We join the Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month.

United Farm Workers

by Erika Hosselkus, Curator, Latin American Collections

The United Farm Workers, an organization with deep ties to the Mexican American community, came into existence in 1965, under the leadership of labor leader Cesar Chavez. It merged two existing groups of farm workers, one primarily Mexican and one primarily Filipino. Under Cesar Chavez’s leadership, United Farm Workers became a highly influential, multi-racial labor movement. It orchestrated the most successful consumer boycott in American history, against California grape producers, between 1965 and 1970. By allying with national and local unions and building boycott houses in 10 major cities, the UFW effectively shut down the U.S. market for grapes in protest over treatment of farmworkers. In July of 1970, after a final, failed attempt to offload rotting grapes in Europe, twenty-six grape growers capitulated and signed collective bargaining agreements with the UFW, a major victory for the country’s farm workers.

This post highlights some of Rare Books and Special Collections’ ephemeral material related to the history of the United Farm Workers organization, a beacon of Chicano strength and power.

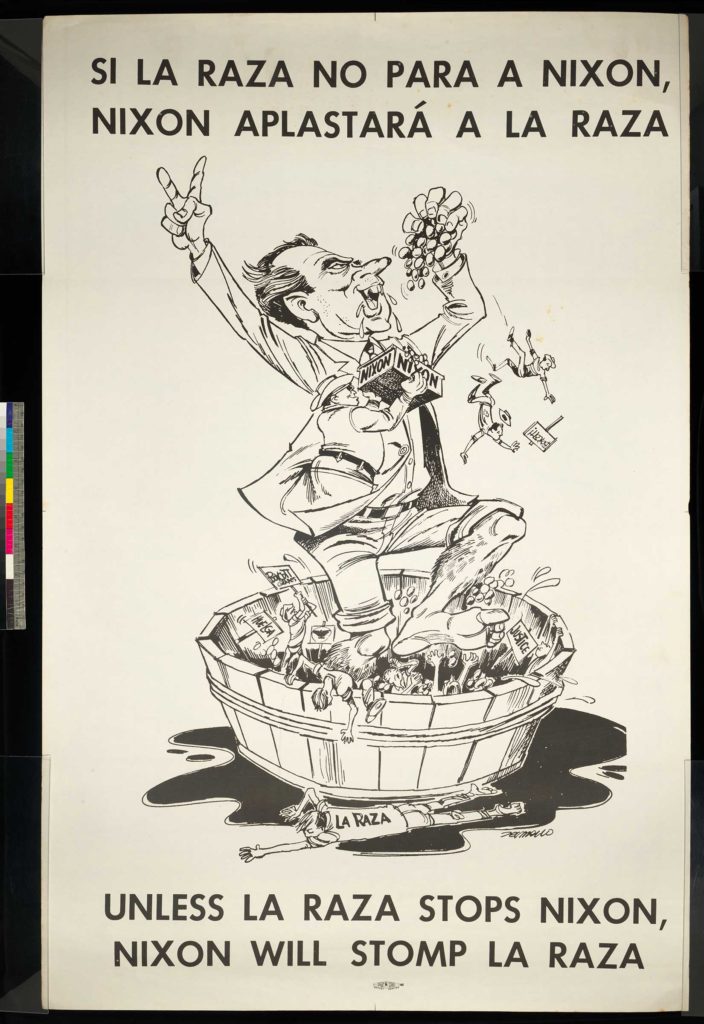

Andrew Zermeño, a graphic artist who created a number of political cartoons for United Farm Workers, produced this large bilingual poster in 1968. It connects the president-elect, Richard Nixon, to the abusive practices of California grape growers and warns that if “La Raza,” or the Mexican American population, doesn’t stop Nixon, he will stomp, or crush, them.

Portrayed in a grotesque fashion, Nixon waves his characteristic “V” for victory sign and greedily devours grapes. A grape grower is literally in Nixon’s pocket and farmworkers are crushed under his stomping feet. Small signs in Spanish and English refer to the boycott. A man representing La Raza lies inert in a pool of grape juice at the bottom of the poster.

