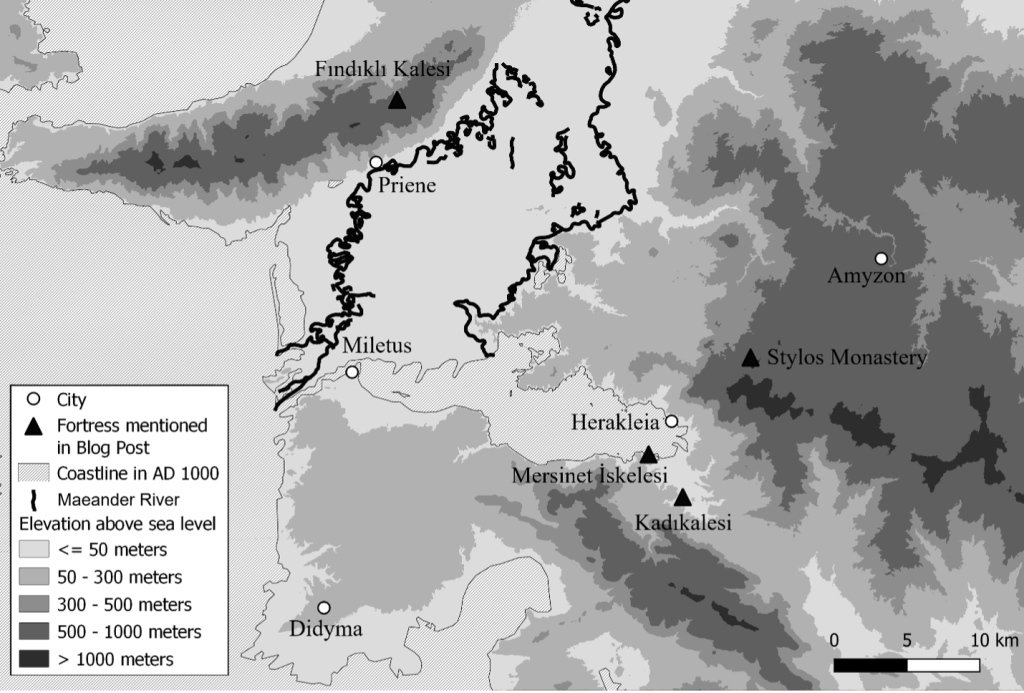

I chose these four fortresses as representations of the observable differences between Byzantine fortified sites. Not all fortifications were made equal. Differences lie not only in the choice of how walls and towers are constructed, but also in the placement of these fortified sites in the landscape. Careful analysis of these features can reveal the underlying assumptions and motivations of the builders. I have chosen among these four fortifications a military base, a refuge, a center for agricultural exploitation, and a fortified residence within the Maeander River valley.

Kadıkalesi[1]

