If you haven't already done so, don't forget to read "Part 1" here first.

My previous post discusses the identification of Thomas Hoccleve’s handwriting in Christine de Pizan’s Epistre Othea and a glossary in London, British Library, Harley MS 219. This is only the second manuscript identified to date in which Hoccleve copies literary works by other authors.[i] The find is more striking when we consider the other contents of the manuscript and their implications for Hoccleve’s original compositions.

The major contents of Harley MS 219 are as follows:

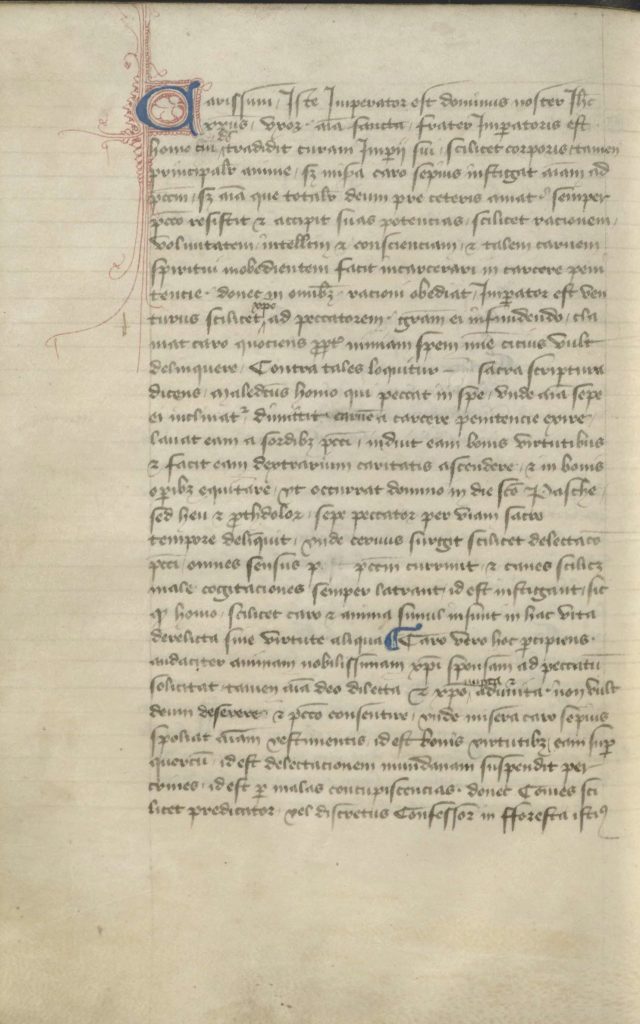

- Odo of Cheriton’s Fables in Latin, fols. 1r–37r.

- Selections from the Gesta Romanorum [Deeds of the Romans], in Latin, fols. 37r–79v.

