Saint Catherine of Alexandria was hugely popular in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Europe. Her legend was copied and adapted more frequently in Middle English than any other saint’s.1 One reason for this was her appeal to a growing literate-female audience; as martyrs go, St. Catherine was a pretty awesome role model:

- She was extremely well-educated (sometimes identified as a princess)

- She dominated all the men in public rhetoric battles

- She survived a Wheel of Torture (which in turn shattered and killed everyone else)

- And she played impossible-to-get with the enamored (evil) emperor (until he finally gave up on love and killed her).

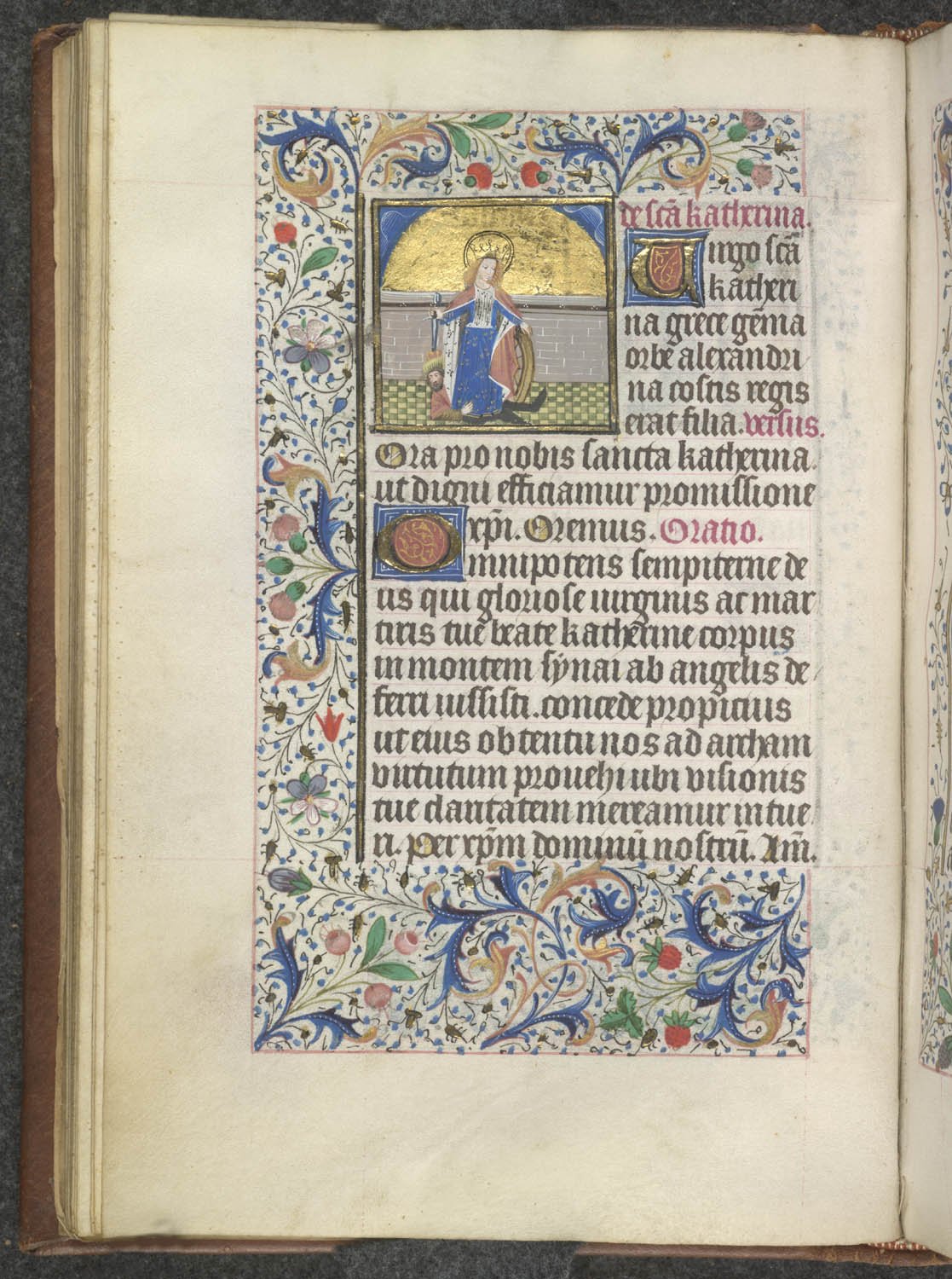

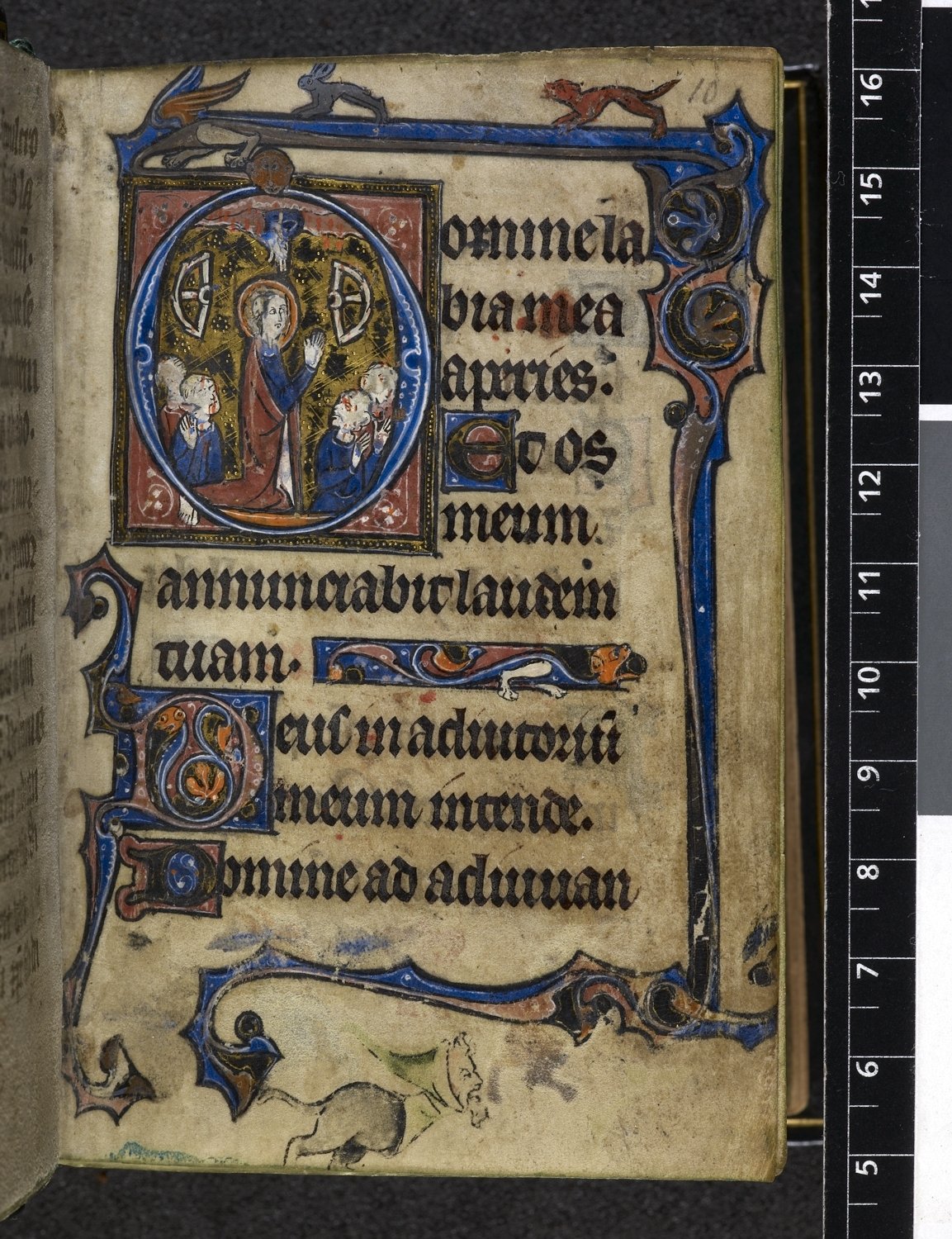

The images above are all from Books of Hours, a genre of devotional texts often commissioned by and for the use of noble women. As such, the pictures—as much as the text—inform the reader’s meditation on her character; we can “read” the particular legend of Catherine portrayed by each artist.

In the first illustration, we have St. Catherine (we know because of the broken torture wheel, which here looks entirely unthreatening) reading calmly in a garden near the port of Alexandria—or, alternatively, one’s local English port.

She wears the clothes of a noblewoman—maybe similar to what our 15th-century reader would wear. And, as the patron saint of learning scholars, Catherine is even reading, like her reader! By putting Catherine in the reader’s shoes, this image in turn helps the reader liken herself to Catherine.

The second illustration has our heroine, sporting her wheel, unapologetically dominating a man (ostensibly the emperor).

