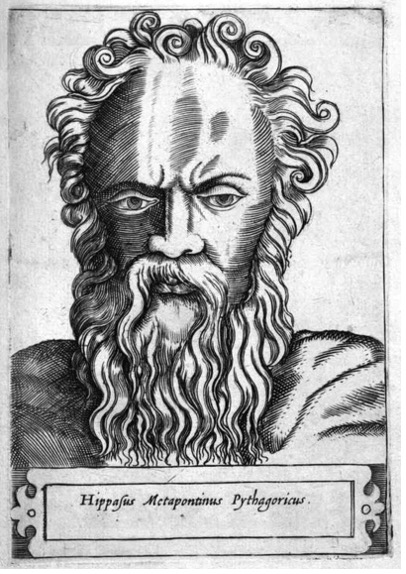

Legend has it that Pythagoras sentenced the first person to discover irrational numbers, Hippasus of Metapontum (c.530-450 BC), to death. He was tossed overboard a ship to drown. Why? Pythagoras taught that number was the essence and cause of all things, and for Pythagoras and his followers, numbers meant integers. Hippasus’ discovery of irrational numbers appeared to undermine the very core of Pythagoras’ teachings about the numerical nature of the universe. The secret could not get out. Hippasus had to die.

The existence of irrational numbers became a Pythagorean secret. They were called “unutterables” because in Greek, the ratio between two integers was called logos, and so, irrational numbers were called, alogos, which can be translated as either “irrational” or “not spoken.” The worry caused by this secret knowledge was somewhat alleviated by Eudoxus of Cnidos (408-355 BC) when he argued that the basis of reality was a ratio of magnitudes. In effect, Eudoxus made geometry replace arithmetic as the highest mathematical discipline, the foundation of all others. Geometry and arithmetic were hardly even separate disciplines at the time. This change of emphasis allowed Pythagorean teachings about the numeric nature of the universe to continue.

