Notre Dame Special Collections holds approximately 132,000 volumes of rare books and periodicals. In the collection, there are really old books and really new books; books that have high monetary value and books that don’t; books with paper covers and books with hard covers; books that look like books and books that look like art. What is a rare book then? Why is one book in the rare book collection and not another? And exactly what kinds of rare books does ND Special Collections have?

The mixture of old and new and varying monetary values and formats points to the fact that it’s hard to define precisely what a rare book is. Perhaps the question isn’t so much, “What is a rare book?” but rather, “What makes a book rare?” Supply and demand play a large role. If there are only a couple of copies of a particular book, it seems logical to believe that that book is rare; however, if no one is interested in acquiring that book, then the book isn’t necessarily rare. If there is greater demand than the number of books available to meet demand, then a book may be said to be rare. High demand, though, is only one part of the equation in determining whether a book is rare.

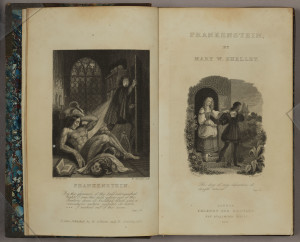

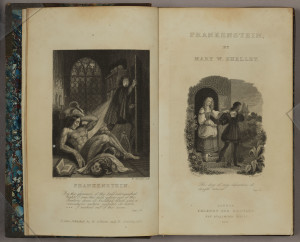

Above and beyond supply and demand, a book must have some sort of intrinsic value or importance. That is, what importance does a book have in the field of study to which it belongs? More simply put, does the book have research value? For example, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus, first published in 1818, is quite popular and readily available whether in your local library or through any of a number of bookstores and online booksellers. But editions of this book are found in special collections. Both the original 1818 edition and the 1831 revised edition published in a single volume by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley have intrinsic value for literary studies. The first presents Shelley’s ideas in 1818 before she suffered from multiple personal tragedies—the deaths of her son, daughter, and husband, of her friend, George Gordon (Lord Byron), and being betrayed by her friend, Jane Williams. The third edition, considerably revised by the author, reflects the change in her philosophical ideas. After suffering these tragedies Shelley revised the text to exemplify her belief that human events are not decided by free will but by material forces beyond human control.

Above and beyond supply and demand, a book must have some sort of intrinsic value or importance. That is, what importance does a book have in the field of study to which it belongs? More simply put, does the book have research value? For example, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus, first published in 1818, is quite popular and readily available whether in your local library or through any of a number of bookstores and online booksellers. But editions of this book are found in special collections. Both the original 1818 edition and the 1831 revised edition published in a single volume by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley have intrinsic value for literary studies. The first presents Shelley’s ideas in 1818 before she suffered from multiple personal tragedies—the deaths of her son, daughter, and husband, of her friend, George Gordon (Lord Byron), and being betrayed by her friend, Jane Williams. The third edition, considerably revised by the author, reflects the change in her philosophical ideas. After suffering these tragedies Shelley revised the text to exemplify her belief that human events are not decided by free will but by material forces beyond human control.

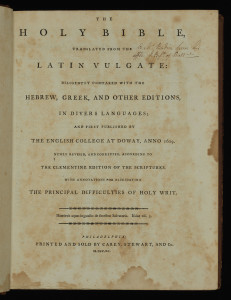

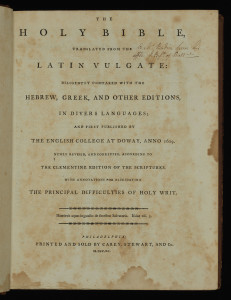

A book might be considered rare if it is the first printing, has particular historical importance, or has specific significance to a particular collection, institution, or other setting. The Holy Bible printed by Matthew Carey in 1790 is one example of all three of these considerations. The Carey Bible represents the printing of the first Catholic Bible in the United States, known also as the Douay-Rheims version. The specific copy of this Bible held in ND Special Collections has further significance to the campus. Locally referred to as “The Badin Bible,” the three volumes comprising this copy were given to Father Stephen Badin (1768-1853) by Bishop John Carroll (1735-1815), the first bishop appointed in the U.S. Father Badin founded a school and church for the Potawatomi Indians, the site of which is now part of Notre Dame’s campus. He also purchased land and gifted it to the Diocese of Vincennes; this land was the parcel upon which the Notre Dame campus was built. ND’s copy of this Bible contains a handwritten dedication to Badin and the ex libris bookplate of Stephen T. Badin.

