What did early mathematical education look like in the Middle Ages? As is commonly known, the ideal Liberal Arts curriculum of the Middle Ages featured both the Trivium (dedicated to the study of words) and Quadrivium (dedicated to the study of nature in the form of mathematical arts). The Trivium included Grammar, Logic, and Rhetoric. The Quadrivium consisted of Music, Astronomy, Geometry, and Arithmetic. These seven ways (viae) of liberal arts learning prepared students who studied them diligently to “comprehend everything that they read, elevat[ing] their understanding to all things and empower[ing] them to cut through the knots of all problems possible of solution” (John of Salisbury, Metalogicon I.12). Even today, the concept of a Liberal Arts education that prepares a student for life and whatever (foreseen and unforeseen) challenges lay aheadremains. And yet, for anyone who has educated a child, the idea of delaying mathematical education until the early teen years (which is when the formal Quadrivium was taught) seems completely impractical and misguided.

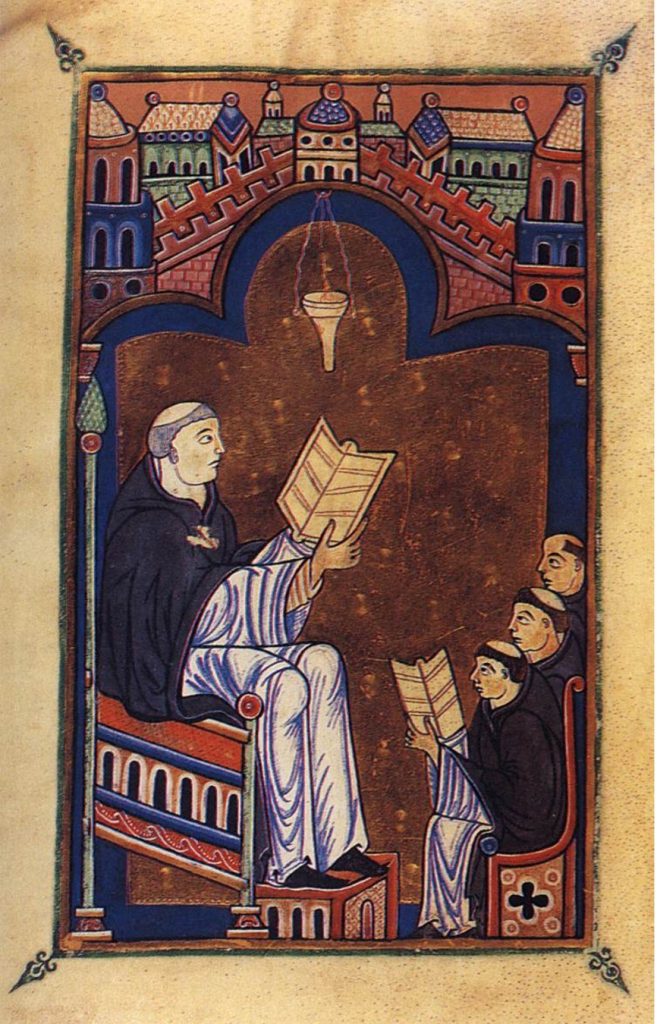

Did medieval educators really wait until students had a full understanding of the Trivium before introducing mathematics? The difficulty here comes in part from the lack of extensive knowledge of the curriculum of early childhood medieval education, including mathematical instruction. The institutions for learning changed over time and even geographic region. Early childhood education could take place in a home, in a monastery, or at a local cathedral school. Another difficulty may also be that our cultures mean slightly different things when we talk about the discipline of mathematics.

The “paper trail” for exactly what early childhood mathematical education might have looked like is not vast. But one tiny, but vivid, glimpse of what boyhood mathematical pursuits might have looked like can be seen in the writings of Hugh of St. Victor, an early twelfth century canon regular who wrote a book on the Liberal Arts called the Didascalicon. In this work, Hugh of St. Victor gives a rare view of his own early mathematical education:

I laid out pebbles for numbers, and I marked the pavement with black coals and by a model placed right before my eyes, I plainly showed what difference there is between an obtuse-angled, and an acute triangle. Whether or not an equilateral parallelogram would yield the same area as a square when two of its sides were multiplied together, I learned by walking both figures and measuring them with my feet. Often I kept watch outdoors through the winter nights like one of the fixed stars by which we measure time. Often I used to bring out my strings, stretched to their number on the wooden frame, both that I might note wih my ear the difference among the tones and that I might at the same time delight my soul with the sweetness of the sound. These were boyish pursuits…yet not without their utility for me, nor does my present knowledge of them lie heavy upon my stomach. (VI.3)

Hugh describes these activities as grounding him “in things small” so that he could “safely strive for all” later in life.

