When we think about reading, we usually imagine reading silently to ourselves—unless we’re reading to children, or sharing an especially funny or interesting blog post with a friend! (Feel free to do this). But in the early medieval period, the reverse held true: oral reading was more common than silent reading. For example, in Augustine’s Confessions, Augustine visits his friend and mentor Ambrose, and is surprised by Ambrose’s eccentric habit of reading silently:

“When he read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely, and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud” (Confessions [Paris, 1959], 6.3).

Oral reading was a public, social event. One person would read aloud to the group, and the group could give him or her feedback, comment on the text, and discuss afterwards.

In the twelfth century, however, reading practices started to change. Silent reading became more popular, eventually becoming the most common way of reading in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

As a private, portable experience, silent reading opened a whole new kind of learning. You could now learn on your own, without hearing others’ feedback or criticism. You could spend as long as you wanted on a particular section and re-read it as often as you wanted. You could have two manuscripts in front of you and cross-reference them, or check the citations in one manuscript against a copy of the cited text.

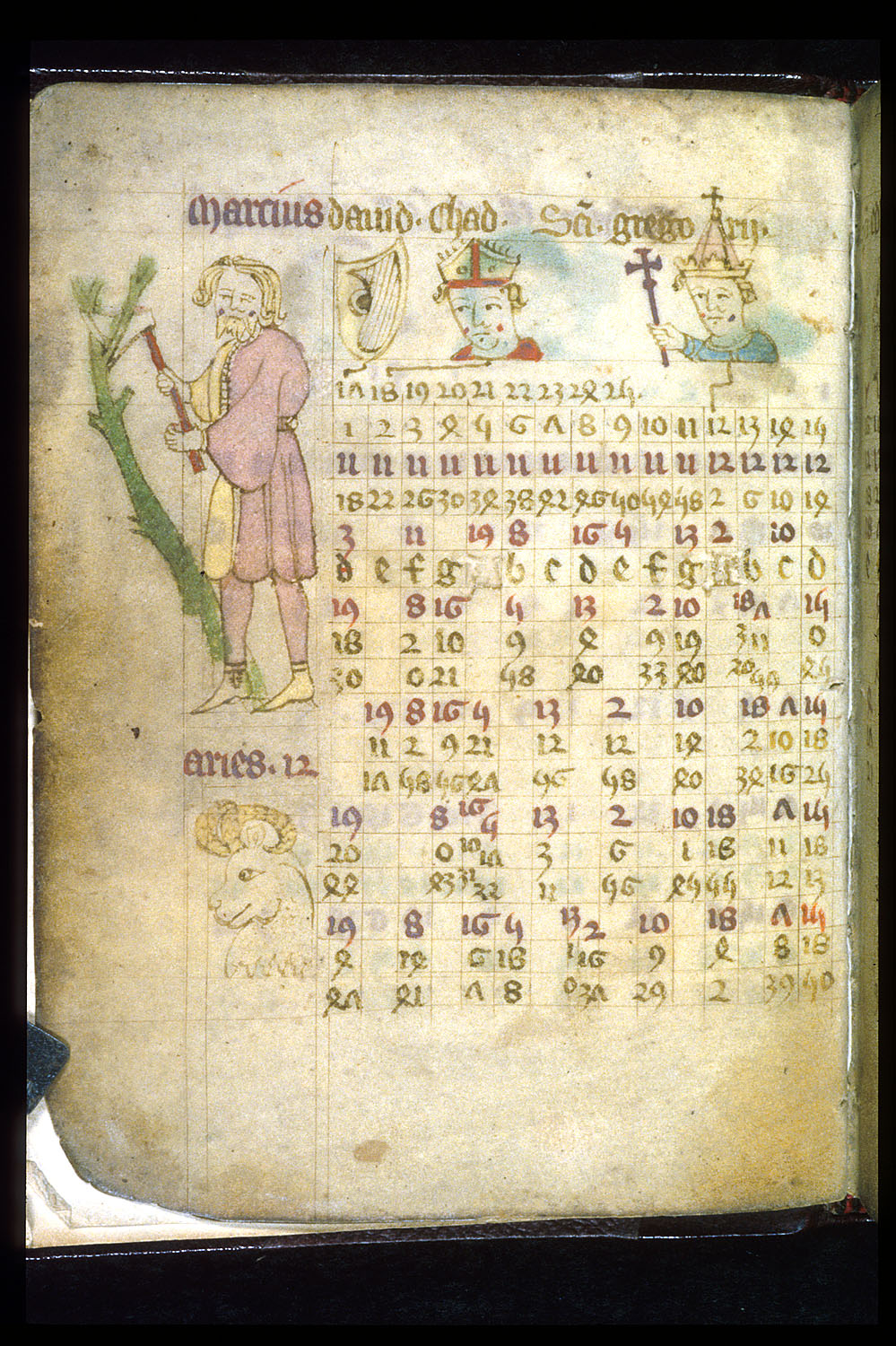

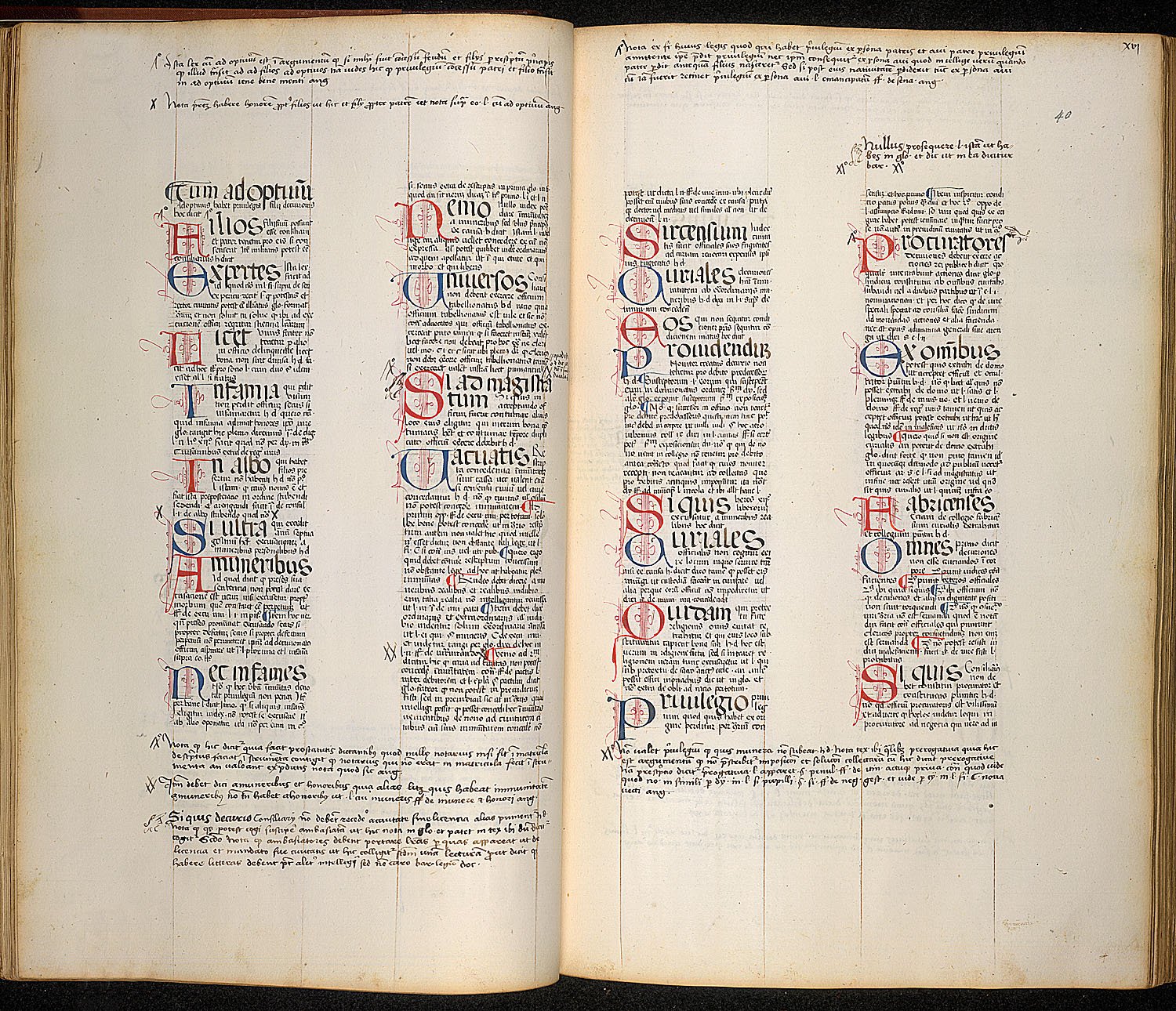

Silent reading influenced the way manuscripts were arranged. Because texts were read visually, not heard, manuscripts frequently included a table of contents, subheadings, and other similar organizational markers (ordinatio). The new interest in structure and cross-referencing helped shape scholastic writings. Scholastic authors wrote (in)famously dense, complex works for an audience that could re-read long sentences and check manuscripts against each other.

