American mythology is filled with larger-than-life figures, like the axe-wielding Paul Bunyan and the rattlesnake-handling Buffalo Bill. Some of them are historical or pseudo-historical, such as Davy Crocket and Daniel Boone (who both famously die in the Alamo siege during the Texas revolution). Of course, there is little ground more fertile for American mythology than the colonial and revolutionary historical periods, with George Washington’s cherry tree and Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride to alert colonists in Lexington and Concord of the British army’s approach. Both of my latter examples demonstrate how historical figures are imagined and reimagined by subsequent generations of Americans, considering that Washington probably never actually chopped his cherry tree, nor did Paul Revere quite make it to Lexington or Concord to warn that the redcoats were coming toward the rebel munitions stored there. Indeed, all of the aforementioned mythic American figures and stories are somewhat less invested in historical fact and more in the self-fashioning of a European ethnonationalist identity in the United States.

In early America as elsewhere, storytellers and mythographers, such as Washington Irving (who famously wrote “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” about a little haunted town in New York), begin not only looking to the colonial period but also across the pond to European ethnonationalist antiquarianism in the construction of distinctly American mythology following a successful revolutionary war overthrowing the British government. This is observable in another of Irving’s works, “Rip Van Winkle” which tells the tale of a man who meets with a dwarvish fairy in the Catskill Mountains and falls magically asleep for the bulk of his life, only to awaken as an old man and find his children grown. This fantastic story brings early medieval fairy lore—elves, dwarves and the like—into the American frontier and invites these supernatural beings from the “old world” into the newly formed United States.

