We join the Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month.

From our Latin American and Latino Studies Archives: Celebration and Resistance

by Payton Phillips Quintanilla, Latin American & Iberian Studies Librarian and Curator

2025 has seen various local and community-based annual public celebrations of Latino heritage scaled-down, postponed, or cancelled altogether out of fears for the safety of participants and community members. Other public celebrations have gone on as planned, with some organizers even rearticulating their yearly “Grito de Independencia” (the September 15th commemoration of the “Cry of Independence” from Spanish colonial rule, specific to the Mexican context) as “Grito de Resistencia” (“Cry of Resistance”). Both paths, however, are guided by a spirit of solidarity, and informed by a history of perseverance, that predate—and are poised to persist beyond—any formal federal recognition of the diverse cultures, accomplishments, and contributions of Latinos in the United States.

Inspired by that same spirit and history, we present three examples, preserved in Notre Dame’s Rare Books and Special Collections, of historical moments when Latino communities organized celebrations of resistance—both public and private, and throughout the calendar year—in direct response to histories and realities of persecution, oppression, exclusion, and erasure.

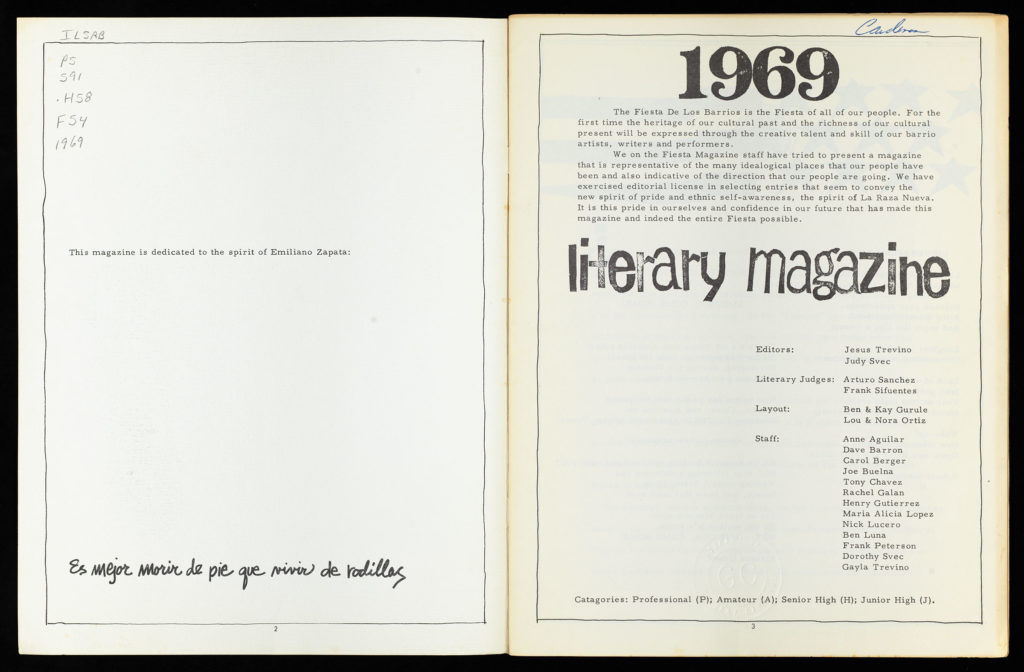

1969: “La Fiesta de los Barrios”

“The Fiesta De Los Barrios is the Fiesta of all of our people. For the first time the heritage of our cultural past and the richness of our cultural present will be expressed through the creative talent and skill of our barrio artists, writers and performers. […] It is this pride in ourselves and confidence in our future that has made this magazine and indeed the entire Fiesta possible.”

The name “La Fiesta de los Barrios” carries multiple references: it was a community celebration, a literary journal, and an aspiration for the future. The actual “fiesta” took place in early May, 1969, at Lincoln High School in Los Angeles to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the LA Walkouts: a watershed movement through which Mexican American students protested systemic racism, abuses, and neglect on their campuses, and demanded inclusive and unbiased curricula. (For an introduction to the Walkouts, we suggest you watch this Retro Report hosted by PBS, or this excerpt from PBS’s Latino Americans.)

The journal by the same name, or Fiesta Magazine (MSH/LAT 0099-61), memorialized select verse, prose, and drawings created by community members and event participants, representing a diversity of voices and experiences. And finally, it was the hope, as articulated by photographer Pedro Arias in one of the journal’s opening essays, that all peoples of Mexican descent living in the United States could overcome generational and cultural divides to work together toward common goals: “Y entonces será un día de fiesta, será una FIESTA DE LOS BARRIOS, pero una Fiesta de Los Barrios permanente […]” (And then it will be a day of celebration, it will be a FIESTA DE LOS BARRIOS, but a permanent Fiesta de Los Barrios […]) (7).

