Ancient records and relics suggest that upright birthing positions, such as kneeling, squatting, sitting, and standing, were the predominant method of childbirth throughout human history. Moreover, a 1961 study found that only 14 of 76 existing traditional cultures assumed dorsal positions during childbirth. However, upright childbirth was largely abandoned in the West during the medicalization of labor and delivery between the 14th and 16th centuries. The shift from upright to horizontal birthing norms is largely attributed to the French physician François Mauriceau. In his book, The Diseases of Women with Child and in Child-Bed, he advocated for the semi-recumbent birthing position, whereby the laboring mother lays on her back with her head and shoulders slightly raised (Dundes, 1987). Today, this standard is generally undisputed among physicians and expectant mothers in Western nations. However, experts argue that this norm is largely rooted in interventional convenience and is perpetuated by modern technologies such as continuous monitors and anesthetics, which constrain movement. Here, an examination of clinical and biomechanical data sheds light on the complexities surrounding this topic.

Clinical data are essential for understanding the relationship between birthing postures and health outcomes. For instance, clinical analysis demonstrates a link between upright birthing positions and reduced occurrences of fetal heart rate abnormalities. On the other hand, upright births are linked to an increased risk of perineal tearing, postpartum hemorrhage, and sphincter ruptures. This is attributed to the fact that visualization of the perineum, the region between the anus and vagina, allows physicians to provide support, which reduces lacerations. Even so, mothers who give birth in an upright position report reduced labor pains. Upright birthing is also associated with shorter delivery times, reducing the duration of labor by an average of one hour compared to mothers who deliver in a horizontal position (Desseauve et al., 2016). Given these complex considerations, a biomechanical perspective is currently lacking in clinical practice and is necessary to understand the effects of various birthing postures on both mother and child.

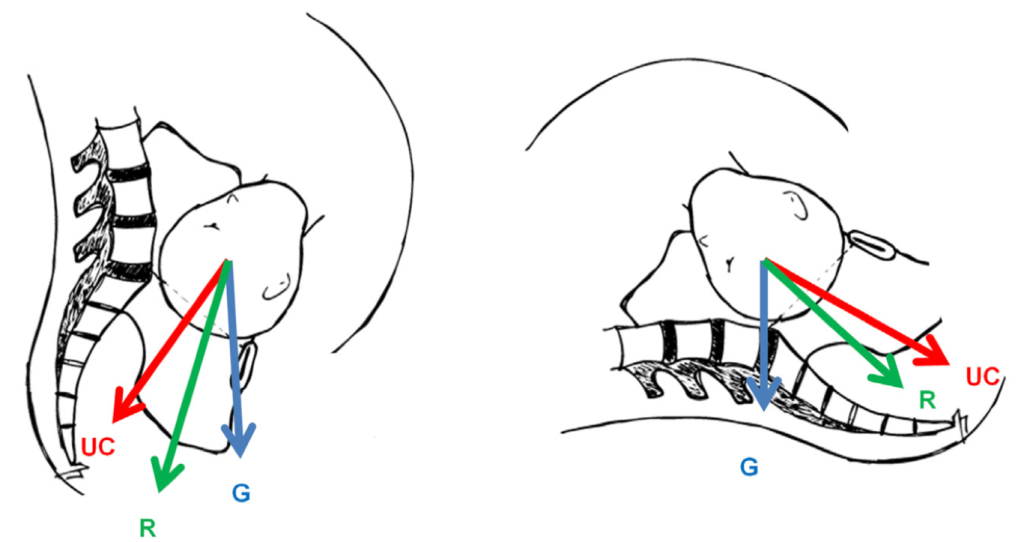

Several biomechanical studies assess the effects of spinal flexion, pelvic orientation, and thigh extension on pelvic dimensions. Biomechanical analysis suggests that tilting the sacrum, or the base of the spine, about the pelvis can increase the diameter of the pelvic inlet, reducing the risk of pelvic dystocia, whereby the pelvic bones obstruct the pathway of delivery (Desseauve et al., 2016). Borges et al. provide a complex computer simulation that models the effects of tailbone flexion during labor on pelvic dimensions and widening of the pubic symphysis, the joint linking the left and right pubic bones. The model demonstrates that birthing positions that allow for sacrum tilting, such as kneeling, standing, squatting, and sitting, increase pelvic space and decrease stresses on the pubic symphysis. Meanwhile, horizontal birthing practices place weight on the sacrum and restrict movement, leading to reduced pelvic space and increased joint displacement. This suggests that upright positions, which allow for greater spinal mobility, may reduce the risk of fetal obstruction or pelvic separation during childbirth.

There is a case for both upright birthing postures and current horizontal standards. The current birthing norms aid in physiological monitoring and facilitate immediate interventions in an emergency. On the other hand, traditional upright birthing practices may improve maternal comfort, reduce laboring time, and decrease the chances of dystocia. From a purely biomechanical perspective, some evidence suggests that upright postures are better suited to the mechanical processes of the body during childbirth. However, optimization likely depends on the individual circumstances of each delivery.