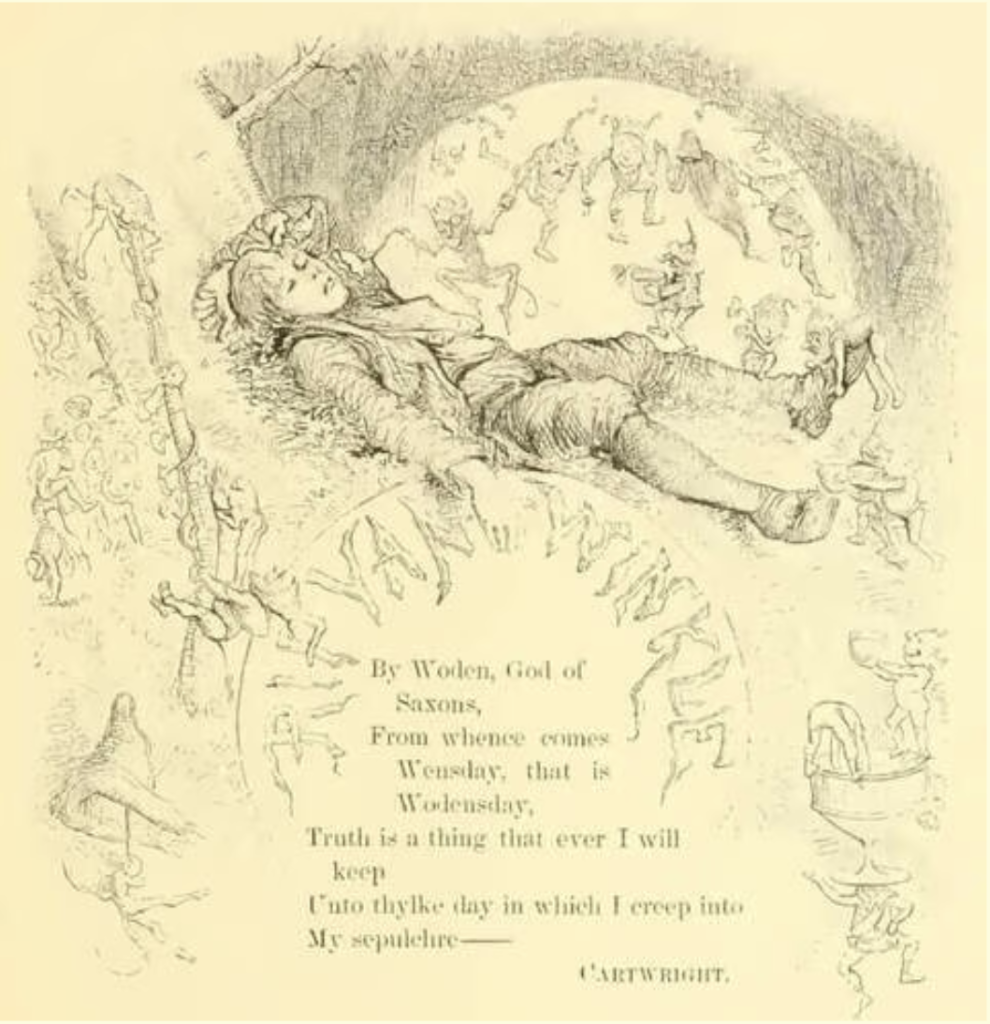

The story begins with an explicit epitaph from the tomb of one Diedrich Knickerbocker that invokes the pre-Christian Germanic mythic figure “Woden, God of Saxons” (1):

By Woden, God of Saxons,

(Irving , “Rip Van Winkle” 1-5).

