Katmai National Park in Alaska holds an annual “Fat Bear Week”, in which Twitter followers are asked to vote for the fattest bear in the park. This year’s winner was Holly, somewhere in the range of 500 to 700 lbs. That’s a big bear. However, in 1960, a male polar bear in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska, weighed in at 2,209 lbs. In fact, on average, polar bears weight up to 60% more than Grizzly bears, their closest animal relative.

So just how did Polar Bears get so big? Well, as anyone in the Midwest knows, a harsh winter requires a good winter coat. The advantage of thick skin and fur, as well as a higher capacity to put on weight made heavier polar bears more adept to survive. However, bigger bears that could survive the cold were more likely to fall through the ice, so these adaptations required better foot mechanics.

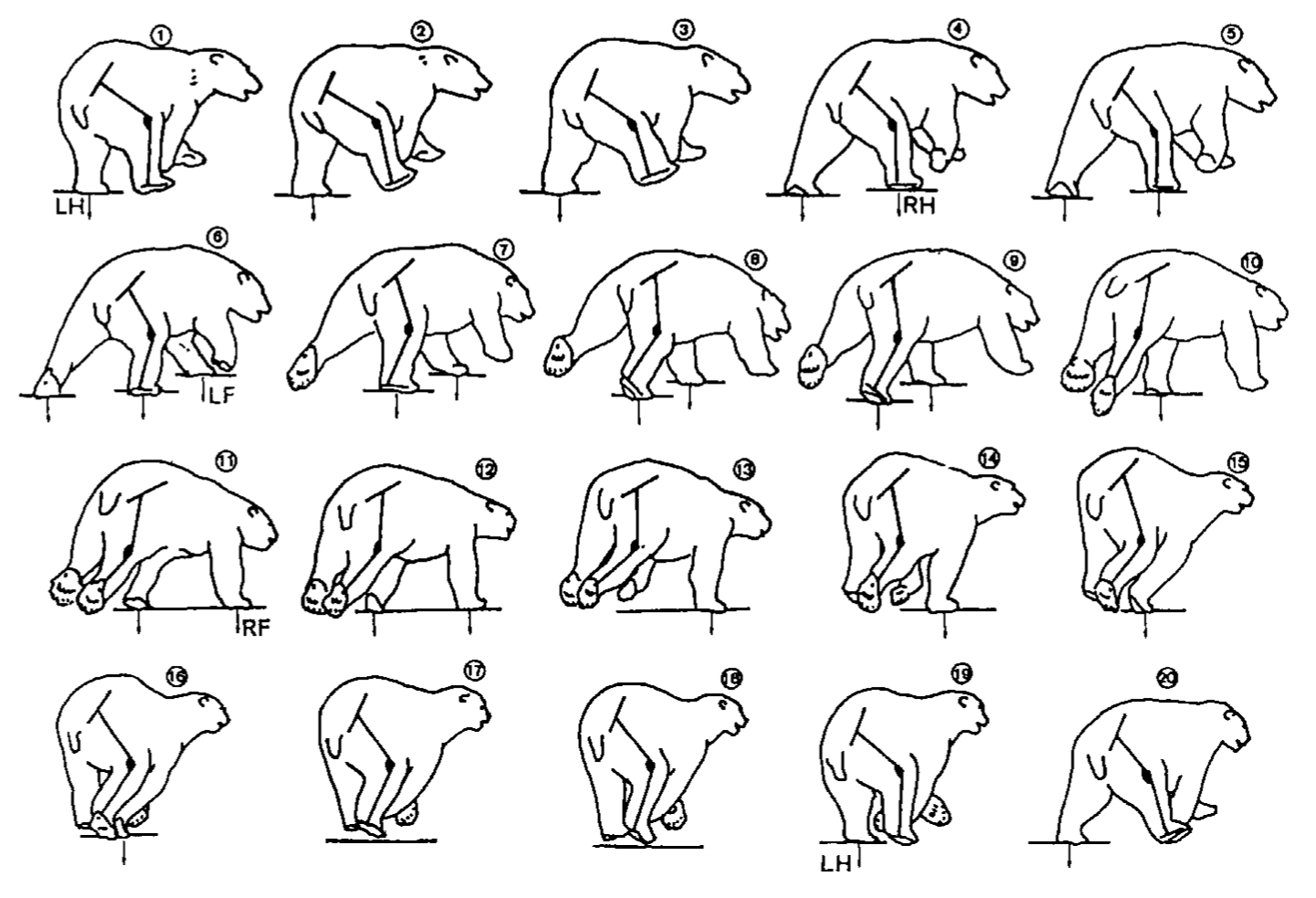

Consequently, polar bears developed a distinctive gait. A rotary gait is a “double suspension” gait, meaning the animal bounces both off the hind limbs and then the fore limbs . This is contrasted from the grizzly bear’s transverse gallop, which involves only one “bounce,” — this loads each limb for a longer time and more vertically. The rotary gait improves stability, giving the polar bear the ability to travel quickly and smoothly on icy surfaces.

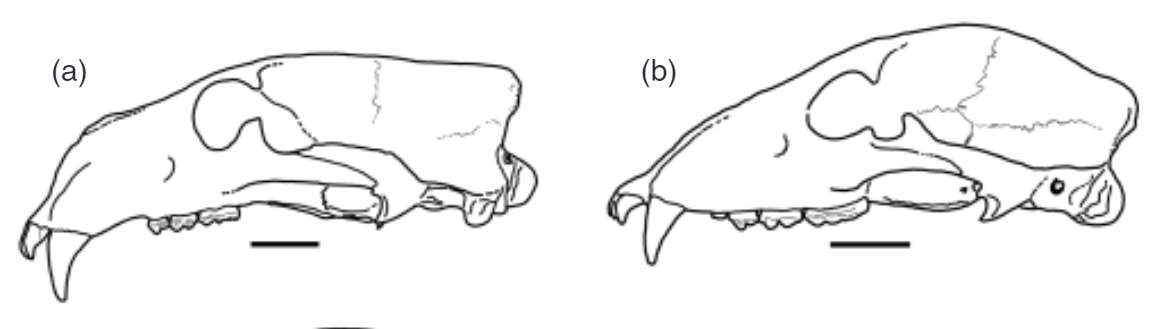

Another significant difference between the species are their skulls, which, while similar in size, vary greatly in bite force and bone strength. The polar bear has a stronger bite, but a weaker skull. Polar bears are one of the most rapid instances of evolution in surviving species of animals, having evolved from the grizzly bear within the last five hundred thousand years. So why are their skulls weaker if their bite is stronger?

Simply put: seals are easy to chew. Grizzlies are omnivores, as most bear species. Their diet subsists of salmon, elk, and small game, but includes a hefty amount of vegetation. Polar Bears, in the ice and cold, were forced to eat seals (as well as penguins, fish, even belugas). Seals are largely blubber, providing the caloric intake necessary to sustain these large beasts, but offering little resistance in the chewing process.

The polar bear’s skull morphed quickly, elongating to allow it to hunt for seals and fish through small holes in the ice. This weakened and lowered the density of the skull; however, because the seal-heavy diet required less effort to chew than vegetation, there was no selective advantage to a skull reinforcing. So, with a more efficient gait and a stronger bite, the polar bear developed into a killing machine in the icy north.

Interested in more of the polar bear’s hunt? Learn about how they can swim for hundreds of miles, or to see these arctic advantages in action, check out this video of a polar bear hunting a seal.

Featured image cropped from “polar bear pair” by USFWS Headquarters which is licensed under CC BY 2.0.