A book might be considered rare if it is the first printing, has particular historical importance, or has specific significance to a particular collection, institution, or other setting. The Holy Bible printed by Matthew Carey in 1790 is one example of all three of these considerations. The Carey Bible represents the printing of the first Catholic Bible in the United States, known also as the Douay-Rheims version. The specific copy of this Bible held in ND Special Collections has further significance to the campus. Locally referred to as “The Badin Bible,” the three volumes comprising this copy were given to Father Stephen Badin (1768-1853) by Bishop John Carroll (1735-1815), the first bishop appointed in the U.S. Father Badin founded a school and church for the Potawatomi Indians, the site of which is now part of Notre Dame’s campus. He also purchased land and gifted it to the Diocese of Vincennes; this land was the parcel upon which the Notre Dame campus was built. ND’s copy of this Bible contains a handwritten dedication to Badin and the ex libris bookplate of Stephen T. Badin.

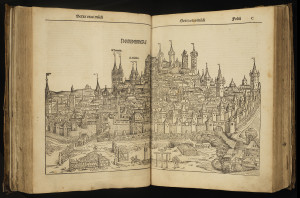

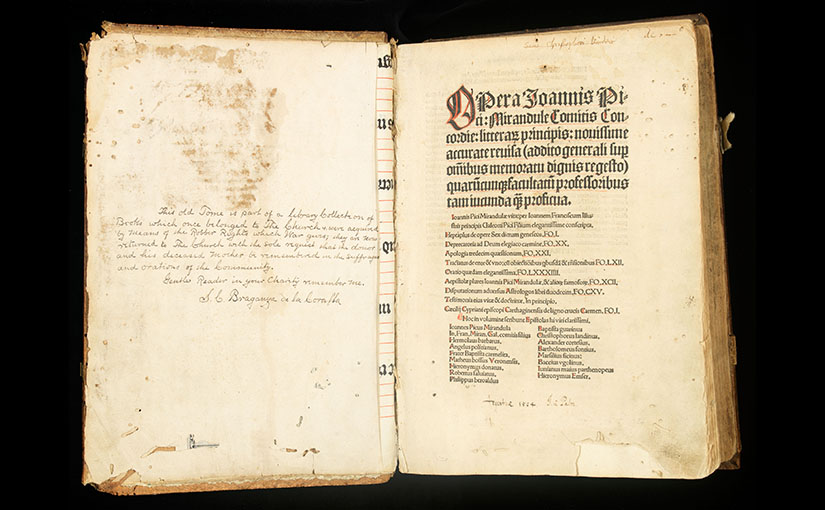

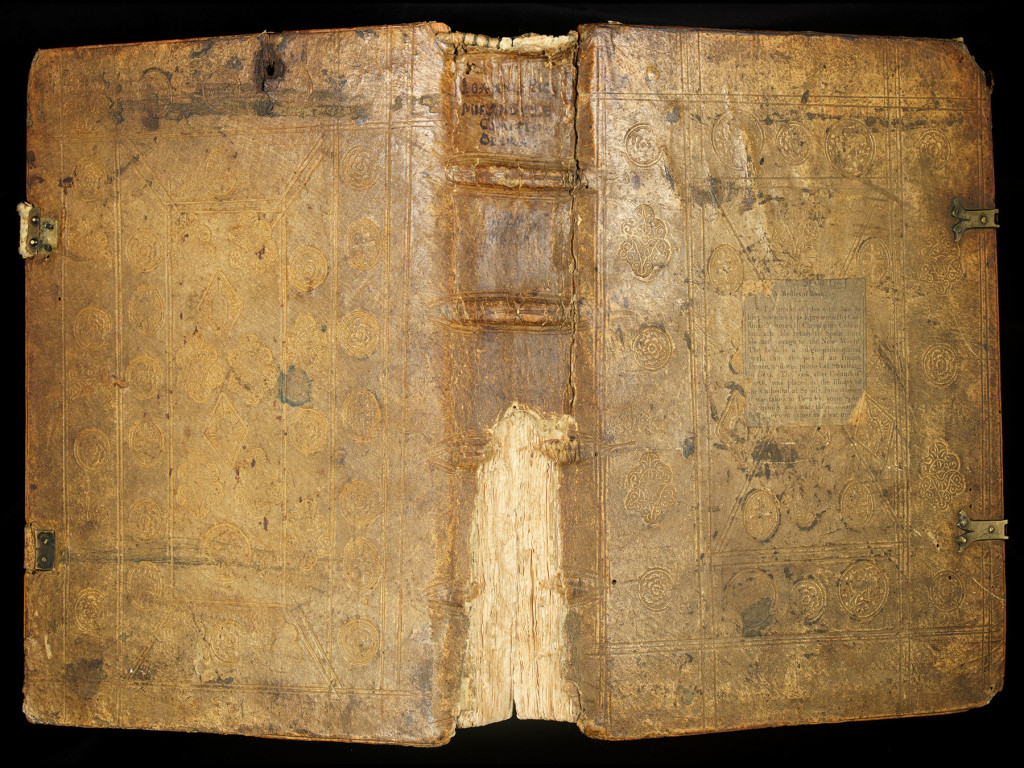

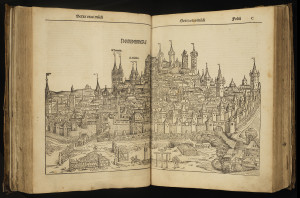

A book that has survived the ravages of time might be a good candidate to be considered rare. For printed books in the western world, a book printed in 1493 and sitting on a shelf today is old—but is it rare? If it has intrinsic importance and if demand outstrips supply, then it most likely is rare. Take RBSC’s copy of the Liber cronicarum by the Nuremberg doctor and scholar, Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514), an