From whence comes Wensday, that is Wodensday,

Truth is a thing that ever I will keep

Unto thylke day in which I creep into

My sepulchre

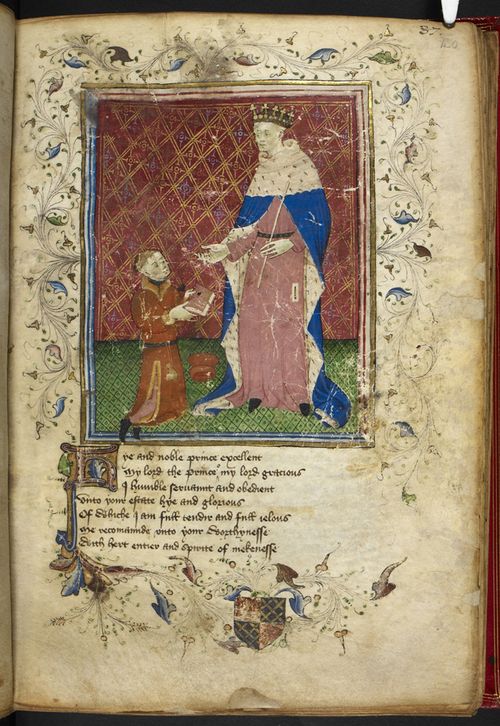

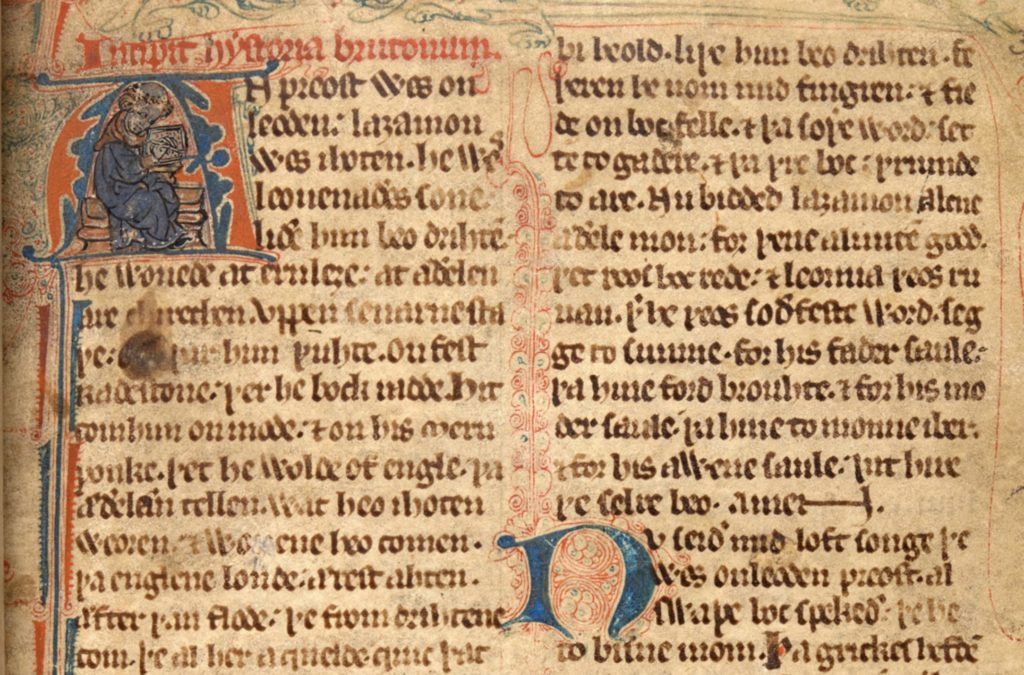

In order to grow, myths need both substance and storyteller—in other words both the story itself and persons to pass the tale along to others. The art of storytelling and oral narratives are seemingly as old as humankind, but storytelling as a pastime is regularly associated with the medieval period, made famous by late medieval works of literature such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Indeed, in the tradition of English literature, Chaucer’s work looms large, and has inspired numerous imitators and allusions even in recent years.

Margaret Atwood’s book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), follows in this tradition, and her novel’s name serves both as a pejorative toward the historical period—suggesting the future could go backwards in time in terms of social progress with respect to religiosity, intellectual freedom and gender equality—and as a simultaneous homage to the literary influence of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Atwood, whose novel is understood by the reader to be an academic transcription of a personal diary, logged on a voice recorder and being discussed centuries later after the log is transcribed and analyzed by a scholar who gives the book its editorial title included in the back “Historical Notes” section of the book:

“The superscription ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ was appended to it by Professor Wade, partly in homage to the great Geoffrey Chaucer…I am sure all puns were intentional, particularly that having to do with the archaic vulgar signification of the word tail…”

(Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale 300-301).

