Rock climbing may just be the greatest exercise activity. It’s a holistic workout with an infectiously supportive community that involves plenty of problem solving and a good understanding of body movement and biomechanics. If you ever find yourself on the climbing wall, you will inevitably encounter a sequence of moves that seemingly proves to be too difficult or complicated. Whether you’re a veteran or a beginner, below are just a few of the countless biomechanical techniques and tips to keep in mind when coordinating and executing your attempts; they could be the difference between plateauing and finally topping out on that elusive route.

Grip Type (Open vs. Closed)

In general, you can grip a hold in either of two ways: open or closed. The open grip (left) is what you would use for most of the holds you grab onto along a route. However, when you encounter certain holds like crimps—small holds with minimal edge lengths—you might be forced to utilize the closed grip position (right). Where the open grip stresses the forearms, the closed grip stresses the bones of the fingers and especially the tendon pulleys that run along them. The best climbers are capable of employing the closed grip, but know to do so only when necessary; they work on their forearm muscles by open gripping most holds and save themselves from joint and tendon pulley injuries.

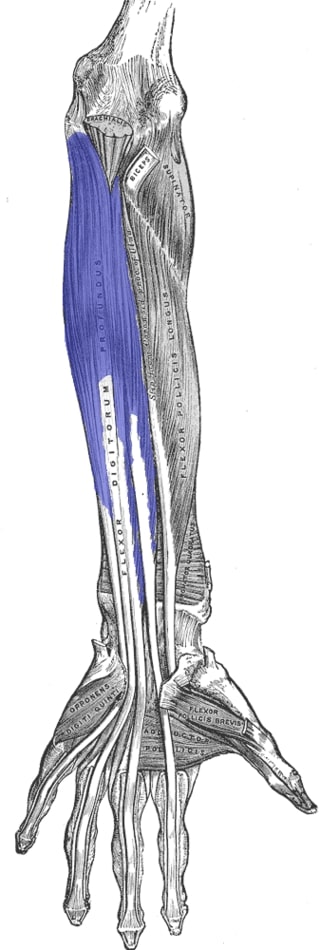

Quadriga Effect

The quadriga effect explains why the force applicable by a finger is dependent on how curled or straight the other fingers are. While each of the middle, ring, and little fingers has their own flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon, these tendons coalesce into a common muscle belly in the forearm (as shown to the right). As a result, if one or more of these fingers is straightened and held stiff while you try to reach full excursion (curling) with the others, you will be unsuccessful in curling that distal finger joint. It’s important to understand this phenomenon as a climber because when you have to pull on a hold with just one, two, or three fingers, it’s beneficial to know that curling the fingers that aren’t engaged in contact will contribute to a stronger grip. Check out this video for a great explanation and demonstration.

