In an earlier blog post, I wrote about four fables where animals “dress up” as another species, and looked at these in terms of socioeconomic class—this is what medieval authors like Marie de France, Robert Henryson, and Alexander Neckam were clearly aiming to comment on, and these fables can be seen, I argued, in the context of medieval sumptuary laws and anxiety about social mobility.

I’d now like to revisit the same fables, considering them this time through a different lens: trans experience. This way of interpreting these fables has been on my mind the whole time. In discussing the fables with other people, I have found that they readily come up with trans readings of them (i.e., they suggest to me that the stories about one species wearing the skin or feathers of another can be seen as metaphors for being transgender, and that a trans reading of them could be interesting). As someone who hasn’t really worked in trans studies before, I have felt underequipped, in terms of offering a theoretically-informed take that meaningfully incorporates other scholarship in this area (there is a lot of exciting new work being done in trans medieval studies; see “Further Reading,” below, for a very non-comprehensive selection).

Despite this hesitation on my part, a trans reading of these fables feels far more salient to me right now than a socioeconomic one, and I think there are more urgent ethical stakes; medieval sumptuary laws are obsolete (and were, at the time, apparently rather ineffectual), whereas trans people are currently a hypervisible minority whose rights are under attack.

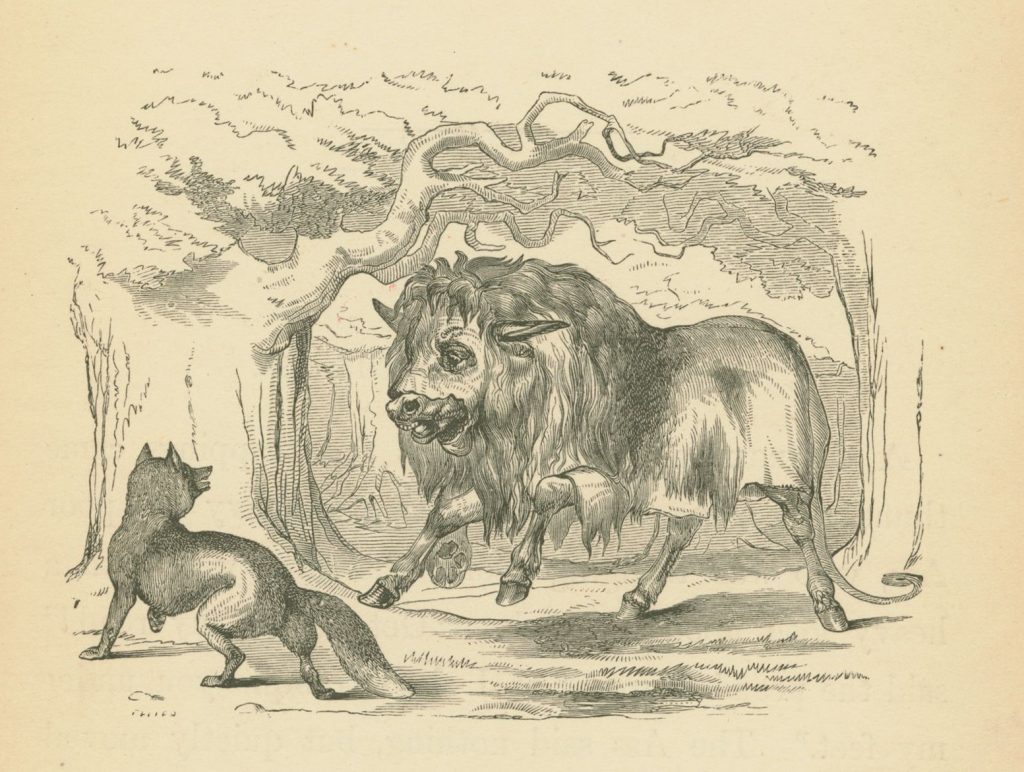

The thing is, when you look at these fables as trans narratives, they send a bleak message. These fables essentially suggest, as many other fables do as well, that we can never escape certain fundamental, supposedly “natural” categories, and that trying is dangerous and inadvisable. I’d like to look more closely at a couple of versions of a single fable, The Ass and the Lion Skin (Perry Index 188/358), to illustrate how this message is set up, as well as the parallels one could see between what befalls these fictional animal characters and the experiences of trans humans.