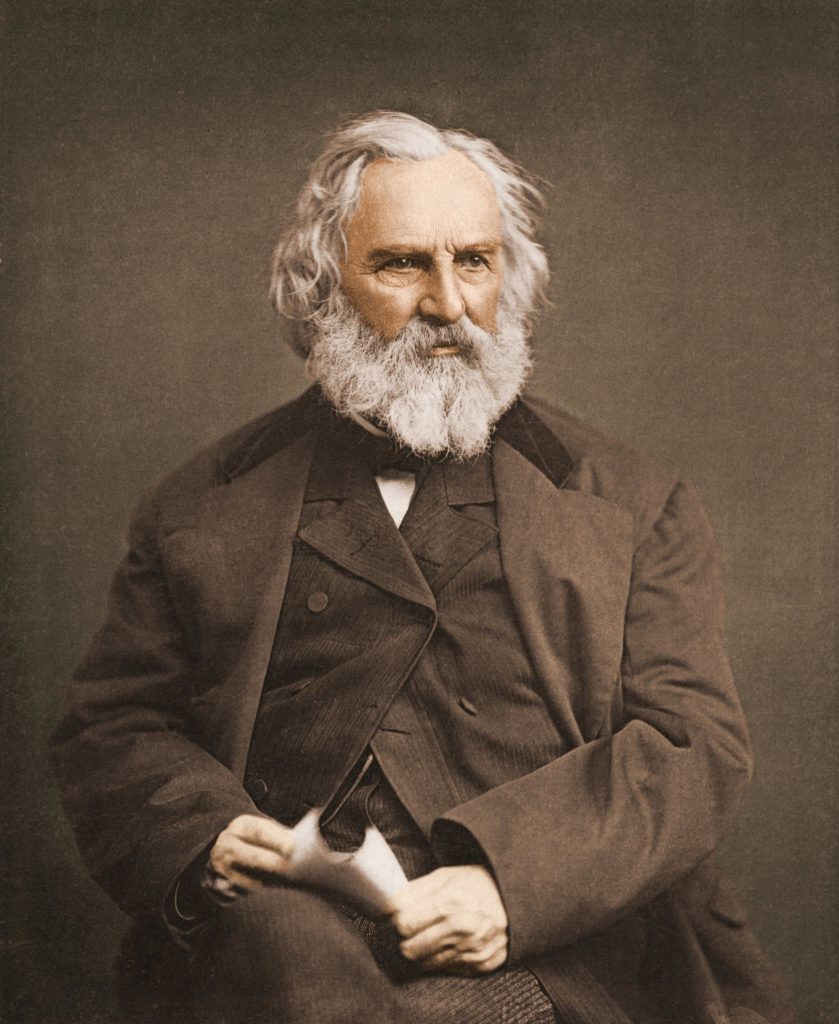

Similarly, Harvard professor and early American poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, follows Chaucer’s model in his collection of poems, Tales of the Wayside Inn, where a group of fictitious European colonialists meet for some storytelling at what is now a famous inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts. As fate would have it, my maternal grandparents happened to live right down the road from the Wayside Inn in Marlborough and as a child they would take me and my siblings to play in the nearby woods and explore the nearby grist mill where I would search for dinosaurs and dragons with my twin brother and younger sister. So, you can imagine, I’ve had my share of meals and heard my own share of tales at the Wayside Inn—in fact my father’s second marriage held its reception there—so the place has special meaning to me, a sort of gravitas. Having grown up a few towns over in Massachusetts, I always found the inn and surrounding area charming, but the historical and literary influence of the space in which I have lived most my life continues to find new ways of inspiring me, especially as I have recently returned to work and teach in Marlborough and have begun to reconnect once again with the area. This brought my mind back to Longfellow’s tales.

Longfellow writing on the eve of the American Civil War is none other than the author credited with reimagining the story of Paul Revere’s midnight ride, in his “The Landlord’s Tale” also known as “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” in which American revolutionary figure, Paul Revere, is the dashing hero who delivers the all-important message, undercutting Samuel Prescott’s successful journey out of the story entirely, and erasing Revere’s capture and partial failure by replacing it with a version of events in which Revere is victorious in his epic quest.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

(Longfellow, “The Landlord’s Tale: The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” 199-130).

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,—

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere!

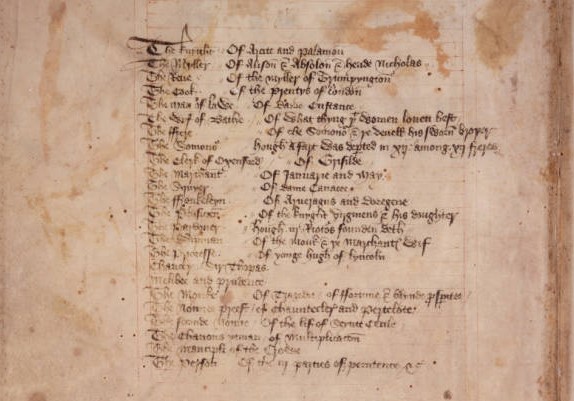

Other tales told by European colonials at the Wayside include: “The Student’s Tale” “The Spanish Jew’s Tale” “The Sicilian’s Tale” “The Musician’s Tale” “The Theologian’s Tale” and “The Poet’s Tale”. These titles chime with Chaucer’s titles named for each distinct pilgrim on the road to Canterbury, some of which include “The Knight’s Tale,” “The Miller’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale,” and “The Pardoner’s Tale.”