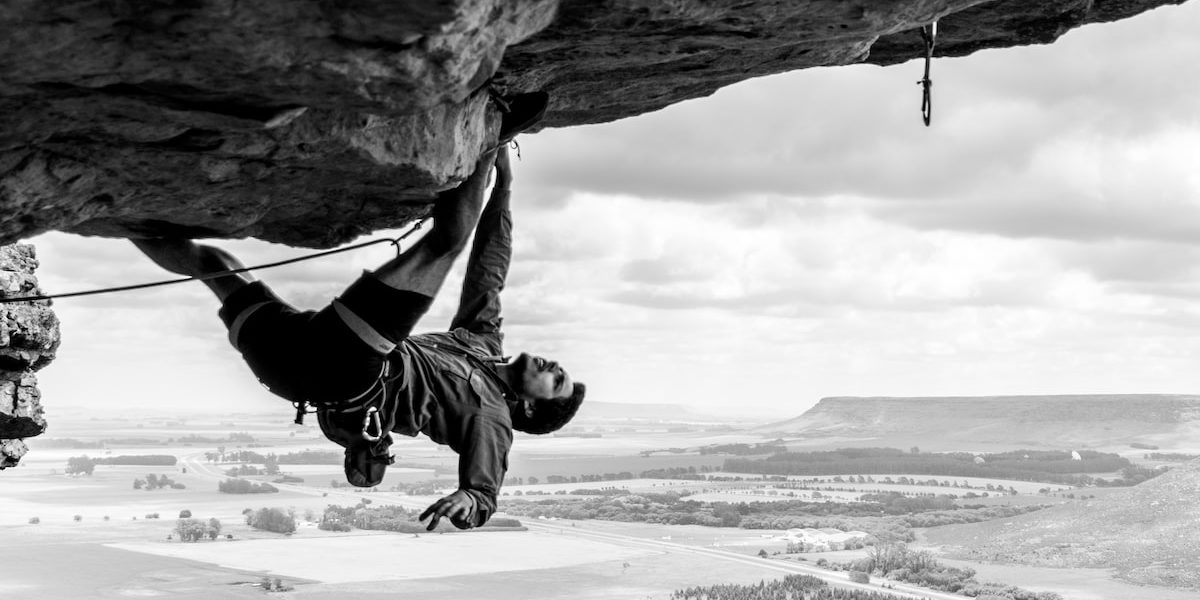

Hug that Wall

Bringing your center of gravity closer to the wall decreases the force demanded from your arms to refute the moment created by your trunk about the footholds at the wall. Moving your trunk closer to the wall, more above your feet, shifts more of the weight bearing role to your legs—which are much stronger than your arms and are built to endure more weight. Applying this technique throughout longer climbs is especially important because it saves your arms from getting gassed too early.

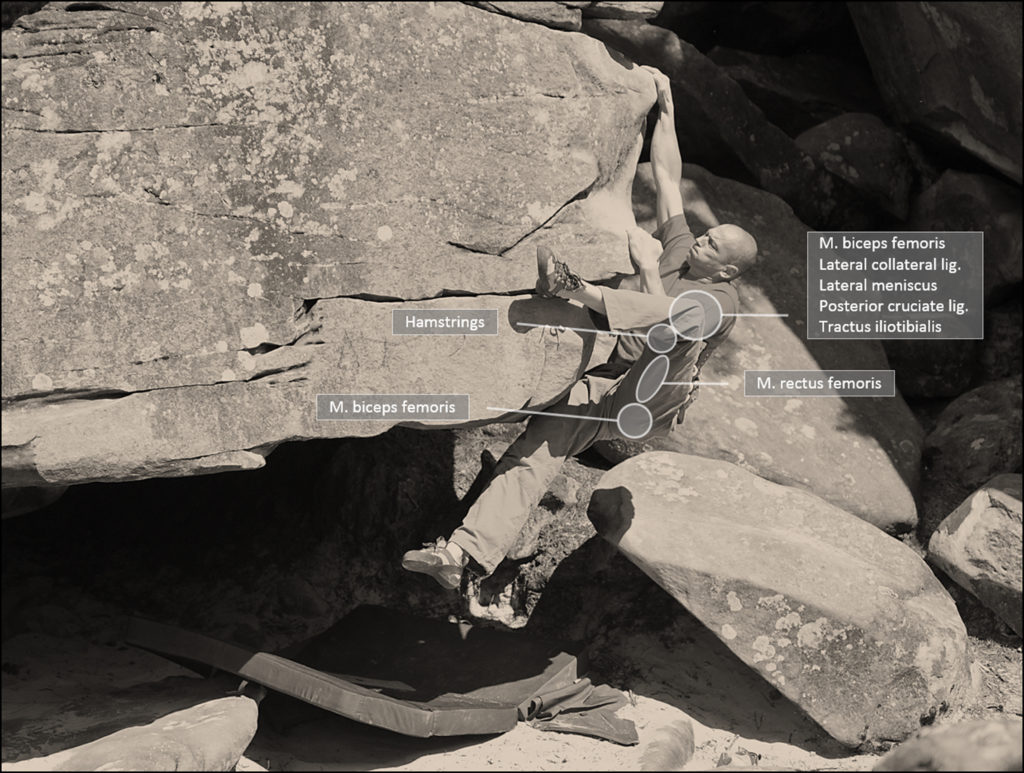

Heel Hook

Your feet aren’t only useful for standing on; they can also be used to hold tension to free up a hand for a movement or even to pull you up. To employ this maneuver, place your heel at the desired location and dig it into the hold by pulling with your hamstrings. The climber in the image to the left is placing his left heel on top of a ledge even with his head, preparing to pull himself up with his left hamstring and right arm; because he has secured the left side of his body with a heel hook, he has freed up his left arm to extend to the next hold.

These, again, are only a few of many tricks to try while climbing. If you are curious about even more technique tips, read on here.