The first version I discuss is a Latin prose fable from the thirteenth century, by Odo of Cheriton:

Asini uiderunt quod homines male et dure tractauerunt eos, stimulando, (h)onera imponendo. Viderunt etiam quod timuerunt Leones. Condixerunt ad inuicem quod acciperent pelles leoninas, et sic homines timerent illos. Fecerunt sic. Asini igitur, induti pellibus leoninis, saltabant, discurrebant. Homines fugerunt credentes esse Leones. Tandem Asini inceperunt recanare. Homines diligenter auscultauerunt et dixerunt: Vox ista uox Asinorum est; accedamus proprius. Accesserunt tandem; viderunt caudas illorum et pedes et dixerunt: Certe isti sunt Asini, non Leones, et ceperunt Asinos et multum bene uerberauerunt.1

The donkeys saw that humans treated them badly and harshly, striking them and putting burdens on them. They also saw that they [i.e., the humans] were afraid of lions. They decided amongst themselves to put on lion skins, and that way humans would be afraid of them. They did this. And so the donkeys, wearing lion skins, leapt and ran about. Humans fled, thinking that they were lions. Eventually the donkeys started braying. The humans listened carefully and said: “That sound is the sound of donkeys; let’s get closer.” After a while they got up close; they saw their tails and feet and said, “Clearly these are donkeys, not lions,” and they seized the donkeys and beat them very thoroughly.

Odo’s moral then proceeds to analogize the wayward donkeys to “false men” (homines falsi), particularly those in the Benedictine order; his fables often criticized the clergy.

Odo’s version of this fable differs from others in some respects, e.g., the earliest version, which is also in Latin (Avianus, ca. 400 CE),2 or the late Middle English version in Caxton’s Aesop.3 While in the latter two versions, a single donkey comes across a lion skin by chance, in Odo’s telling, the act of donning lion skins is a collective decision by multiple donkeys, a calculated response to their ill treatment by humans. These donkeys aren’t just taking on the appearance of a different species, they are taking on the appearance of a much higher-status species, in an attempt to protect themselves (lions often stand in for tyrants, rulers, kings, etc. in fables, whereas fable donkeys are typically quite abject). If we are reading species as analogous to gender, here, there are, of course, differences of power and privilege when it comes to gender, too. The fact that women and men are not simply treated differently, but unequally, has induced some feminists to assert that transmasculine identities arise as a response to the social pressures of misogyny (i.e., that transmasc people are trying to “escape” womanhood because being a woman in a patriarchal culture is painful). One troubling implication of this line of thought is that a lot of trans people simply wouldn’t exist as such, in an “ideal” society without gender inequality.

In The Ass and the Lion Skin, the wearing of a new skin is not just a matter of appearance; the animal in the lion skin looks different, and they behave differently as well, chasing others as though they were a feline predator instead of an equid beast of burden. Initially, those other characters react to the donkey(s) as if they were indeed a lion, until something gives the donkey away. If we choose to read Odo’s fable through a trans lens (though his aim seems to have been to denounce clerical misbehavior), the fact that it is the donkeys’ brays that give them away might sound familiar to anyone who has dysphoria about their voice not matching their gender identity, and anyone who has been misgendered after starting to speak.

The humans in this fable scrutinize, too, specific physical characteristics—the tail and feet—and on those grounds determine what the donkeys “really” are, and react with violence. I can’t help but think of “transvestigators” who pore over photos of trans people (or cis people that they think might be trans), insisting that a particular feature reveals that the photo’s subject is quintessentially male or female, at odds with their presentation and identity. I also can’t help but think that being “clocked” as trans can indeed be the prelude to experiencing hostility, from hate speech to physical violence.