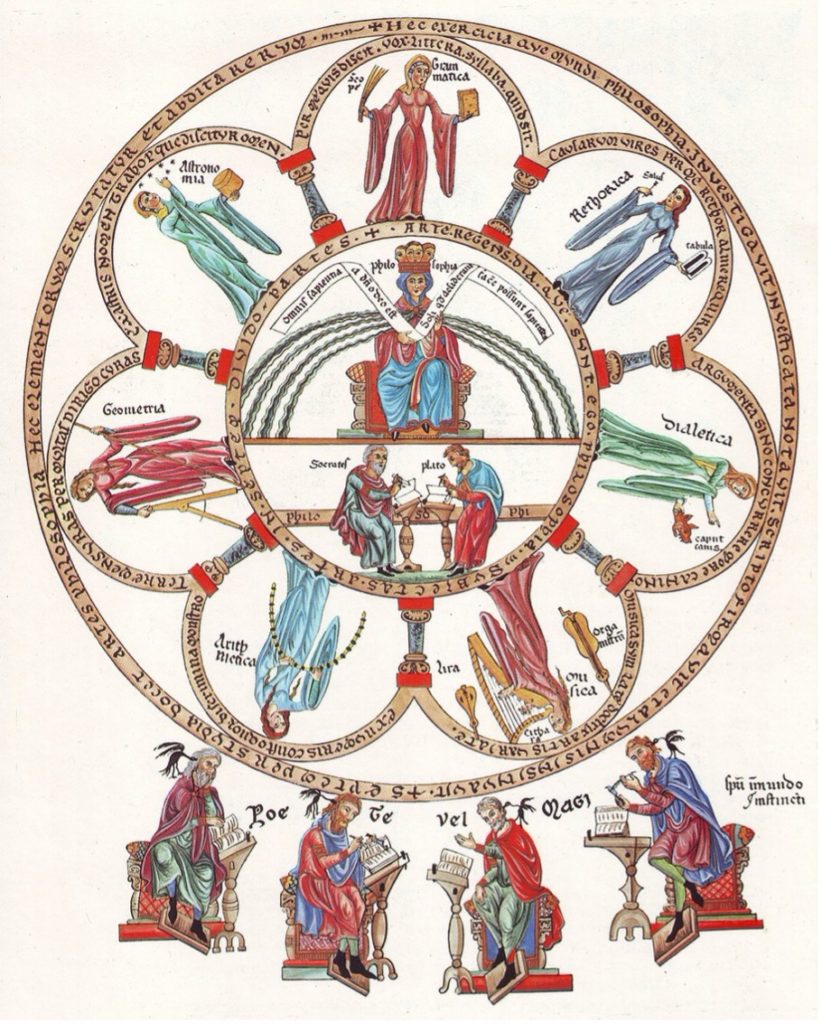

The idea that the mathematical disciplines have some orderly relationship between each other is essential for understanding the medieval concept of “quadrivium.” While it is well known that the medieval liberal arts curriculum, at least in its ideal established by Boethius, taught that a student must study both the trivium and quadrivium before progressing to philosophy and theology, the exact nature and rationale for the quadrivium is often less understood. Lists of the arts comprising the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music/harmony) are consistent, but the exact order for these lists can vary. While there is no doubt that sometimes there is truly no rationale for a given order of the mathematical arts, attention to the mathematical art considered the principle or highest can reveal at least three identifiable streams of quadrivial traditions coming from the ancient world (similar to Chenu’s identification of different kinds of Platonism): the Boethian, the Calcidean, and the Capellan. The mathematical art considered “principle” is the one closest to metaphysical reality of the universe and serves as the foundation for all other mathematical disciplines. While the problem of irrational numbers may not have been on the forefront of anyone’s mind in the Middle Ages…it was a closely guarded Pythagorean secret after all…the problem of the principle mathematical art, inherited from Pythagoreanism, was readily available in the source texts.

Boethius (c.480-525) not only established the seven liberal arts as the traditional curriculum for the Middle Ages, but he also wrote treatises on all of the trivium as well as arithmetic, music, and geometry (the latter work is now lost). He, coined the term, “quadrivium” in his attempt to translate the tessares methodoi (four methods) of the Neopythagorean, Nicomachus of Gerasa (c.60-120). Boethius’ own De institutione arithmetica largely draws upon the work of Nicomachus. Modern day history of mathematics textbooks often observe that Nicomachus’ work is one of the first to distinguish arithmetic and geometry as separate disciplines but that the actual quality of the mathematics contains basic errors. Unlike Euclid, Nicomachus doesn’t always give his proofs. Nicomachus presents arithmetic as the principle mathematical art and as a result, so does Boethius. While Boethius was unlikely to have gotten the problem of irrational numbers from Nicomachus because Nicomachus presents arithmetic as the highest mathematical art, Boethius adopts his fourfold division of the mathematical arts along with the belief that arithmetic was the principle mathematical art (De institutio arithmetica 1,1,8).

In his work on arithmetic, Boethius explains that the order of the quadrivium he offers (music, astronomy, geometry, and arithmetic) both reflects the true nature of the universe and is the proper pedagogical order for the study of mathematics as a preparation for philosophy. Progression through each of the arts trains the mind to move from sense perception to intelligible reality.

This progression of the soul can be seen in the Consolation of Philosophy, where Boethius begins with music and is drawn to philosophy upward by means of astronomy, geometry, and finally arithmetic.

