If you have ever experienced a nasty scrape or burn, you know the process of healing is not very fun. Human skin can take several weeks to regenerate after an injury and that often comes with a fair amount of pain. For a bigger injury that involves tissue damage, there is often little the human body can do to regenerate larger parts. However, thanks to a small rodent – the African spiny mouse – regenerative medicine for humans could be making huge advances in the near future.

The concept of regeneration is not something new in the animal world – we have seen creatures like salamanders regenerate lost tails and starfish regrow lost limbs. However, the African spiny mouse is the only mammal ever observed to be able to completely regenerate tissue such as skin, fur, hair follicles, sweat glands, and even cartilage. Being able to quickly shed skin caught in the mouths of large predators comes in handy for the mouse to be able to escape, but they must also be able to quickly heal those wounds.

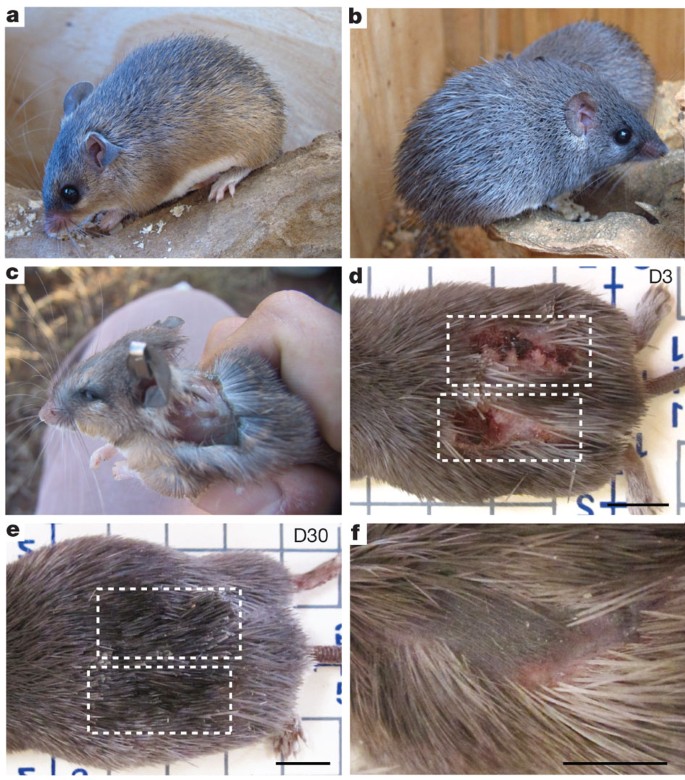

How exactly does this happen? Researchers have found that the skin of the spiny mice is much weaker than that of most other mammals – think 20 times weaker than the skin of your regular old house mouse. Upon being handled, the skin is quick to shed leaving gaping wounds across the backs of these mice. This is due to the density of hair follicles found in their skin – a greater proportion of follicles means there is much less connective tissue to hold the skin leading to very easy tears. The weakness of the skin is contrasted by the rapidity by which it heals – the wounds can shrink to two thirds of their original size in a single day!

To understand a little bit more about the biomechanics of this process, we must look at how exactly the skin heals. As it turns out, collagen, the structural protein found in tissues which is responsible for skin elasticity among other things, is partly responsible for this phenomenon. Whereas mammals like you and I heal injuries through the generation of dense layers of collagen fibers aligned in parallel layers, these mice produce collagen fibers in crisscross networks that resemble the original makeup of tissue. This leaves the healed skin completely scar-free.

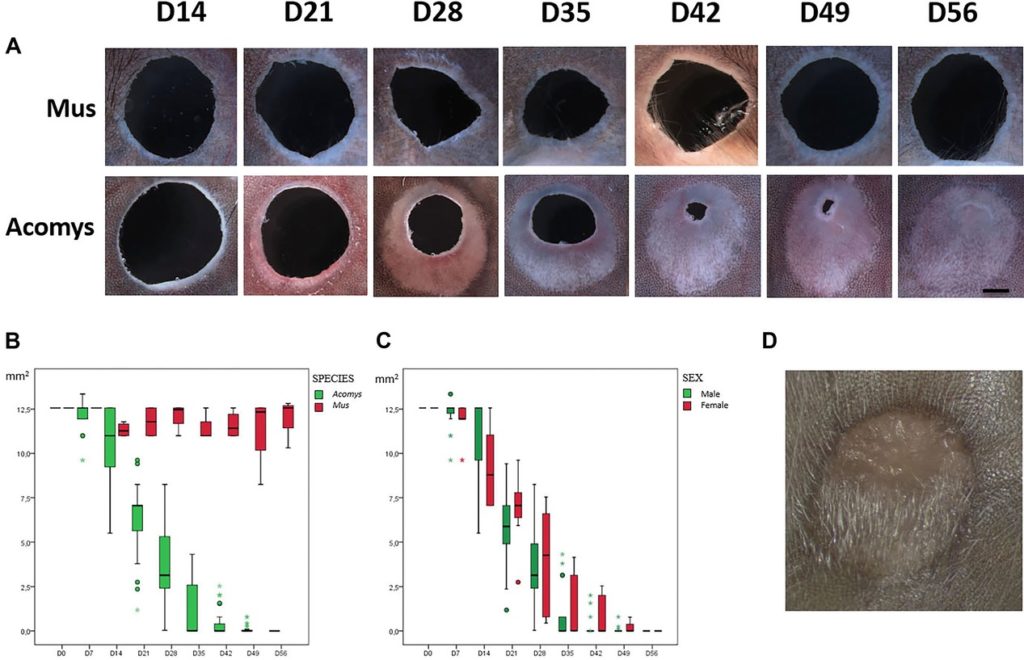

In addition, researchers have noted that ear wounds in the mice heal in a way similar to salamander tail regeneration. When a mouse’s ear gets injured, a ball of cells forms at the site of the wound that resembles cells in the embryonic state. This cell clump, called a blastema, is what allows the lost tissue to regrow on the ear. Scientists hope to use this information to study regeneration of tissue in humans.

While there is still more research to do on the healing mechanism of the spiny mice tissue, the research done on these little mammals provides an excellent foundation for regenerative medicine for humans – something that studying regeneration in other animal species has not been able to accomplish. Being able to regenerate a lost limb was something once found only in science-fiction but could be a real possibility in the future.

Read More:

Insights into the regeneration of skin from Acomys, the spiny mouse

African spiny mice can regrow lost skin

Featured image modified from “Spiny Pocket Mouse” which is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.