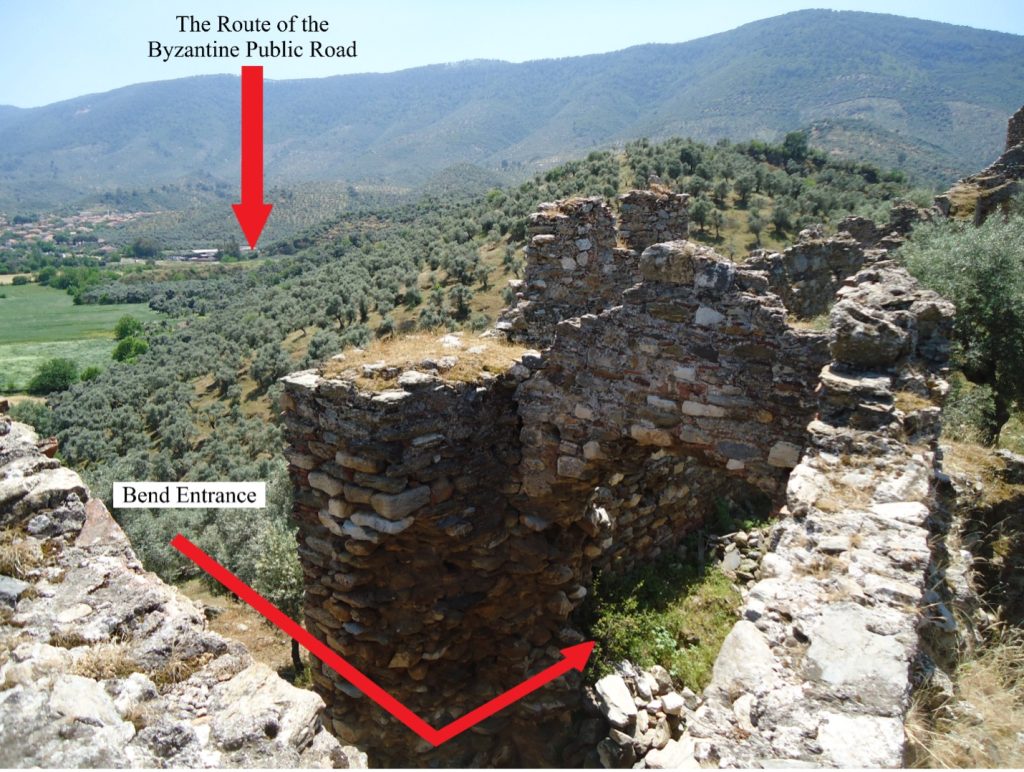

Kadıkalesi is a great example of a military fortress likely built and used by the Byzantine armed forces. The entrances, not just the main one but the two postern entrances too, had a bent gate, which denies an attacker a good view inside the fortress (see Figure 2). The towers project from the walls and include a larger circular tower which is more resilient to projectiles than a square tower. Throughout the entire circuit of walls, platforms known as battlements were built for soldiers to be able to view the landscape. The walls were caped with crenulations, which provided coverage for those soldiers from fire from below (see Figure 3). This fortress was found on a small hill above a road, about 50 meters above sea level. On the one hand, this elevation gave the soldiers good visibility of the surrounding countryside, but, on the other, it was low enough that the soldiers could quickly do something about a threat (see Figure 2).

Fındıklı Kalesi[2]

Fındıklı Kalesi was a large fortress on the top of a mountain, enclosing an area of seven hectares at an elevation higher than 600 meters above sea level. Like Kadıkalesi, the walls were built with military concerns in mind; a series of towers and periodic battlements defend the portions of wall spanning the gaps between rocks, while a double gate fortifies the most vulnerable part of the fortress in the southeast. The size of the fortress was partly determined by geology; the walls follow the edges of a massive rock outcropping. Unlike Kadıkalesi, however, the fortress was isolated from the Byzantine roads that cross the mountain and unable to serve in the policing of routes. I agree with scholars who see Fındıklı Kalesi as a refuge for times of invasion with only a small permanent peacetime population.[3] This was a fortress, not of lords or soldiers, but of farmers and shepherds, who needed its great size to house flocks of sheep and its isolated location to keep just far enough away from any potential raiders that this ‘bluff in stone’ may appear like a formidable military fortress.

