The Froissart Harley, Harley MS 4379, is a manuscript filled with popular conceptions of the medieval period: knights, jousting, courtiers, war, queens and kings. Harley MS 4379 consists of the fourth volume of Froissart’s Chronicle, which recounts the events of the Hundred Years’ War. The manuscript was produced between 1470 and 1472 at the behest of Philippe de Commynes, one of the most powerful members of Charles the Bold’s court.

Froissart’s Chronicle explores courtly life, the sphere of the nobility, but his work also teaches noble listeners: it includes emblematic examples of good, contemporary rulers, meant to advise a young lord in the proper governance of his subjects.

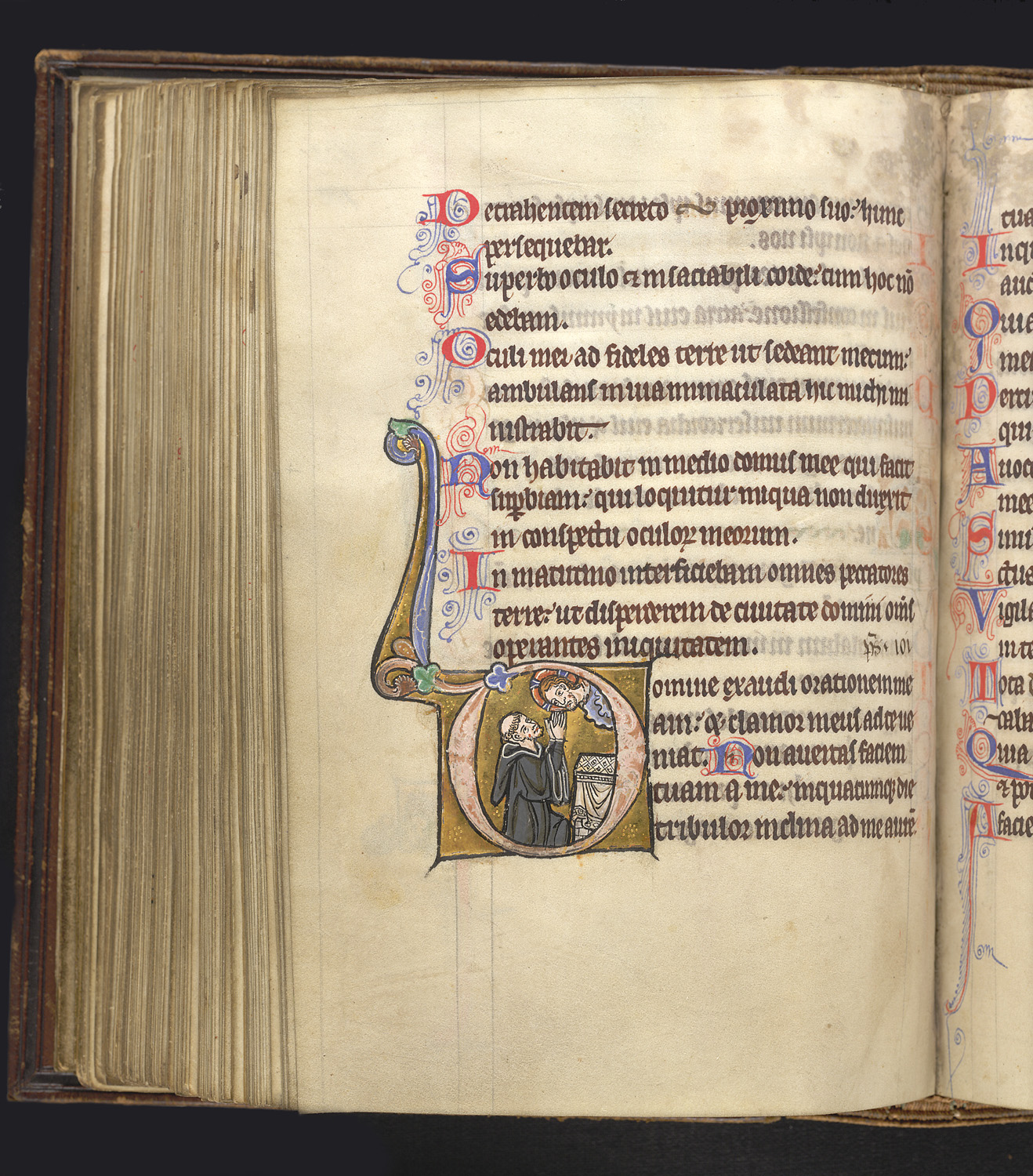

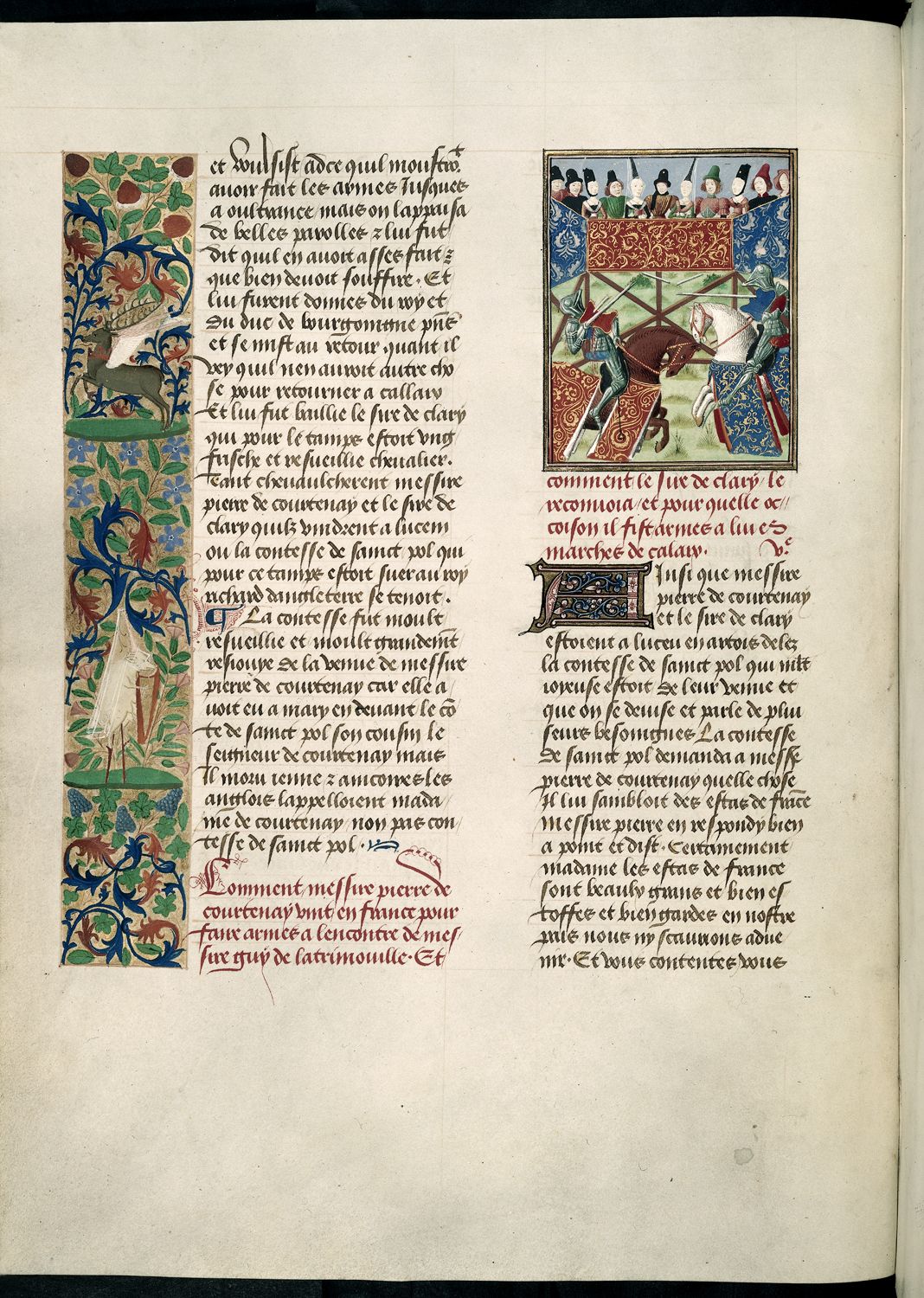