Not only do the donkeys undergo physical violence, this violence is intended to restore the status quo. It is coupled with a kind of ontological violence—the (re)definition of the target in the dominant party’s terms. “Clearly, these are donkeys, not lions,” the men say before beating them. Even more strikingly, in Avianus’s version, the donkey’s master concludes by saying, “Maybe you can trick strangers with your imitation roar; to me, you will always be a donkey, as you were before” (forsitan ignotos imitato murmure fallas; at mihi, qui quondam, semper asellus eris, lines 17–18). In a trans context, this makes me think of a stubborn family member who insists that they simply can’t perceive or treat their relative as their actual gender identity, because they’ve spent so many years thinking of them as the gender assigned to them at birth.

So, when I look at these “trans-species” fables in terms of transgender experience, my takeaway is depressing. The texts promote a status quo in which no one really can, or should try to, appear or behave outside of the categories “nature” has assigned. They gloss the act of wearing a “new skin” as a form of untenable inauthenticity, and portray the “trans-species” characters as being inevitably put back in their place with violence. These are the lessons we are seemingly meant to learn.

I want to do some kind of reparative reading of these fables, and to find something liberatory or subversive, but I struggle to, because the texts themselves do work in the opposite direction—and transphobes have recognized that. Another famous fable of an animal wearing a different skin—the fable of The Wolf that Dressed in a Sheepskin (Perry Index 451), in which a wolf mimics a sheep in order to better prey on the flock—has been used in recent years by anti-trans authors and cartoonists (who I won’t platform with links—this should be easy to find if you wish). This kind of rhetoric often fixates on transfemininity, in particular, portraying trans women as deceptive and even dangerous. For instance, the trope of predatory men-dressed-as-women attempting to infiltrate women’s bathrooms has been used as an argument for anti-trans “bathroom bans,” which have been passed in 19 US states over the last four years, part of a larger wave of anti-transgender legislation. The “bathroom ban” laws purport to address what is in fact a thoroughly imaginary problem, making bathrooms less safe for anyone who is trans and/or gender non-conforming.

What do we do with didactic literature, stories that aim to teach lessons—in this case, medieval fables with morals—if the lessons are not ones we want to endorse or to heed, and if the stories themselves are being weaponized against a vulnerable minority? I don’t know. I think one step is to acknowledge that these texts are “naturalizing” social categories by mapping them onto different animal species, in order to suggest that social differences (such as class and gender) are starkly distinct and immutable, impossible to change—as impossible as it would be for a donkey to become a lion, or a wolf to become a sheep. However, as I argued in the previous post, if these social categories actually were “natural,” “biologically innate,” and unalterable, there would be no impetus to tell stories, over and over again, warning people not to act “unnaturally.”

Nonetheless, if we want liberatory or subversive trans fables, we might have to write them, or rewrite them, rather than looking to the medieval versions of these particular texts.

Linnet Heald

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading:

- Bychowski, M.W. “Trans textuality: Dysphoria in the depths of medieval skin.” postmedieval 9.3 (September 2018): 318–333.

- Gazzoli, Laura. “Medieval Literature as Trans Literature.” The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Douglas A. Vakoch and Sabine Sharp. Routledge, 2024.

- Kim, Dorothy, and M. W. Bychowski. “Visions of Medieval Trans Feminism: An Introduction.” Medieval Feminist Forum, vol. 55, no. 1 (2019): 6–41.

- Klosowska, Anna, Masha Raskolnikov, and Greta LaFleur, eds. Trans Historical: Gender Plurality Before the Modern. Cornell University Press, 2021.

- Malcolm, Aylin and Nat Rivkin. “Introduction: Medieval Trans Natures,” Medieval Ecocriticisms, Vol. 4, Article 2 (2024)

- Wingard, Tess. “The Trans Middle Ages: Incorporating Transgender and Intersex Studies into the History of Medieval Sexuality,” The English Historical Review, 2024.

- Latin text from Léopold Hervieux, Les Fabulistes latins depuis le siècle d’Auguste jusqu’à la fin du moyen âge, vol. 4, Eudes de Cheriton et ses dérivés (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1896), pp. 198–99. All translations in this post are mine. ↩︎

- Duff, Arnold Mackay, and John Wight Duff, eds. Minor Latin Poets, Volume 2. Loeb Classical Library, vol. 434. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2006, p. 690. ↩︎

- Lenaghan, R. T., ed. Caxton’s Aesop: Edited with an Introduction and Notes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967, p. 179. ↩︎