incunable—a book printed during the first fifty years of printing in the West (1450-1500)—is a landmark in book design and the history of printing. More commonly known in English as the Nuremberg Chronicle because of its magnificent 2-page woodcut of the city of Nuremberg, this book integrates over 1800 images with the printed text, using the images to explain or clarify the content. The Chronicle also contains woodcuts that provide the first images ever printed of some of Germany’s cities. Though over 1200 copies are known to exist today in libraries throughout the world, the demand for this phenomenal book remains high.

A book that has survived the ravages of time might be a good candidate to be considered rare. For printed books in the western world, a book printed in 1493 and sitting on a shelf today is old—but is it rare? If it has intrinsic importance and if demand outstrips supply, then it most likely is rare. Take RBSC’s copy of the Liber cronicarum by the Nuremberg doctor and scholar, Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514), an incunable—a book printed during the first fifty years of printing in the West (1450-1500)—is a landmark in book design and the history of printing. More commonly known in English as the Nuremberg Chronicle because of its magnificent 2-page woodcut of the city of Nuremberg, this book integrates over 1800 images with the printed text, using the images to explain or clarify the content. The Chronicle also contains woodcuts that provide the first images ever printed of some of Germany’s cities. Though over 1200 copies are known to exist today in libraries throughout the world, the demand for this phenomenal book remains high.

