In June of 2023, I arranged to meet my friend and fellow historian Caoimhe Whelan for a short breakfast during one of my rare trips to Ireland. I had given the rest of the day over to research, a concession of one day in what was supposed to be a family holiday. At breakfast, Caoimhe introduced me to Stuart Kinsella, Christ Church Cathedral’s Research Advisor; he was chasing down the scribes and notaries of the Cathedral’s later medieval manuscripts, and had run across a few pages at the back of my dissertation – an appendix cataloguing all of the notaries I had found in the process of investigating the life and career of Anglo-Irish author and notary James Yonge. In introducing me to Stuart, Caoimhe inadvertently cancelled my vacation. Breakfast was consumed. We talked. We ordered coffee. Stuart got out his carefully compiled list of notaries. We talked some more. Soon we were ordering lunch. We compared images, debated the merits of early 20th-century drawings of documents lost in a catastrophic 1922 fire a half mile from where we sat, and began making plans. By the end of the morning, we had explored several possibilities for a project far wider than my study of James Yonge or Stuart’s study of Christ Church scribes and notaries. Every spare moment I could get for the rest of my time in Ireland was given over to notaries. (Caoimhe would go on to destroy my summer holidays the following year with a grainy image of a notarial signum taken at Sarah Graham’s lecture at Leeds, but that is a tale for another time.)

Notaries were specialized legal scribes used principally by the ecclesiastical courts to record proceedings and produce official documents. Notaries could be found in every corner of medieval and early modern Europe, and were particularly prevalent on the Italian and Iberian peninsulas where they also played a role in civil courts. In England and English-controlled Ireland, English civil law did not provide for notaries, and as a result they were far fewer in number. Notaries found their way, however, into civil procedures, particularly in cases where an official witness was needed. Notaries not associated with the church were paid by laypeople to produce documents that might be helpful in future cases in the ecclesiastical courts, particularly those regarding marriage or legitimacy.[1] In Anglo-Ireland, these specialized scribes also created new, authenticated copies of documents that had become faded or damaged. Notaries also served as official witnesses in disputes, creating documents functioning similarly to a sworn deposition; their instruments record in a matter-of-fact way dramatic moments in the lives of ordinary people. For instance, a 1406 instrument of James Yonge records that Robert Burnell wanted John Lytill to place his seal on some documents; Lytill refused, and Burnell responded by seizing Lytill in a Dublin street and holding him hostage until he acquiesced.[2] Another instrument by Thomas Baghill records an attempt to interfere in a will. On his deathbed, William Moenes was approached by his brother, Robert, who attempted to claim William’s property, despite the objections of William himself, who even in his extremity protested that he wished his property to go to his uncle’s daughters.[3] Both of these instruments were probably intended for later use in civil cases regarding the disposition of property.