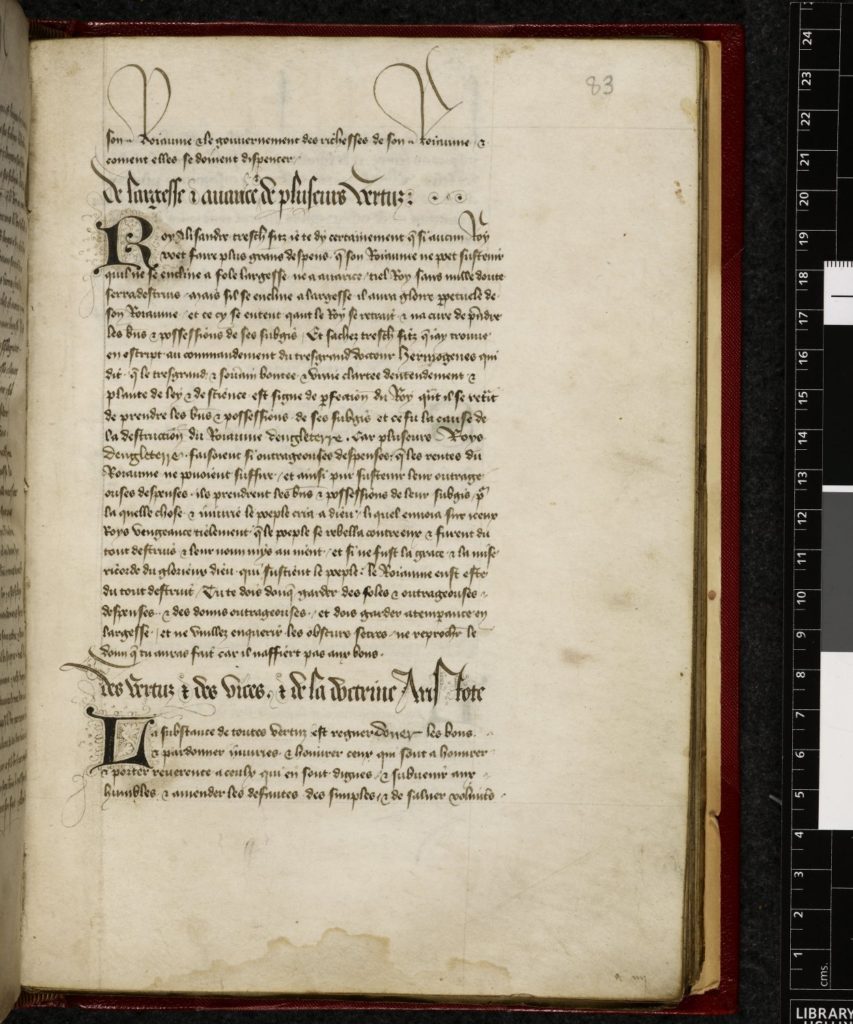

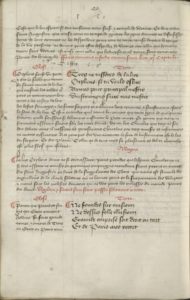

- An incomplete French translation of the Secretum Secretorum [Secret of Secrets, an advice text supposedly authored by Aristotle for Alexander the Great], fols. 80r–105v.