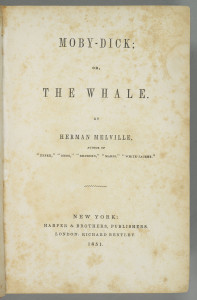

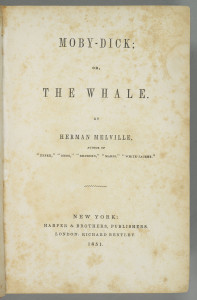

Often, books that are first editions are assumed to be rare books because they are thought to be more valuable. Sometimes that is true, but most books only come out in one edition, making them by default first editions. In the case of books that come out in multiple editions, there are instances when the first edition can add value to the book. For example, Moby Dick by the American author Herman Melville (1819-1891) was published first in October 1851 in London by Richard Bentley as a three-volume set in an edition of 500 copies. 200 copies were bound in spectacular fashion, with seafoam green cloth covers and cream cloth spines adorned with a whale in gilt. Today, locating a copy in this original binding is almost impossible; the supply practically does not exist, yet there is demand for this elegant book. The first American edition was printed a month later by Harper and Brothers. This edition corrected the changes in language and spelling and restored passages that had been excised by Bentley in the London edition, making the first American edition of extreme importance for the history of this book.

Often, books that are first editions are assumed to be rare books because they are thought to be more valuable. Sometimes that is true, but most books only come out in one edition, making them by default first editions. In the case of books that come out in multiple editions, there are instances when the first edition can add value to the book. For example, Moby Dick by the American author Herman Melville (1819-1891) was published first in October 1851 in London by Richard Bentley as a three-volume set in an edition of 500 copies. 200 copies were bound in spectacular fashion, with seafoam green cloth covers and cream cloth spines adorned with a whale in gilt. Today, locating a copy in this original binding is almost impossible; the supply practically does not exist, yet there is demand for this elegant book. The first American edition was printed a month later by Harper and Brothers. This edition corrected the changes in language and spelling and restored passages that had been excised by Bentley in the London edition, making the first American edition of extreme importance for the history of this book.

An edition of a book—the set of copies of a book printed from the same setting of type—other than the first edition may have important value for researchers as well. In 1580, Discorso sopra il giuoco del calcio fiorentino by the Florentine Giovanni de Bardi (1534-1612) was first published. The text was edited three times with the new editions printed in 1615, 1673, and 1688; the last printing of the text was in 1766. Discorso was the first book that described calcio, an early form of football that originated in sixteenth-century Italy; it detailed the rules, how the game was played, and what players were expected to wear. The first three editions contained no more than one plate; however, a fourth edition appeared in 1688. Retitled Memorie del calcio Fiorentino Tratte da diverse Scrittute, this edition had been published to coincide with the marriage of Ferdinand de Medici and Violante Beatrice of Bavaria. Memorie contains additional engraved plates, the original Discorso, a lengthy essay on calcio’s antecedants, a poem in Greek on the sport, and notices and records of the games played. The second edition also contains a description of the calcio match played at the wedding. Part of the Joyce Sports Research Collection, both the 1615 printing of Discorso and the 1688 Memorie provide researchers with valuable resources for studying the sport, printing history, and cultural history.

An edition of a book—the set of copies of a book printed from the same setting of type—other than the first edition may have important value for researchers as well. In 1580, Discorso sopra il giuoco del calcio fiorentino by the Florentine Giovanni de Bardi (1534-1612) was first published. The text was edited three times with the new editions printed in 1615, 1673, and 1688; the last printing of the text was in 1766. Discorso was the first book that described calcio, an early form of football that originated in sixteenth-century Italy; it detailed the rules, how the game was played, and what players were expected to wear. The first three editions contained no more than one plate; however, a fourth edition appeared in 1688. Retitled Memorie del calcio Fiorentino Tratte da diverse Scrittute, this edition had been published to coincide with the marriage of Ferdinand de Medici and Violante Beatrice of Bavaria. Memorie contains additional engraved plates, the original Discorso, a lengthy essay on calcio’s antecedants, a poem in Greek on the sport, and notices and records of the games played. The second edition also contains a description of the calcio match played at the wedding. Part of the Joyce Sports Research Collection, both the 1615 printing of Discorso and the 1688 Memorie provide researchers with valuable resources for studying the sport, printing history, and cultural history.