Silent reading also contributed to heterodoxy—private readers could access heretical works without the censorship or criticism that might take place in a group reading. Similarly, private reading triggered a small revival in fifteenth-century French pornographic manuscripts. (Imagine trying to read a medieval Shades of Grey in front of a group!)

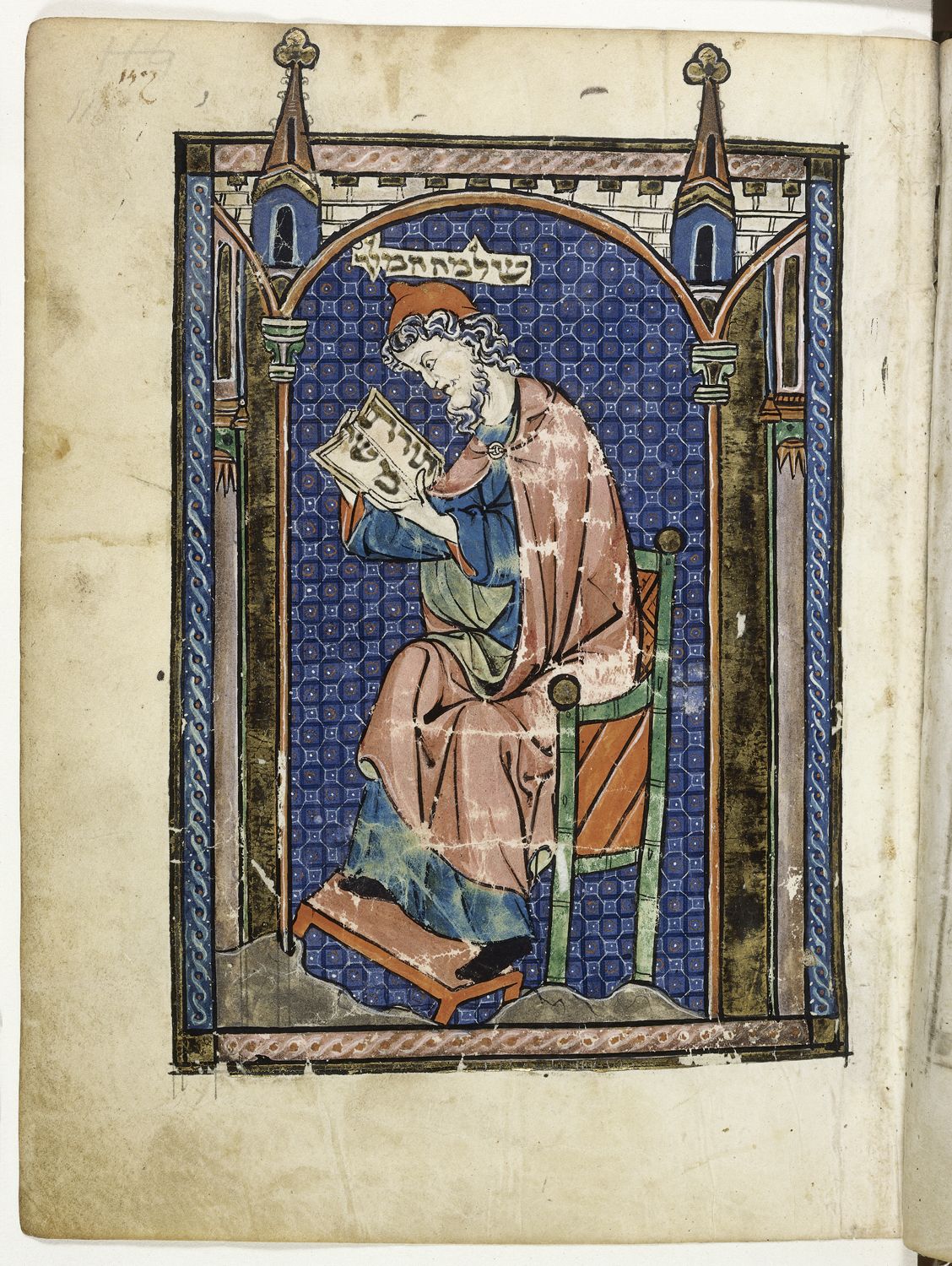

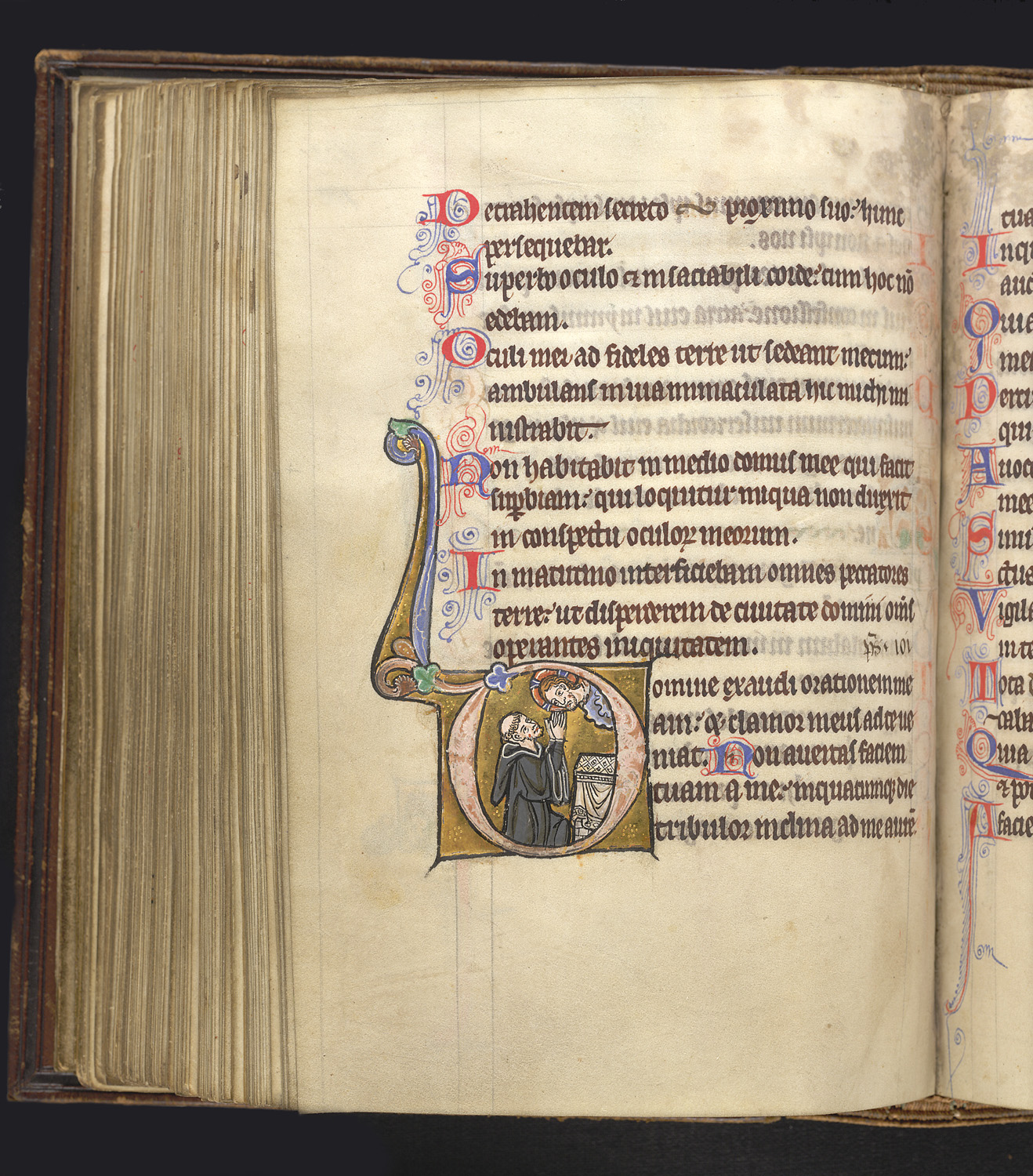

The privacy of silent reading also transformed devotional and spiritual experiences. It allowed the reader’s mind to briefly wander but return to the spiritual texts, discovering the hidden and mystical meanings in an intensely personal way. Monastic orders in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries emphasized silent contemplation and meditation which began with private reading. These new practices contributed to new ways of thinking about the self and one’s relationship to God, ideas that culminated in the Protestant Reformation.

While oral reading never really disappeared, the medieval rise of silent reading transformed reading and devotional practices. Ultimately, it contributed to modern ways of thinking about God, the community, and the self.

Caitlin Smith

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of our ongoing series on Multimedia Reading Practices and Marginalia: Medieval and Early Modern.