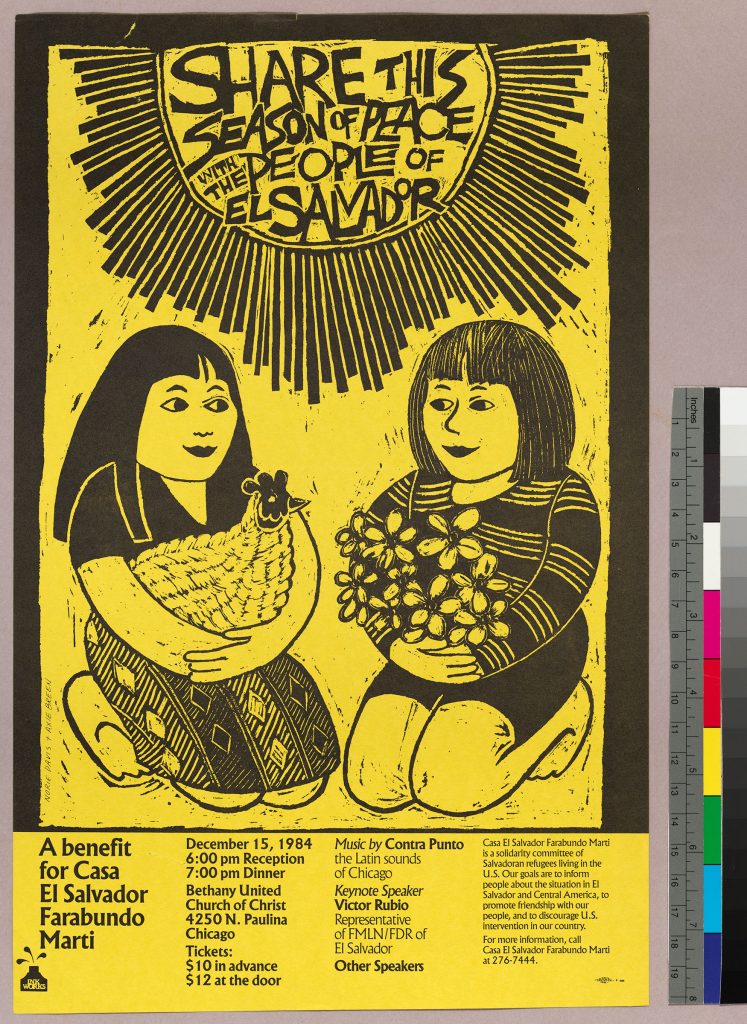

1984: “A benefit for Casa El Salvador Farabundo Martí”

“Casa El Salvador Farabundo Martí is a solidarity committee of Salvadoran refugees living in the U.S. Our goals are to inform people about the situation in El Salvador and Central America, to promote friendship with our people, and to discourage U.S. intervention in our country.”

In December 1984, the Chicago-based, refugee-led organization called Casa El Salvador Farabundo Martí hosted a benefit dinner and invited allies and supporters to “share this season of peace with the people of El Salvador.” El Salvador itself, rather than celebrating a season of peace, was deep in a brutal civil war marked by widespread human rights abuses: far from a conflict confined to fighting between armed factions, the government’s military and paramilitary death squads—trained and funded by the United States government—broadly targeted civilian non-combatants. Meanwhile, only a minuscule portion of refugees fleeing El Salvador were granted asylum in the United States. This combination of domestic U.S. policies, enabled by controversial Cold War rhetoric, sparked passionate peace, solidarity, and anti-intervention movements across the country. A snapshot of those efforts, and the array of allies that were involved in them, are captured in this small poster (MSH/LAT 0120 U.S./Central America Cold War Ephemera Collection).

(If this historical moment and its relationship to “sanctuary” activism is unfamiliar to you, an article published earlier this year in The Conversation is a good place to start reading.)