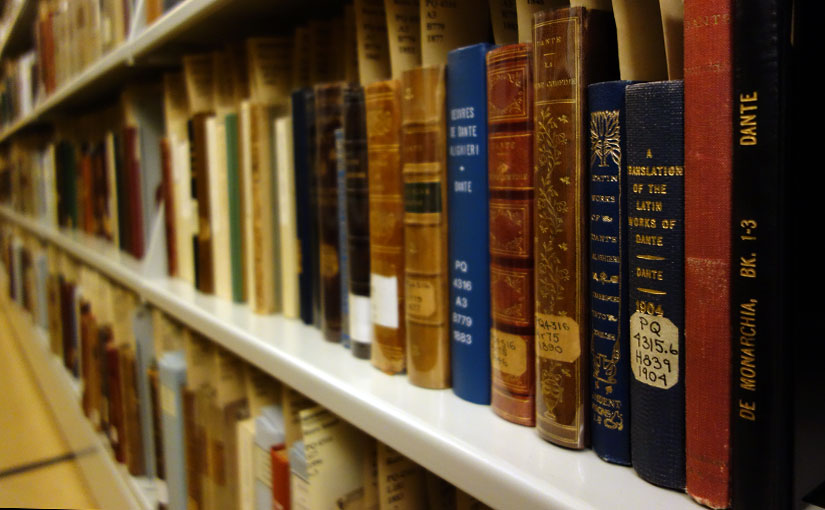

Books that are found in special collections might also be part of a collection that, as a whole, has intrinsic value even if some of the books within that collection are quite common. Many special collections libraries will collect the works of a particular author or field of study. ND Special Collections has a number of these including the Edmund Burke Collection, the Zahm Dante Collection, and the Edward Lee Greene Collection. The core of the Burke Collection is comprised of the personal library of William B. Todd, author of the authoritative descriptive bibliography of Burke’s works. Included are early editions of Burke and his contemporaries including Thomas Paine. Addition volumes have been added to the original collection to comprise a substantial research collection.

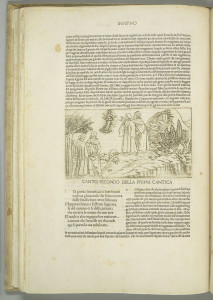

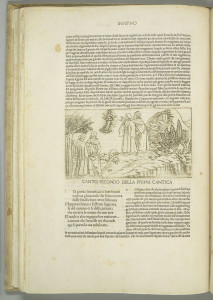

Similar to the Burke Collection is the Zahm Dante Collection of over 3,500 volumes that include incunables, sixteenth-century editions, and important modern works that demonstrate the popularity and impact Dante had on contemporary culture. Represented in this collection are works of fundamental importance in the Dante bibliography, including the 1481 edition of Cristoforo Landino’s commentary and the 1502 Aldine printing of Dante’s Comedia as well as the modern adaptation of Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso by Sandow Birk, which translates the text into contemporary, American English and sets the three works in urban America. The Zahm Dante Collection forms part of the Italian Literature Collection, the most significant Italian literature collection in the United States, containing the works of Petrarch, Boccaccio, Baldassare, Castiglione, Ariosto, Bembo, and Tasso.

Similar to the Burke Collection is the Zahm Dante Collection of over 3,500 volumes that include incunables, sixteenth-century editions, and important modern works that demonstrate the popularity and impact Dante had on contemporary culture. Represented in this collection are works of fundamental importance in the Dante bibliography, including the 1481 edition of Cristoforo Landino’s commentary and the 1502 Aldine printing of Dante’s Comedia as well as the modern adaptation of Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso by Sandow Birk, which translates the text into contemporary, American English and sets the three works in urban America. The Zahm Dante Collection forms part of the Italian Literature Collection, the most significant Italian literature collection in the United States, containing the works of Petrarch, Boccaccio, Baldassare, Castiglione, Ariosto, Bembo, and Tasso.