Note that this never literally happens in the story, but this image cuts to the point. Of the two figures, Catherine wears the superior crown, her “crown of martyrdom.”2 This image highlights Catherine’s defeat of sin and death, which the licentious and bloodthirsty emperor embodies. The moral of the image seems to be, “You too, women, can conquer with sanctity!”3

The third illustration is an historiated initial: the capital D (which certainly resembles an O) of Domine frames the scene of Catherine’s miraculous defeat of the wheel—broken here by, apparently, her halo and the hand of God.

Though kneeling, Catherine towers over the men around her as in the second image; like the first image, this one emphasizes a resemblance between the reader and the saint: both are presently engaged in prayer.

But what is perhaps more curious, a dragon-creature’s head smiles daftly down over the hand of God, spoiling the vertical hierarchy. Why such irreverence as the critters scattered across Catherine’s page?

It might have to do with the mnemonic function of prayerbook illustrations. The repetition of reading daily prayers would lead to memorization; after a short while, the book would function primarily as a series of visual reminders. That the dragon interacts with the image of Catherine might suggest that the memorable marginalia are not enlisted for their own sakes, but to point to Catherine. Perhaps this dog and rabbit say, “Remember this page; remember Catherine; pray like her!”

Mary Helen Gallucci

PhD Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of an ongoing series on Multimedia Reading Practices and Marginalia: Medieval and Early Modern.