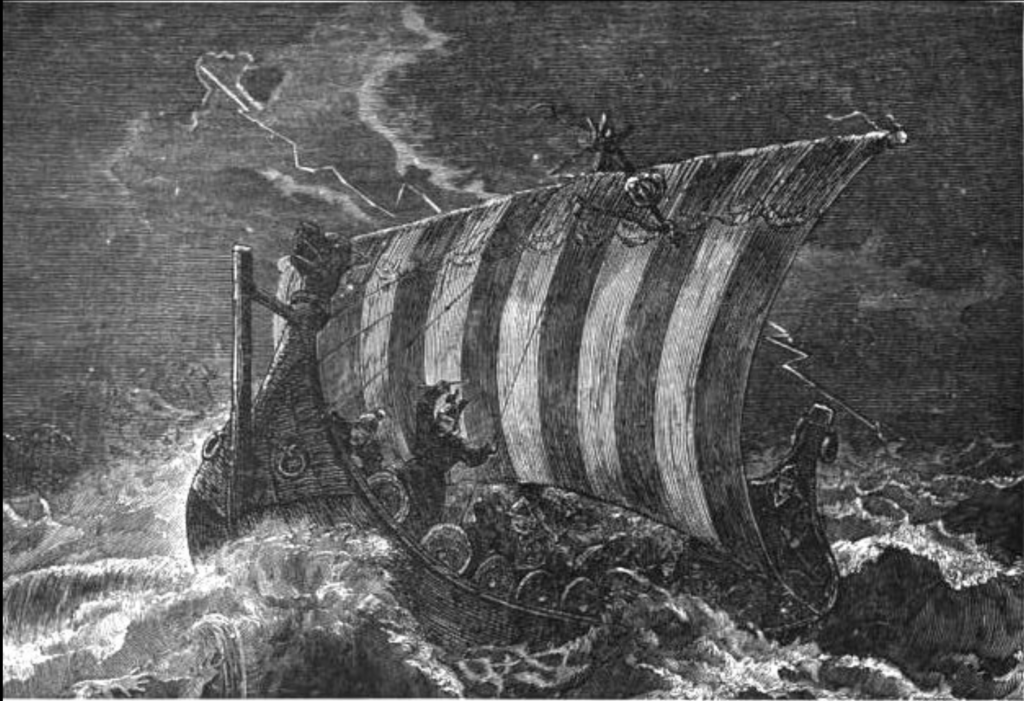

My blog today will end with a brief introduction to Longfellow’s “The Musician’s Tales” which is also called “The Saga of King Olaf” in reference to Old Norse-Icelandic Saga Olafs konungs Tryggvasunar. Structurally, the tale is the longest tale—a sort of epic poem—with subtitled chapters.

i. The Challenge of Thor

ii. King Olaf’s Return

iii. Thora of Rimol

iv. Queen Sigrid the Haughty

v. The Skerry of Shrieks

vi. The Wraith of Odin

vii. Iron-Beard

viii. Gudrun

ix. Thangbrand the Priest

x. Raud the Strong

xi. Bishop Sigurd at Salten Fiord

xii. King Olaf’s Christmas

xiii. The Building of the Long Serpent

xiv. The Crew of the Long Serpent

xv. A Little Bird in the Air

xvi. Queen Thyri and the Angelica Stalks

xvii. King Svend of the Forked Beard

xviii. King Olaf and Earl Sigvald

xix. King Olaf’s War-Horns

xx. Einar Tamberskelver

This heavily alludes to Old Norse-Icelandic Heimskringla which Longfellow had access to via Samuel Laings’ modern English translation published in 1844. In doing so, this tale draws directly from Old-Norse Icelandic saga literature and serves to connect early American literature and mythography with early medieval Europe and antiquarian notions of “The Germanic” and “Anglo-Saxon” ethnonationalist identities. The first poem, “The Challenge of Thor” demonstrates how Viking warrior ethics and mythology are interwoven directly into early American literature and mythography. The challenge reads almost as an invocation to the pagan god of Northern medieval Europe in a romantic display of American eurocentrism:

I am the God Thor,

(Longfellow, “The Musician’s Tale: The Challenge of Thor” 1-42).

I am the War God,

I am the Thunderer!