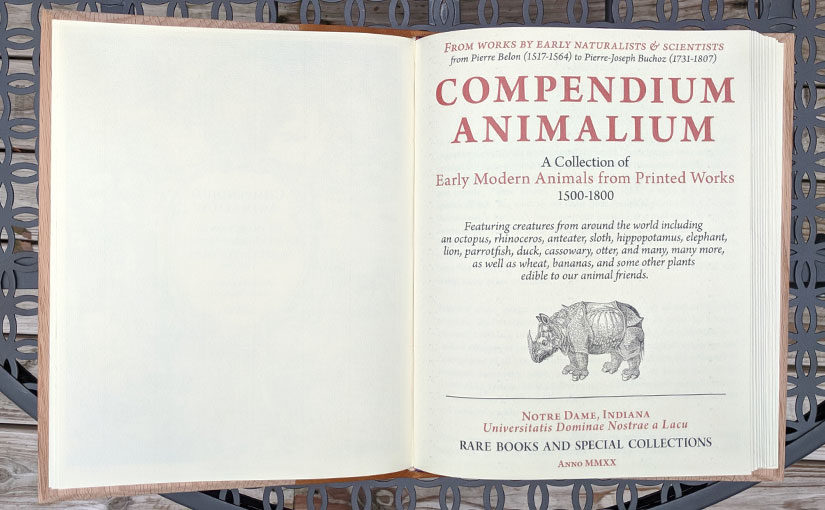

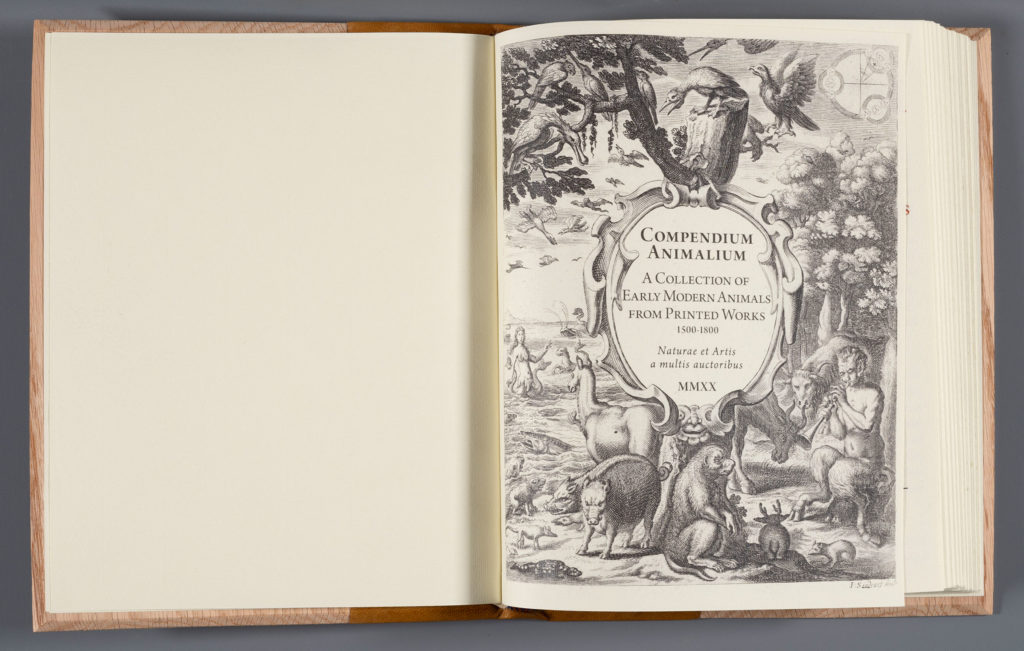

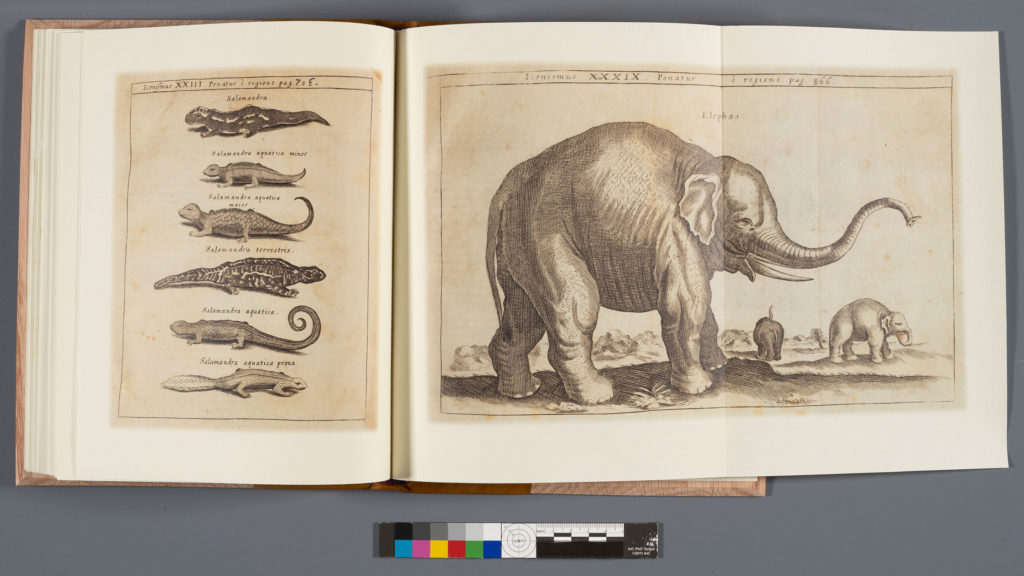

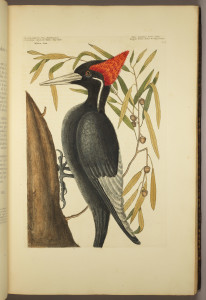

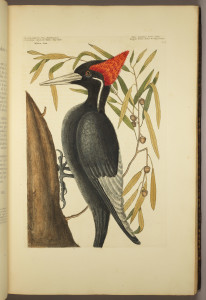

Another prominent collection is the Edward Lee Greene Collection related to natural science. This collection is formed from the personal library of Edward Lee Greene (1843-1915), an early botanist who researched and wrote about western American flora. His collection contains significant works from the sixteenth century, including the Herbarum uiuae eicones ad naturae imitationem (1532) by Otto Brunfels (1488-1534), who is regarded as one of the founders of botany. The collection also boasts Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1754), a stunning two-volume work with hand-colored plates. This book is of fundamental importance; it is the first publication devoted to the flora and fauna of North America. Along with the Greene Collection, ND Special Collections has holdings of over 4,000 works related to the history of science. Among these works are Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium celestium (1543), Galileo’s Dialogo (1632), and Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (1687).

Another prominent collection is the Edward Lee Greene Collection related to natural science. This collection is formed from the personal library of Edward Lee Greene (1843-1915), an early botanist who researched and wrote about western American flora. His collection contains significant works from the sixteenth century, including the Herbarum uiuae eicones ad naturae imitationem (1532) by Otto Brunfels (1488-1534), who is regarded as one of the founders of botany. The collection also boasts Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1754), a stunning two-volume work with hand-colored plates. This book is of fundamental importance; it is the first publication devoted to the flora and fauna of North America. Along with the Greene Collection, ND Special Collections has holdings of over 4,000 works related to the history of science. Among these works are Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium celestium (1543), Galileo’s Dialogo (1632), and Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (1687).

ND Special Collections has numerous other important literary and historical works including one of the most complete collections of the Nicaraguan writer, Ruben Dario, as well as extensive holdings of the works of Gabriela Mistral and Jorge Luis Borges. The collection of the American poet Robert Creeley (1926-2005) contains books not widely accessible to the public and the letters, reviews, and other pieces of ephemera the author placed inside his books, providing students and researchers a rare look into the poet’s private life.