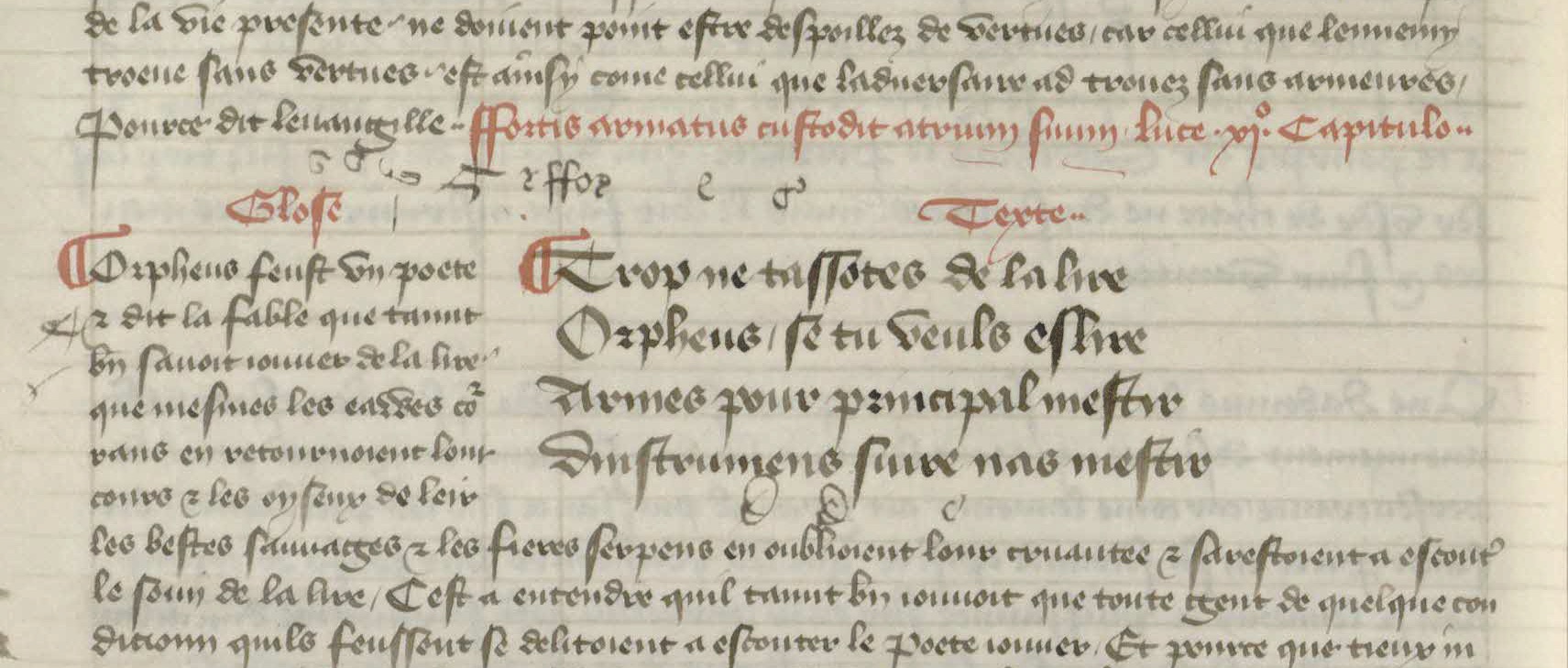

- Christine de Pizan’s Epistre Othea [Letter of Othea], French, in Hoccleve’s handwriting, fols. 106r–147r.

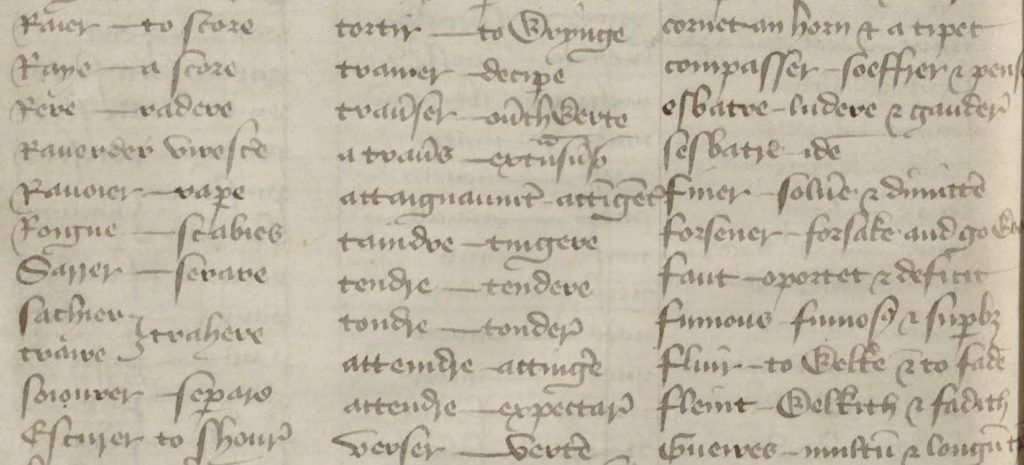

- A glossary of French terms translated into Latin and/or Middle English, in Hoccleve’s handwriting, fols. 147v–151v.

These are followed by items in later handwriting: A list in French of offices managed by the English Treasurer in later fifteenth-century handwriting (fols. 152v–153r); two English prayers, added in a sixteenth-century hand (fol. 153v); and a Latin recipe for the preservation of eyesight, added in a late fifteenth-century hand (fol. 154r).

Those familiar with Hoccleve’s poetry will recognize the Gesta as a source for two tales in Hoccleve’s Series– TheTale of Jereslaus’s Wife and The Tale of Jonathas– and the Secretum as a major source for the Regiment of Princes, an advice text Hoccleve dedicates to the future Henry V. For Hoccleve studies, one major question for both the Gesta and the Secretum has always been what form of the text Hoccleve used. In the case of the Gesta, there are a large number of manuscripts and almost innumerable variants among them that could have influenced Hoccleve.[ii] For the Secretum, the issue becomes one of language and then variable versions: did Hoccleve use a Latin version or a vernacular translation, and in either case, which one of many possible versions?

For me (and the reviewers of my original article manuscript), a crucial question was whether Harley MS 219 could resolve these uncertainties. The answer I found was yes, though not without much questioning of my eyesight and sanity, and some consultation with other scholars of Hoccleve’s handwriting. There are multiple scribes throughout Harley MS 219, and their handwriting is often excruciatingly similar. After all, when multiple professional scribes copied portions of a literary text that would be combined, they attempted to regularize their handwriting. The same aim of a more or less consistent handwriting across scribes would be valuable likewise in the Royal Office of the Privy Seal, where Hoccleve and – I think it likely – the other scribes in Harley MS 219 were employed.

As it turns out, Hoccleve does not copy the entire text of the Fables, Gesta, or Secretum. Instead, he copies at least one quire (bundle of pages) of the Fables and Gesta, he copies intermittent folios (pages) in the Gesta, and he provides corrections and annotations to the Gesta and the Secretum. The other scribes that copy the Fables and Gesta have very similar handwriting and demonstrate features common to Privy Seal scribes. The scribe who copied the Secretum displays stylized features – decorative strokes and flourishes – typically found in later handwriting, which would certainly seem to mark him as younger than Hoccleve. This scribe also leaves a blank when the French text indicts England for problematic politics, leaving it to his superior Hoccleve to decide whether to follow the French source and write England’s name in the space left (he does).