Here in my Northland,

My fastness and fortress,

Reign I forever!

Here amid icebergs

Rule I the nations;

This is my hammer,

Miölner the mighty;

Giants and sorcerers

Cannot withstand it!

These are the gauntlets

Wherewith I wield it,

And hurl it afar off;

This is my girdle;

Whenever I brace it,

Strength is redoubled!

The light thou beholdest

Stream through the heavens,

In flashes of crimson,

Is but my red beard

Blown by the night-wind,

Affrighting the nations!

Jove is my brother;

Mine eyes are the lightning;

The wheels of my chariot

Roll in the thunder,

The blows of my hammer

Ring in the earthquake!

Force rules the world still,

Has ruled it, shall rule it;

Meekness is weakness,

Strength is triumphant,

Over the whole earth

Still is it Thor’s-Day!

Thou art a God too,

O Galilean!

And thus single-handed

Unto the combat,

Gauntlet or Gospel,

Here I defy thee!

The references to hazardous weather and natural disasters, such as earthquakes, lightning and thunder, and allusions to Mjölnir (10) and Thor’s girdle (16), are enveloped in the themes of “Force rules the world still” (31) and “Meekness is weakness” (33) in the poem. Additional references to Thor’s “red beard” (22), his goat-drawn “chariot” (27) and his syncretism with Thor and Zeus is dramatized in the line “Jove is my brother” (25). As Irving does with Wednesday as “Wodensday” (2) in “Rip Van Winkle,” Longfellow too emphasizes how Thursday derives from “Thor’s-Day” (36) and thus highlights the pervasive cultural resonance rooted in the medieval lore sung by the musician in their tale. The challenge ends with a direct conflict between Thor and Christ, the “Galilean” (38). Thor names Christ a “God too” (37) but stresses his own continued cultural influence which Thor frames as an affront to Christianity, juxtaposing “Gauntlet or Gospel” (42) and adamantly opposing Christian virtues by challenging Christ’s ethical superiority. This rhetorical move reminds the reader, and perhaps also many early Americans living in the antebellum United States, that United States’ cultural inheritance was repeatedly upheld as distinctly European, and that eurocentric ethnonationalism would remain a shared legacy in both the “old” and “new” worlds thereby helping to erase and ignore indigenous and non-white perspectives.

Further discussion of Henry Longfellow’s medievalism in “The Saga of King Olaf” centered on some of the subsequent sections will be featured in a blog later this spring, so check back soon!

Richard Fahey, Ph.D.

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited:

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. McClelland and Stewart Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1985.

Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron, trans. by John Payne. The Villon Society, London, 1886.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Harvard University, 2023.

Heimskringla, ed. by Finnur Jónsson. Copenhagen, 1911.

Helgisaga Óláfs konungs Haraldssonar, ed. Guðni Jónsson. Reykjavík, 1957.

Irving, Washington. “Rip Van Winkle” in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., 1819.

—. “Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., 1819.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Tales of the Wayside Inn. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1863.

Further Reading:

Calin, William. “What Tales of a Wayside Inn Tells Us about Longfellow and about Chaucer” in Studies in Medievalism XII – Film and Fiction: Reviewing the Middle Ages, ed. by Tom Shippey and Martin Arnold, 197-214. Boydell & Brewer; D. S. Brewer, 2003.

Lowrie, Robyn. “My American Poetry Review of Henry W. Longfellow’s ‘The Belfry of Bruges.'” My French Quest: Adventures in Literature, French Culture and Language Acquisition, 2016.

O’Donnell, Kerry. “The Handmaid’s Canterbury Knight’s Tale.” Utopian, Dystopian, Fantasy Fiction, 2016.

Sheko, Tania. “What’s in a Tale? The Canterbury Tales and The Handmaid’s Tale.” Red or Dead, 2017.

Trzcinski, Matthew.“The Handmaid’s Tale Author Changed the Original Name of the Book.” Showbiz Cheat Sheet, 2021.