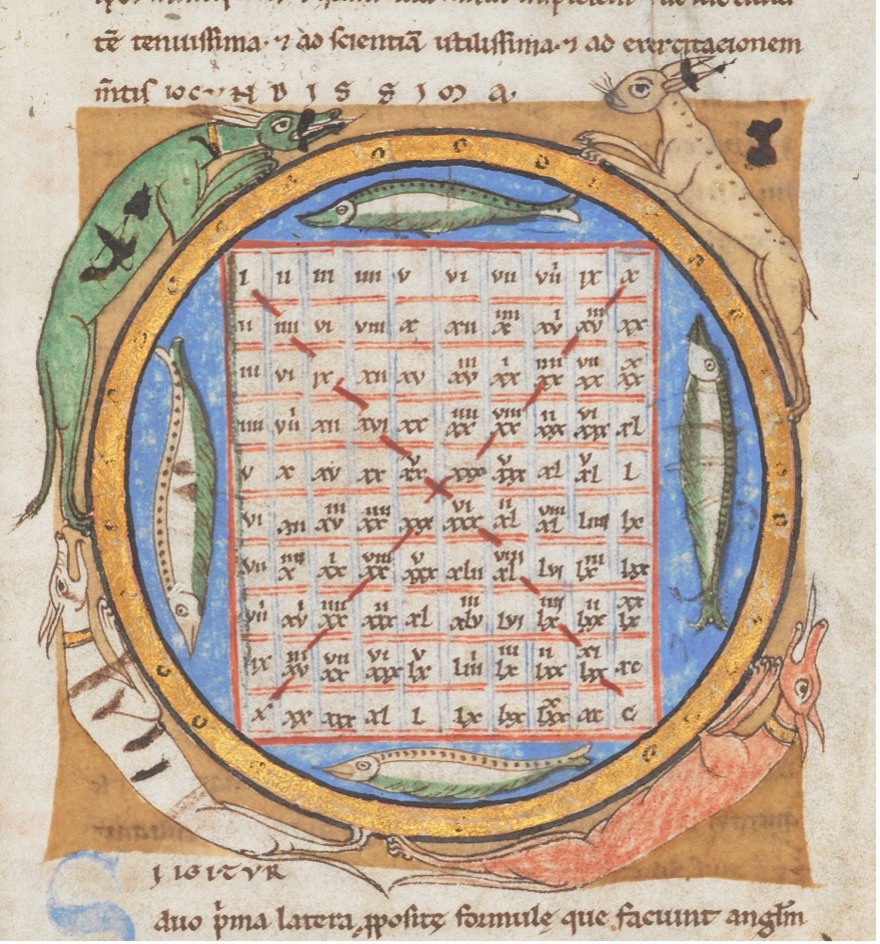

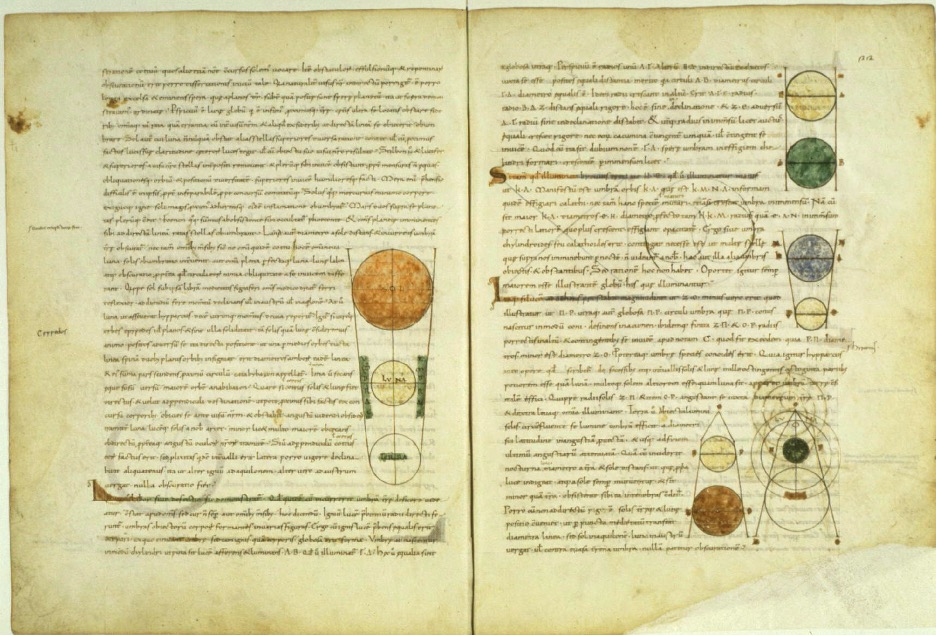

While Boethius’ highly influential order of the quadrivium was adopted by both Cassiodorus and Isidore, Calcidiuswrites very clearly in his commentary on Plato’s Timaeus that geometry is the foundation of all other mathematical arts (Commentum 2.32). His influence throughout the Middle Ages was also extensive. Calcidius’ translation and commentary of Plato’s Timaeus, was one of the only texts of Plato available throughout much of the Middle Ages. Although there were other translations of the Timaeus available, Calcidius’ commentary, as Reydams-Schils has demonstrated, was actually a very good introduction to Platonism as a whole because it was designed to introduce the reader to Platonic doctrine in a pedagogically sequenced way from mathematics to physics and then theology. Throughout the earlier Middle Ages, as Somfai has shown, the commentary was used to teach the quadrivium itself, and earlier versions contained numerous geometrical diagrams. While interest in his geometrical figures appears to fall out of favor in the twelfth century and in newer