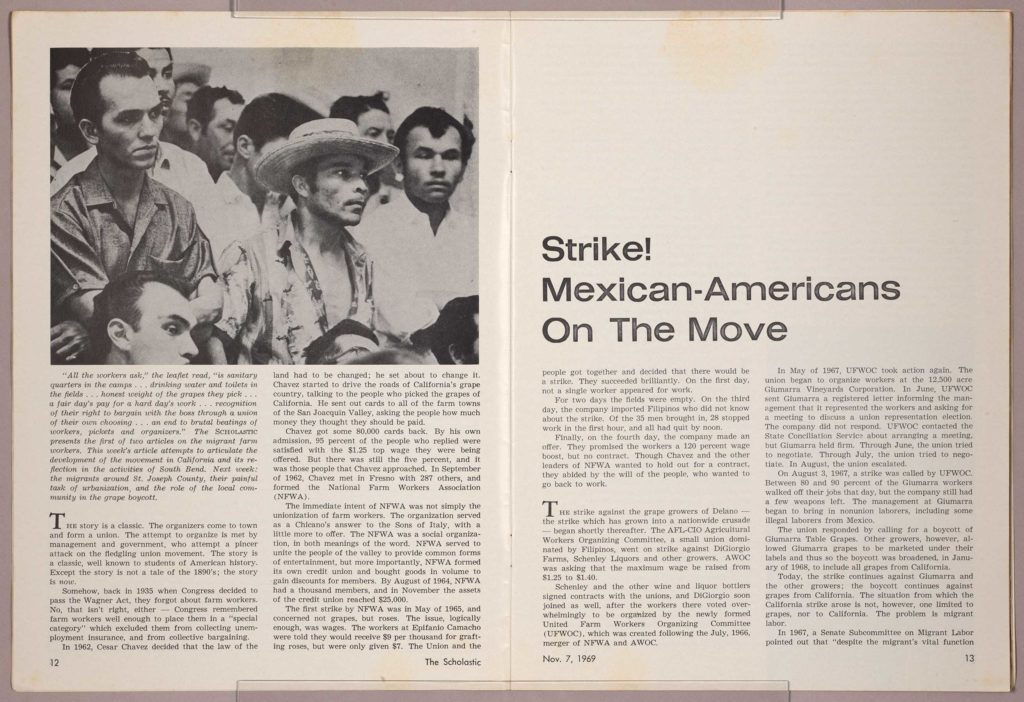

In 1969, the Scholastic, the University of Notre Dame’s student magazine, recognized the grape boycott. Its editors published the striking emblem of the Delano strike on the cover of the November 7 issue. Inside, the first of two articles on the farmworkers’ actions, authored by Steve Novak, describes the formation of the UFW and the history of the grape boycott. Novak observes that, “the Delano strike has done much for the Mexican-American people of the United States,” making them more visible, uniting them, and bringing their struggles to light.

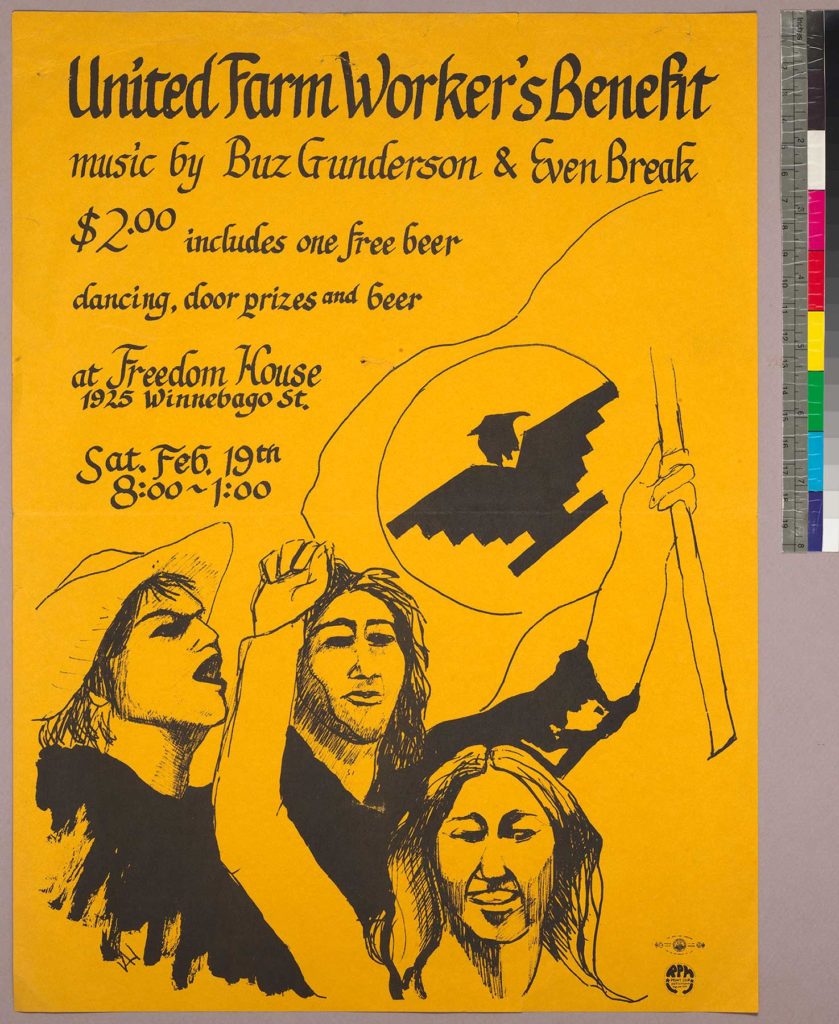

This final item is a modest poster promoting a United Farm Workers benefit held in Madison, Wisconsin, at Freedom House, a small venue. Likely also dating to the era of the grape boycott, the poster features the strike emblem and a group of three protestors, one with arm raised and one wearing a farm worker’s hat.

Together, these items reflect the national impact of the Delano grape strike. It spawned protest posters by Mexican American artists like Zermeño, merited a place on the cover of university student magazine in South Bend, Indiana, and prompted organization of a benefit in Madison, Wisconsin. The impact of this event was widespread and impressive, and it is an important part of the legacy of the U.S.’s Mexican American population.