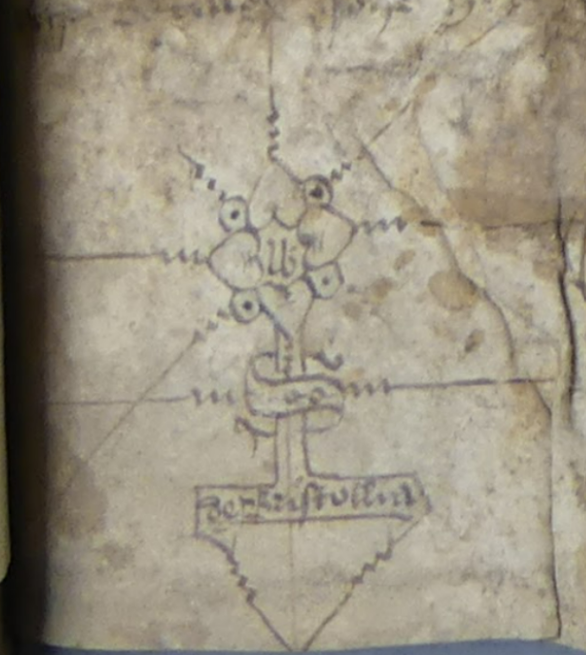

Mersinet İskelesi[4]

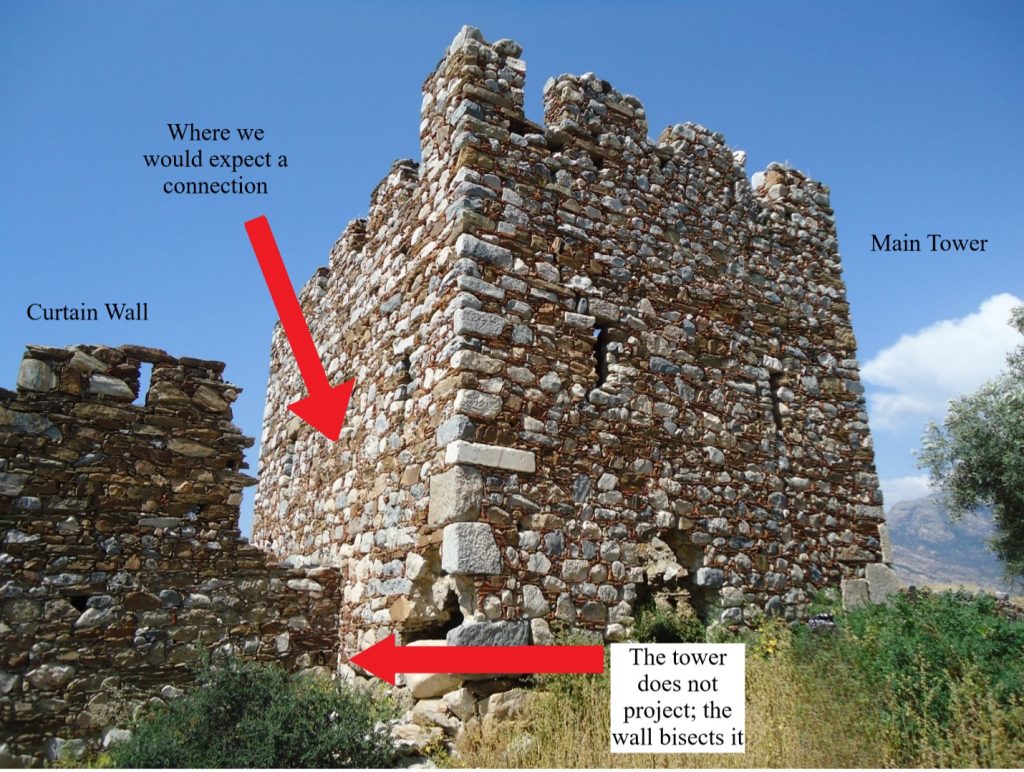

The impressive fortress found on the southern coast of Lake Bafa appears to be a military fort like Kadıkalesi. The use of blind arches to support the battlements even shows an improvement over the thick walls of Kadıkalesi. However, I argue that military effectiveness was not the main concern of this fortress. The defining element of the fortress is a great tower bisected by the enceinte wall. However, there is no communication between the walls and the tower; anyone stationed in the tower could not advance into the battlements in response to a threat. Second, the tower does not protrude from the wall, which decreased its visibility and potential range of fire. While Mersinet İskelesi’s position does provide a good view of the eastern half of Lake Bafa, nearby hills could provide a better view. Instead, this fortress has more in common with the isolated towers found around Lake Bafa and in the wider Maeander Valley. Mersinet İskelesi is an isolated tower with an increased budget. I suspect that this fortress and the other towers have something to do with the exploitation of agricultural estates as these towers lie at the edge of the most plentiful area of farmable land adjacent to Lake Bafa, even if this fortress is usually interpreted as a fortified monastery[5] or military base.[6]