This unusual mode of copying and the corrections across the many sections of the volume suggest that Harley MS 219 may have been a collaborative volume produced by Hoccleve and his Privy Seal colleagues, perhaps even a training exercise for junior clerks under his supervision.[iii] Such an exercise might explain why Hoccleve often copies intermittent folios in the Gesta– to provide an exemplar for certain handwriting traits, not to share the copying of a lengthy text.

Now that we know Hoccleve copied, supervised, and/or corrected these texts, we have evidence of new and specific sources he knew. My preliminary work with the Gesta shows that the Harley MS 219 Latin tales do correspond to features of Hoccleve’s English compositions.[iv] We now also know that – although Hoccleve certainly could have read the Secretum in Latin – he had access to this French version, which he knew well enough to correct when the main scribe hesitated or went astray. This opens up new avenues for determining how these versions correspond (or do not) to Hoccleve’s English renderings, and we can also start to explore more seriously how the Fables and Othea may have influenced Hoccleve’s work. In other words, this manuscript allows us to compare Hoccleve’s works with these texts as sources and influences to see more specifically how he translated, adapted, and innovated within his English compositions.

The process of completing this research was not long by most standards (from discussion in summer 2018 to advanced publication in summer 2019), but it was intensely involved, as I put most other projects on the back burner and moved from focusing on Christine’s Othea to the glossary, to evaluating the scribal handwriting against known samples of Hoccleve’s, to evaluating all the convoluted and similar scribal handwriting in the other texts, and to investigating the broader implications for Hoccleve’s work and career.[v] There is still much work to be done to fully realize the importance of this manuscript, but I have, I hope, made a valiant start.

If lessons are to be learned here, I would suggest they are these: keep looking at “weirdo” manuscripts; follow the even odder threads within them that interest you; be open to working on something that isn’t your “main” project (with the caveat that if you do, it may take over your life); and, of course, when there is something about a manuscript bothering you, share ideas and images with friends. The generosity of our colleagues in the field of medieval studies – trusted friends, editors, anonymous readers, and colleagues with shared interests – is one of our greatest resources.

Misty Schieberle, PhD

University of Kansas

About the Author: Misty Schieberle is Associate Professor of English at the University of Kansas, currently completing an edition of the Middle English translations of Christine de Pizan's Epistre Othea and continuing her work on Harley MS 219, including an edition of the glossary.

[i]The first is the so-called ‘Trinity Gower’ in Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.3.2 (fols. 82r–84r), in which Hoccleve copies a few folios of Gower’s Confessio Amantis. There may be another, according to Linne Mooney, whose work is forthcoming.

[ii]On which, see Philippa Bright, The Anglo-Latin Gesta Romanorum(Oxford, 2019).

[iii]On Hoccleve’s supervisory role from c. 1399-1425, see Linne R. Mooney, ‘Some New Light on Thomas Hoccleve’, Studies in the Age of Chaucer29 (2007), 293-340, at 297-99.

[iv]See Roger Ellis, ed., Thomas Hoccleve: ‘My Compleinte’ and Other Poems(Exeter, 2001), 263-68, who reconstructs from Hoccleve’s English and various Latin manuscripts (not including Harley MS 219) readings likely to have been in Hoccleve’s source for the Tale of Jereslaus’ Wife.

[v]See Schieberle, “A New Hoccleve Literary Manuscript: The Trilingual Miscellany in London, British Library, MS Harley 219,” Review of English Studies(forthcoming November 2019), currently available online for advanced access subscribers: https://academic.oup.com/res/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/res/hgz042/5510111

To address this theme,

To address this theme,  In a paper on “Navigating the Gospel: Nonlinear Access and Practical Use,”

In a paper on “Navigating the Gospel: Nonlinear Access and Practical Use,”  Practices of reading and access are embedded in larger discourses. In his paper on “The Gospel Read, Sliced, and Burned: The Material Gospel and the Construction of Christian Identity,”

Practices of reading and access are embedded in larger discourses. In his paper on “The Gospel Read, Sliced, and Burned: The Material Gospel and the Construction of Christian Identity,”