commentaries on the Timaeus, Nicholas of Cusa in the fourteenth century has both the old Calcidius’ commentaries and the newer commentaries, and geometry clearly plays a major role in his understanding of infinity and kinds of infinity.

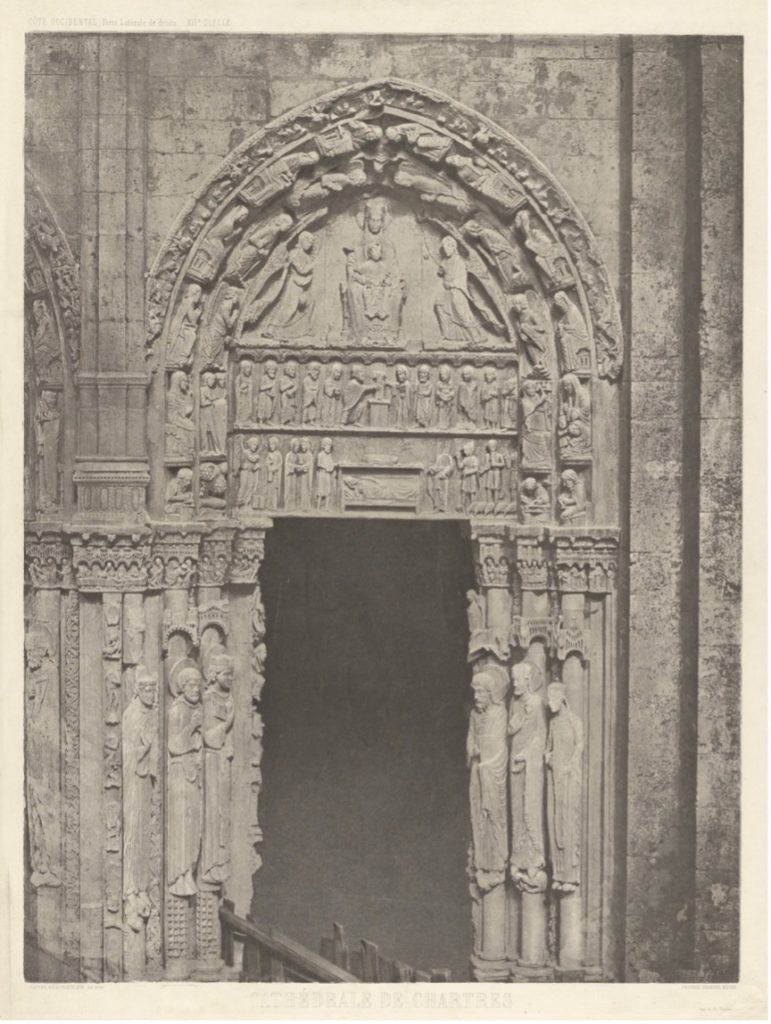

The third line of quadrivial tradition can be found in Martianus Capella whose Marriage of Philology and Mercury, places music as the highest of the seven liberal arts, the culmination of his entire work. As Michael Masi has observed, this ordering can be found in many visual depictions of the quadrivium, including most famously, the Incarnation Portal at Chartres Cathedral, where arithmetic is paired with geometry as a mathematical study and music with astronomy as a study in harmony. While the complete reasons for this preference are too numerous to identify in a blog, there is a certain kind of Pythagorean logic even here. Music, for Pythagoras and his followers, was thought to be the best evidence for number being at the foundation of the universe. Even the movement of the stars and planets were considered to be one example of many kinds of music in the universe.