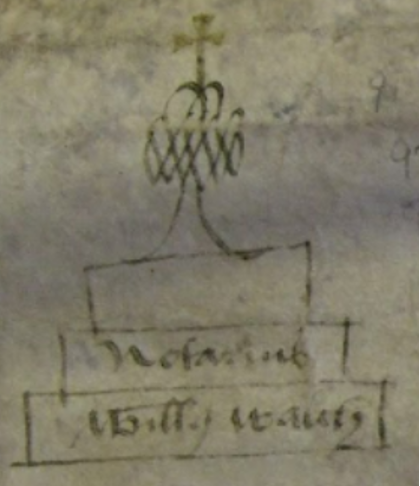

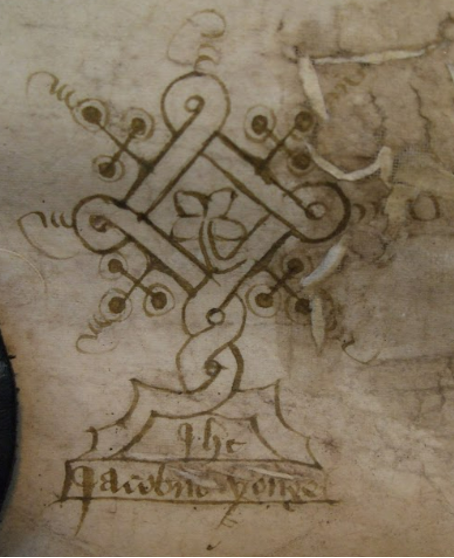

The Monastery of Stylos[7]

The final fortress is the monastery of Stylos. Its walls aided the defense of a community which resided in isolated places like a type of fortified residence. However, this monastery was never intended to operate like a military fortress. For instance, the battlements were limited to walls located at known entrances on the north and south side. They were only interested in watching visitors who intended to use a proper gate and not in observing the wider region. Nor was it a refuge. While the monastery was deep in its mountain like Fındıklı Kalesi, Stylos is near a branch of an ancient road network, which gives the monastery a greater ability to interact with others on and off the mountain. Finally, the division of interior fortification betrays a uniquely monastic concern: the proper veneration of the founder of the monastery. The inner bastion of the monastery contains the hermitage of Saint Paul the Younger cut in a tower of rock and decorated with a painted program of religious images (see Figures 6 and 7). I suspect the fortification of the hermitage likely served to encourage the veneration of their founder and to connect that founder with the builder of the walls, likely Christodoulos of Latros who would go on to found the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian on Patmos. Whatever the purpose of the inner gate was, it is hard to imagine it served the defense of the monastery.

Tyler Wolford, PhD

Byzantine Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

[1] Wolfgang Müller-Wiener, “Mittelalterliche Befestigungen im südlichen Jonien,” IstMitt 11 (1961): 19-23.

[2] Hans Lohmann et al., Survey in der Mykale 1, Bonn: Rudolf Habelt, 2014-2017, II.510-513 (MYK 65).

[3] Jesko Fildhuth, Das byzantinische Priene, Berlin: DAI, 2017, 96-98; for an opposing view see Lohmann et al., Survey in der Mykale, I.284-290.

[4] Müller-Wiener, “Mittelalterliche Befestigungen,” 17-19.

[5] Urs Peschlow, “Latmos,” Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst 5 (1995): 695-696.

[6] Müller-Wiener, “Mittelalterliche Befestigungen,” 18-19.

[7] Theodor Wiegand, Der Latmos, Milet III.1, Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1913, 61-72.