Notice how many of the activities mentioned by Hugh of St. Victor do not require a textbook at all, especially with a charismatic teacher, or in the case of Hugh’s own life, a particularly inquisitive child. Counting and the study of angles required only pebbles. The figuring of surface area required only the measurement of feet. An early acquaintance with the stars required actually going out to look at the night sky, even when it was cold, and the study of the relationship between musical notes came from literally fiddling around with a simple stringed instrument. To these activities, we might presumably add the common medieval practices of singing (cantus) and possibly dancing in set patterns. Or the calculating of times and seasons (computus). Or measurements of land and sea masses for commerce or geography. Or ratios for cooking. Many of these activities can be conveyed orally through constant interaction with numbers in the physical world. That is not to say that no formal study or book learning could or was be done in these areas, but the bulk of early mathematical learning did not need to take place in a school environment with a textbook. All that was needed was a student, the physical world, and a teacher with mathematical knowledge.

What Hugh recognized was that these mathematical activities, whether for play or practical application, were essential for what he and his contemporaries would have considered the formal discipline of mathematics as a liberal art (i.e. the Quadrivium), which would have taken place during the teenage years at higher level schools. Hugh distinguishes arts and disciplines in the following manner: “Knowledge can be called an art ‘when it comprises the rules and precepts of an art’ as it does in the study of how to write; knowledge can be called a discipline when it is said to be ‘full’ as it is in the ‘instructional’ science, or mathematics” (II.1).

In other words, the sorts of activities Hugh describes himself doing as a boy were not mathematical disciplines in his terminology. Instead, his boyish mathematical play was both pleasant at the time and useful as he grew up to study the mathematical disciplines. For this reason, Hugh praised such activity as best because it aids one’s movement “step by step” rather than “fall[ing] head over heels when [attempting] to make a great leap ahead” (VI.2). This learning process mirrors the original discovery of the disciplines themselves by humanity. As Hugh writes:

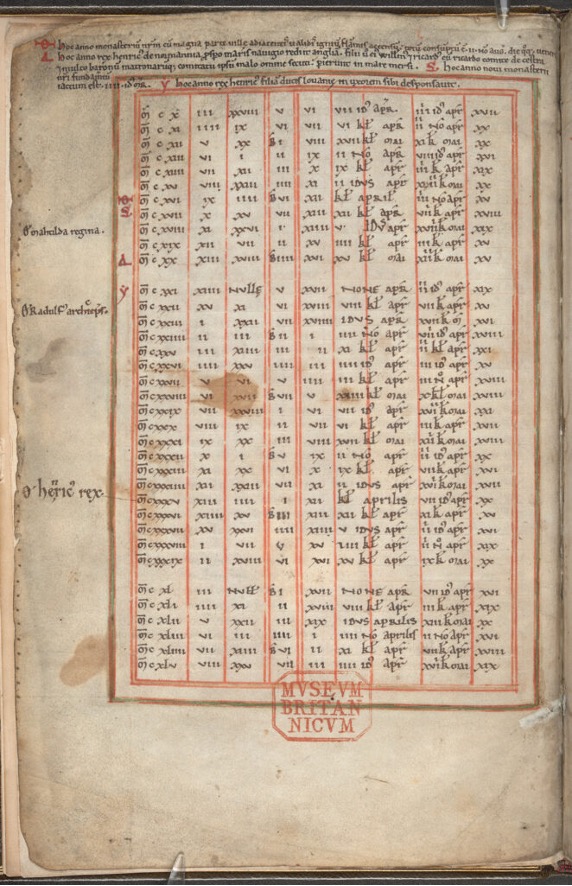

Such was the origin of all the arts; scanning them all, we find this true. Before there was grammar, men both wrote and spoke; before there was dialectic, they distinguished the true from the false by reasoning; before there was rhetoric, they discoursed upon civil laws; before there was arithmetic, there was knowledge of counting; before there was an art of music, they sang; before there was geometry, they measured fields; before there was astronomy, they marked off periods of time from the courses of the stars. But then came the arts, which, though they took their rise in usage, nonetheless excel it. (I.11)

Early childish mathematical play was not the Quadrivium, but Hugh considered it a necessary preparation for the later study of the Quadrivial arts. Just as Boethius argued in Institutio arithmetica 1,1,7 that the quadrivium provides steps (gradus) by which the mind is progressively illuminated and can raise itself from its immediate sensible circumstances to the certainty of intelligible truth, so Hugh argued that the humble mathematical play of childhood was one step on the way to learning the discipline of mathematics. Computus, stargazing, learning to sing, learning to dance, and making geometric shapes with pebbles—none of this was Quadrivium. These activities could be boyhood pursuits…or in some cases, ends in themselves practiced into adulthood, but activities of this sort were, in Hugh’s opinion, a necessary preparatory step for the Quadrivial disciplines.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams is a Professor for Memoria College’s Masters of Arts in Great Books program and graduated with her doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute in 2012. She was also the founding director Liberal Arts Guild at LeTourneau University. Her research focuses upon twelfth-century Platonism and poetry, especially Thierry of Chartres and Bernard Silvestris.

Further Reading:

Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts. Edited & translated by Jerome Taylor, Columbia University Press, 1991.

Jaeger, C. Stephen. The Envy of Angels: Cathedral Schools and Social Ideals in Medieval Europe, 950-1200. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994.

John of Salisbury. Metalogicon. Translated by C.C.J. Webb, Clarendon Press, 1929.

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children. Yale University Press, 2001.

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Schools. Yale University Press, 2006.