The stakes for getting the order of the quadrivium right in the Middle Ages may not have risen to the level of murder (although that might make a nice monastic murder mystery written by Umberto Eco, Murder Most Irrational….). And yet, three sources for the quadrivial tradition in the Middle Ages did present the idea that the order of the mathematical arts reflects the most fundamental nature of the universe itself. Furthermore, this fundamental order of the universe has implications for the order of education in the mathematical arts. These stakes, the metaphysical order of the universe and of education, would still have been considered pretty high for most thinkers throughout the Middle Ages.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams is a Professor for Memoria College’s Masters of Arts in Great Books program and graduated with her doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute in 2012. She was also the founding director Liberal Arts Guild at LeTourneau University. Her research focuses upon twelfth-century Platonism and poetry, especially Thierry of Chartres and Bernard Silvestris.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading:

Albertson, David. Mathematical Theologies: Nicholas of Cusa and the Legacy of Thierry of Chartres. Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199989737.001.0001.

Boethius. Boethian Number Theory: A Translation of the “De Institutione Arithmetica” with Introduction and Notes. Translated by Michael Masi. Studies in Classical Antiquity; v. 6. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1983.

Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by Victor Watts. London: Penguin, 1999.

Burton, David M. The History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 1988.

Caiazzo, Irene. “Teaching the Quadrivium in the Twelfth-Century Schools.” In A Companion to Twelfth-Century Schools, edited by Cédric Giraud, translated by Ignacio Duran, 88:180–202. Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition. Brill, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004410138_010.

Calcidius. On Plato’s Timaeus. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 41. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Chenu, M. D. Nature, Man, and Society in the Twelfth Century: Essays on New Theological Perspectives in the Latin West. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

Eco, Umberto. The Name of The Rose. Reprint edition. Boston: HarperVia, 2014.

Evans, Gillian R. “The Influence of Quadrivium Studies in the Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Schools.” Journal of Medieval History 1, no. 2 (July 1975): 151–64.

Fassler, Margot E. The Virgin of Chartres: Making History through Liturgy and the Arts. Yale University Press, 2010.

Fournier, Michael. “Boethius and the Consolation of the Quadrivium.” Medievalia et Humanistica, no. 34 (2008): 1–21.

Gersh, Stephen. Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism: The Latin Tradition. 2 vols. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1986.

Martianus Capella. Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts. Translated by William Harris Stahl, Richard Johnson, and E.L. Burge. Vol. II: The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. 2 vols. Records of Western Civilization 84. Columbia University Press, 1992.

Masi, Michael. “Boethius and the Iconography of the Liberal Arts.” Latomus 33, no. 1 (January 1, 1974): 57–75.

Nicholas of Cusa. Nicholas of Cusa on Learned Ignorance: A Translation and an Appraisal of De Docta Ignorantia. Edited by Jasper Hopkins. Minneapolis: The Arthur Banning Press, 1985.

Oosterhoff, Richard. Making Mathematical Culture: University and Print in the Circle of Lefèvre d’Étaples. Oxford-Warburg Studies. Oxford: University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198823520.001.0001.

Reydam-Schils, Gretchen. “Meta-Discourse: Plato’s Timaeus According to Calcidius.” Phronesis 52 (2007): 301–27.

Somfai, Anna. “Calcidius’ Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus and Its Place in the Commentary Tradition: The Concept of Analogia in Text and Diagrams.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 47, no. Supplement_83_Part_1 (January 1, 2004): 203–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-5370.2004.tb02303.x.

Somfai, Anna. “The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato’s Timaeus and Calcidius’ Commentary.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65 (2002): 1–21.

Stahl, William H. “The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella: Its Place in the Intellectual History of Western Europe.” In Arts libéraux et philosophie au moyen âge, 959–67. Actes du IVe Congrès internationl de philosophie médiévale. Montreal Paris, 1969.

Stahl, William Harris, Richard Johnson, and E.L. Burge. Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts. Vol. I: The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella. 2 vols. Records of Civilization, Sources and Studies 84. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.