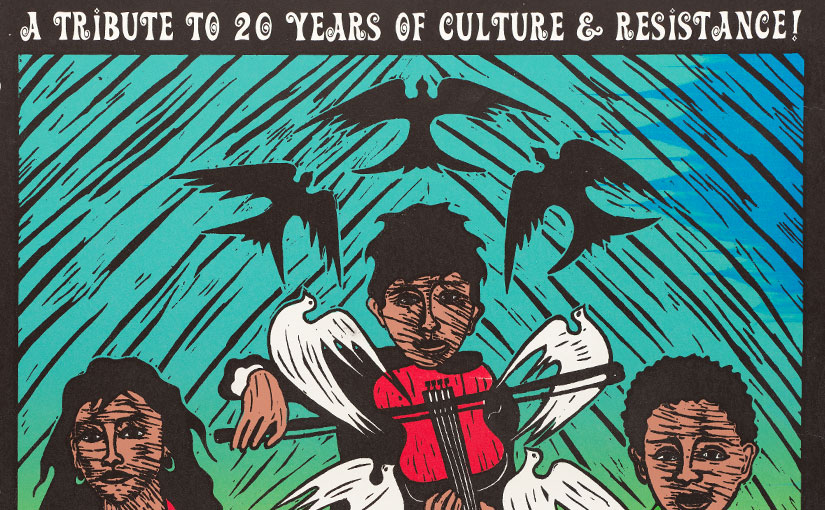

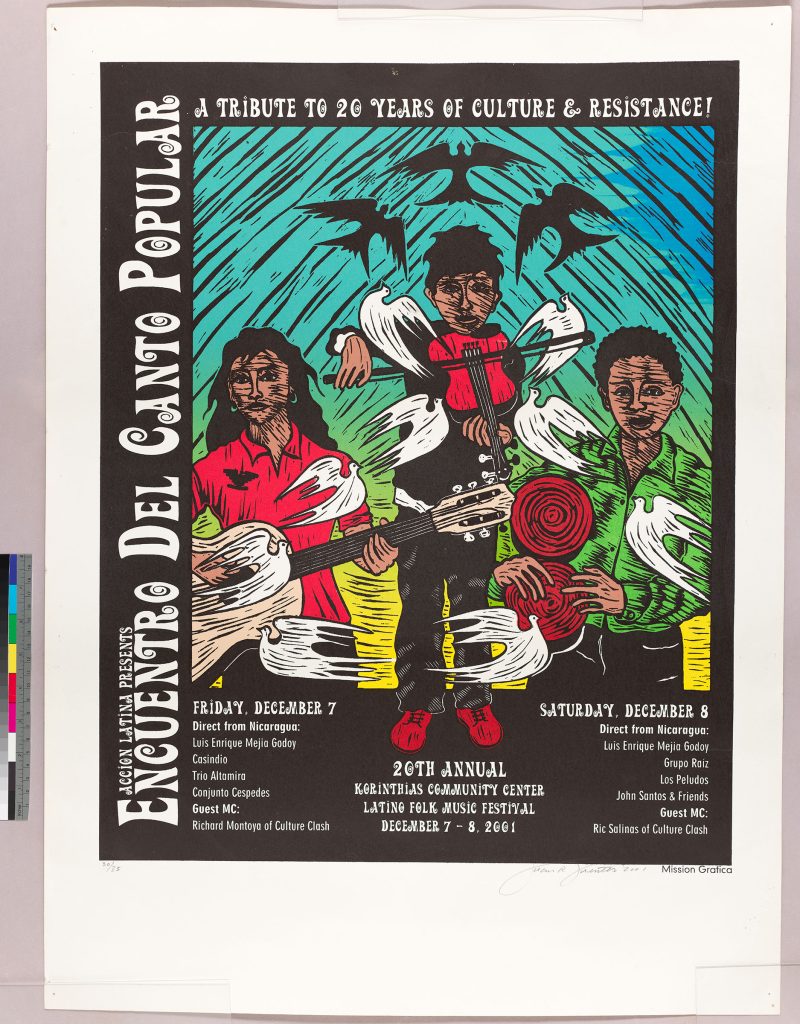

2001: “Encuentro del Canto Popular”

“A Tribute to 20 Years of Culture and Resistance”

San Francisco’s first annual “Encuentro del Canto Popular” (“Gathering of Popular Song”) was organized by volunteers from the community newspaper El Tecolote in 1982. The event was inspired by the life and legacy of Víctor Jara, a Chilean educator, activist, and singer-songwriter who was one of the founding figures of Chile’s—and, ultimately, Latin America’s—nueva canción (new song). This folkloric genre was imbued with such deep social commitment that it became an international movement (the Smithsonian offers an introduction to la nueva canción in their Folkways series). Jara was kidnapped, imprisoned, tortured, and executed by Chile’s military just after the U.S.-backed coup that ousted the democratically-elected president, Salvador Allende, and which began the 17-year military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

Acción Latina, a community organization based in San Francisco’s Mission District that grew out of El Tecolote, took part in U.S.-based protests against Pinochet’s regime (as can be seen in this post from the Bancroft Library, which now preserves a substantial Acción Latina archive), as well as later solidarity movements. The poster featured here was created for the Encuentro’s 20th year, celebrated in 2001 under the stewardship of Acción Latina. Its lineup of musicians from Nicaragua for this “tribute to 20 years of culture and resistance” was a nod to the protest and dissent expressed in both Nicaragua and the United States following the CIA-led formation in 1981 of the Contras (an umbrella organization of anti-Sandinista combatants), a covert project that ultimately culminated in the Iran-Contra Scandal. The musician wearing the symbol of the United Farm Workers on her shirt speaks to solidarity within and between Latino communities.

Previous Hispanic Heritage Month Blog Posts:

- 2024: Reading Beisbol: Semanario Especializado

- 2023: An Hispanic Superhero in Southwest Texas

- 2022: United Farm Workers

- 2021: Migratory History from a Child’s Point of View

- 2020: The Woodcuts of Consuelo Gotay

- 2019: Latinx Ephemera Collection

- 2018: Puerto Rican Artists

- 2017: Sergio Sánchez Santamaría