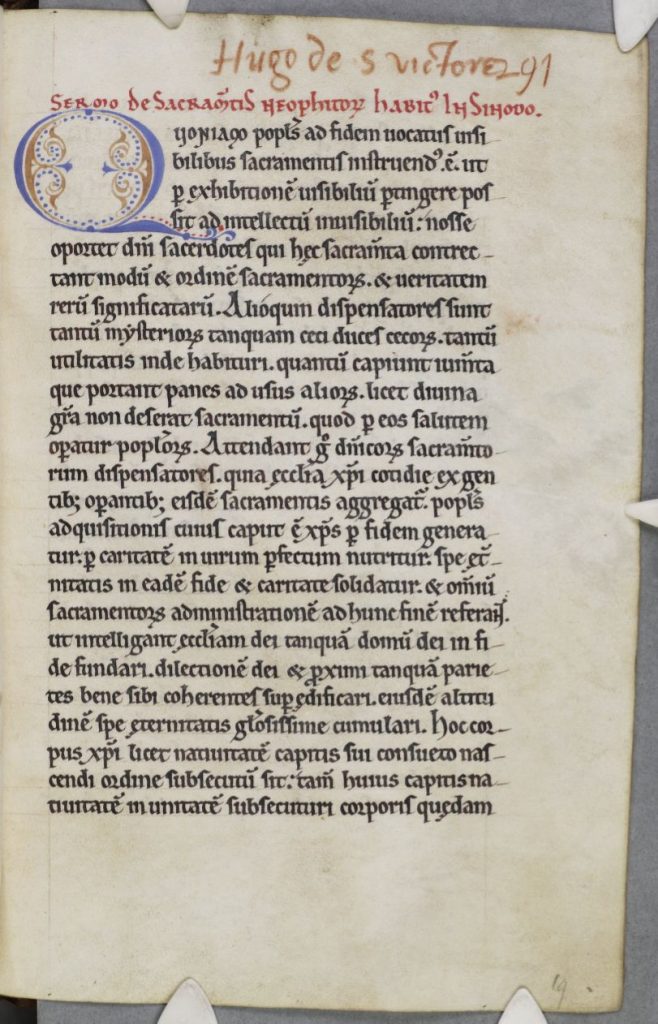

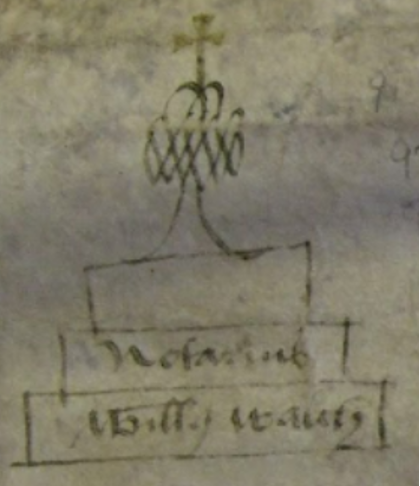

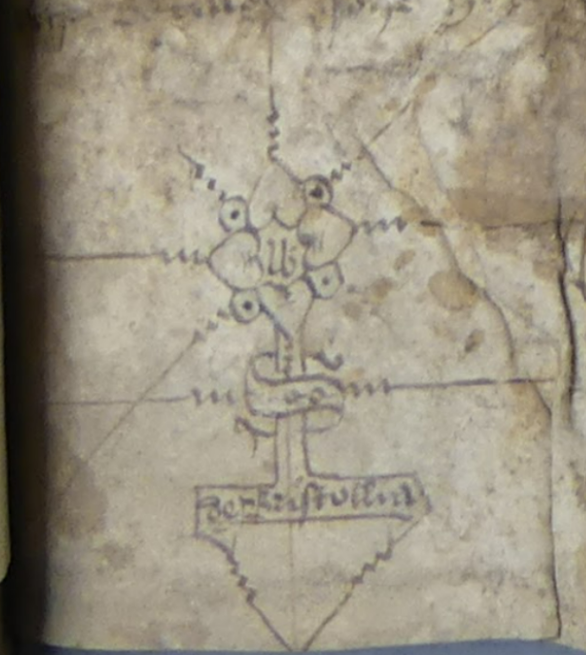

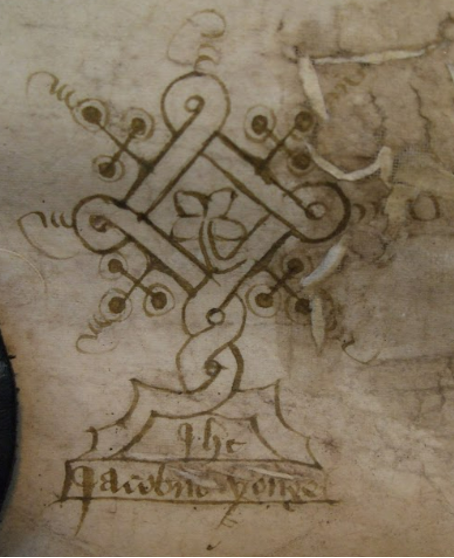

Notarial instruments are most easily identified by their signa. Each notary developed his own unique signum manuale, a pen-and-ink drawing that he used to authenticate the documents he created. These frequently looked like altar crosses. During the Tudor period, notarial signa became panels of knotwork.

Once developed, a notary’s signum remained fixed; he would use the same signum for the rest of his career. On an instrument, the signum manuale is also accompanied by an eschatocol, a formulaic attestation that the notary has heard and witnessed what is recorded in the document and that the contents are true to the best of the notary’s knowledge. Eschatocols frequently begin with an E that can be quite plain or highly ornamented, depending on the notary. Again, notaries’ Es tended to remain somewhat fixed. The signum and eschatocol provide a key to identifying a notary’s handwriting in other contexts. For instance, James Yonge was also the scribe of over one hundred surviving documents, signed and unsigned. Notary William Somerwell, who worked for the archbishops of Armagh, was also one of the principal contributors to the registers of archbishops Nicholas Fleming (1404-1416), John Swayne (1418-1439), John Prene (1449-1453), and John Mey (1443-1456).

Signa have also been instrumental in identifying groups of notaries. For instance, James Yonge’s student Thomas Baghill borrowed portions of his master’s signum when developing his own.[4]

We’ve also discovered signa in contexts outside of notarial instruments. Of particular note is the signum of an as-yet-unidentified notary in the margins of a Hiberno English translation of Gerald of Wales’ Expugnatio Hibernica.[5]

Our survey of Anglo-Irish notaries is still in its infancy, and we are seeking sources of funding. We are currently trying to document as many notaries from medieval and early modern Ireland as possible as an entry into a larger exploration of notaries’ training, scribal networks, and documents. We hope to create a searchable online database of notarial marks and scribal hands for Ireland as a starting point for a more extensive resource cataloging the marks of medieval and early modern notaries of the British Isles. We would also love to see a future collaborative database of European notaries.

Ian Doyle once wrote of palaeography that “the jigsaw puzzle we are all working on is so big that it may need the help of every eye to try to fit a piece in it.”[6] We believe the same is true of medieval and early modern notaries. This is where you, dear reader, come in. We heartily invite researchers in any area of medieval and early modern Europe to let us know about any notaries or notarial signa you encounter in your own research. The project’s email address is notarius.ie@gmail.com. We welcome your comments and contributions!

Theresa O’Byrne

Associate Researcher, Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland

Latin and history instructor, Delbarton School

[1] C.R. Cheney, Notaries Public in England in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, p. 56; Patrick Zutshi, “Notaries Public in England in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries,” Historia, Instituciones, Documentos 23 (1996), pp. 421-33, at p. 426.

[2] Trinity College Dublin MS 1477, no. 69, 16 March 1406.

[3] Royal Irish Academy 12.S.22-31, no. 826, 17 April 1434.

[4] Theresa O’Byrne, “Notarial Signs and Scribal Training in the Fifteenth Century: The Case of James Yonge and Thomas Baghill,” Journal of the Early Book Society 15 (2012): 305–18.

[5] Trinity College Dublin MS 592, fol. 6v.

[6] A.I. Doyle, ‘Retrospect and Prospect’, in Manuscripts and Readers in Fifteenth-Century England, ed. D. Pearsall (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 142–6 (pp. 145–6).