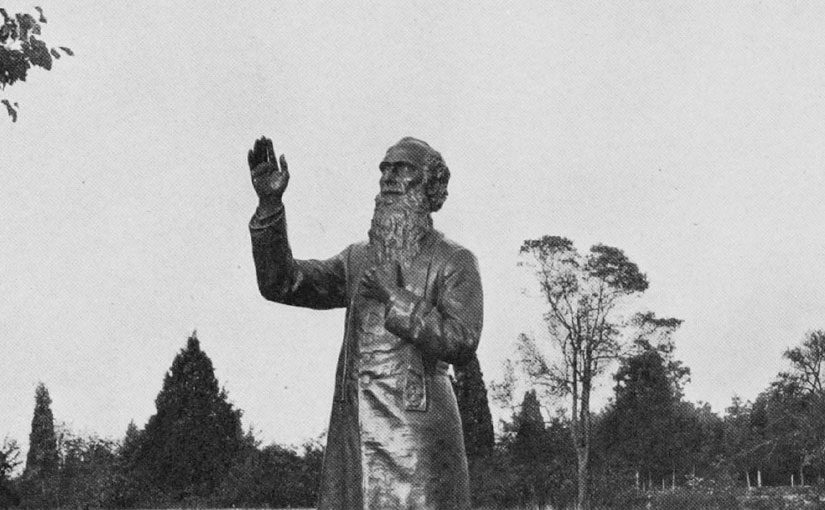

The sodality hired sculptor Samuel Murray to create the monument. It was placed at Gettysburg, amid an extensive program of speeches and dignitaries, on October 29, 1910. A replica, created by the artist, was mounted on Notre Dame’s campus on Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day), 1911.

Mulholland and the sodality were not unique in remembering those who served. Between the end of the war and the 1930s thousands of Civil War monuments rose around the nation. As we have seen in recent disputes over monuments in the United States, public statues have multiple uses and their meanings change over time. Monuments evoke the past even as they convey contemporary expectations about class, race, gender, and religion.

As this pamphlet reminds us, Corby’s memorialization was about more than the priest’s service. It created a narrative of Catholic loyalty and patriotism at a time when American nativism was again on the rise, sparked by large immigration from southern and eastern Europe. By focusing on a priest rather than on Catholic soldiers, the statue’s creators deemphasized the larger Irish Catholic experience of the war, fueled as it was by a mix of American patriotism, Irish Republicanism, and economic need. The image reinforced instead a message of cleric-led, middle-class Irish American respectability. [1]

[1] Randall M. Miller, “Catholic Religion, Irish Ethnicity, and the Civil War,” in Religion and the American Civil War, Randall M. Miller, Harry S. Stout, and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds., (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 285-86.

A happy Memorial Day to you and yours

from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

2016 post: Memorial Day: Stories of War by a Civil War Veteran

2017 post: “Memorial Day” poem by Joyce Kilmer

2018 post: “Decoration Day” poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

2019 post: Myths and Memorials

During June and July the blog will shift to a summer posting schedule, with posts every other Monday rather than every week. We will resume weekly publication August 10th.

The anthology

The anthology