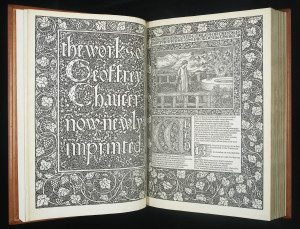

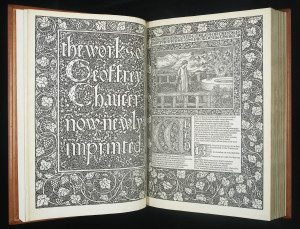

In addition to building collections that center around authors and content, ND Special Collections also collects books that are about the book itself. These include books issued from fine presses and books that push the boundaries of our general understanding of a book. The revival of fine press books can be traced to William Morris (1834-1896) and the press he founded, the Kelmscott Press, which printed books from 1890 to 1896. Morris was one of the leaders in the Arts and Craft Movement which developed in Britain and spread internationally between the mid eighteenth century and the early twentieth century. In reaction to the ill effects industrialization and capitalism had on printed books, Morris set forth to produce books that reclaimed the beauty and craftsmanship associated with the fifteenth century. He used only the finest materials–handmade paper, specially formulated ink, high-quality vellum–and the iron handpress to print limited editions of only a few hundred copies of the finest quality. Of the fifty-three works the press printed, the most celebrated and generally regarded as the finest work printed from a fine press is Morris’ The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted (1896). In addition to this fine work, ND Special Collections holds eleven other works issued from the Kelmscott Press.

Morris inspired others to establish fine presses. This trend spread across Britain, Europe, the United States, and continues today. Established in 1920 by Harold Midgley Taylor and taken over in 1924 by Robert Gibbings, the Golden Cockerel Press produced worked printed to the highest of standards and was noted for its woodcuts designed by notable artists such as Eric Gill. As Morris’ Chaucer was the Kelmscott’s finest work, Eric Gill’s Four Gospels (1931), part of the ND Special Collections Gill Collection, was the Golden Cockerel Press’ finest. In addition to works published by the Kelmscott Press and Golden Cockerell Press, ND Special Collections has collections from other notable fine presses including the Cuala Press, Stanbrook Abbey Press, Overbrook Press, Perishable Press, and St. Dominick’s Press.

Morris inspired others to establish fine presses. This trend spread across Britain, Europe, the United States, and continues today. Established in 1920 by Harold Midgley Taylor and taken over in 1924 by Robert Gibbings, the Golden Cockerel Press produced worked printed to the highest of standards and was noted for its woodcuts designed by notable artists such as Eric Gill. As Morris’ Chaucer was the Kelmscott’s finest work, Eric Gill’s Four Gospels (1931), part of the ND Special Collections Gill Collection, was the Golden Cockerel Press’ finest. In addition to works published by the Kelmscott Press and Golden Cockerell Press, ND Special Collections has collections from other notable fine presses including the Cuala Press, Stanbrook Abbey Press, Overbrook Press, Perishable Press, and St. Dominick’s Press.

Related to fine presses that produced limited editions of printed books using techniques that industrial presses could not produce is the development of artists books. What defines artists books is still in flux. To a large extent, they represent a work that is inspired by the function or structure of a traditional book; in some cases, the works resemble the common book with pages bound together and encased in a cover; in other cases, artists books look more like a sculpture or other work of art with very few characteristics of a traditional book. Artists books is a growing collection area for ND Special Collections. Our most extensive collection are works of the Ediciones Vigía in Matanzas, Cuba, founded in 1985, featuring handcrafted books of writers, musicians, and composers including Gabriela Mistral, Bob Marley, Jorge Luis Borges, and Gabriel García Márquez and designed by artists including Rolando Estévez. Artists books from the Ediciones Vigía are noted for their elaborate constructions with foldouts, jewelry, and shapes. Also in ND Special Collections is a collection of sixty-seven works from the Indiana University School of Fine Arts individual pieces from current books artists including Julie Chen, Karen Hamner, Jean-Pierre Hebert, Bill Kelly, among many others.