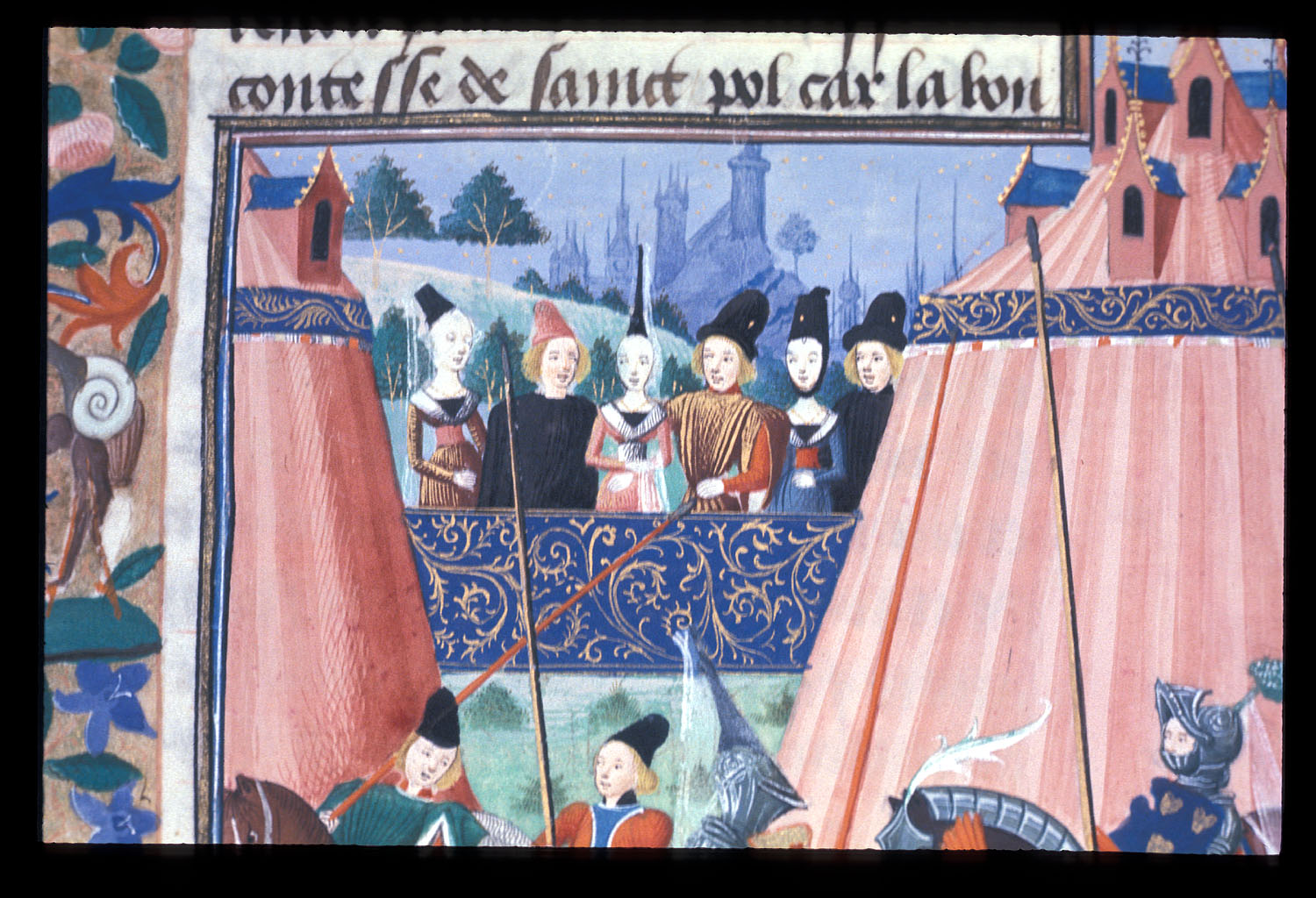

Although the text itself instructed its readership in proper chivalric behavior, the illustrations and marginalia enliven dry discussions of events such as siege warfare and provide images to connect to the chapter text. One particularly interesting feature of Harley MS 4379 centers on the depictions of animal marginalia and how they relate to the text.

Any medieval reader would have comprehended allegorical associations with animals. One notable example of such symbolism occurs in the hunting scene in Fit 3 of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. While Gawain remains in Bertilak’s castle with Bertilak’s wife, his host hunts for three days: the first day he hunts deer, the second a boar, and the third a fox. The alternating hunting scenes and bedroom scenes narrated in Fit 3 parallel one another, underlining the analogous relationship between his lady’s attempts to trick Gawain and the Bertilak’s attempts to catch his prey.

However, the animal symbolism in the Froissart Harley differs from the hunting scenes in Gawain in an obvious fashion. While Gawain’s animals are meant to reinforce Gawain’s perilous situation, the marginalia in the Froissart Harley seem to caricature their own text. Regarding the rabbit and snail jousting, neither animal symbolically represents the jousting knights in the center miniature, nor do these two animals have a broader meaning in medieval bestiaries concerning jousting. These marginalia are meant to represent and enhance the text they accompany, but this point is problematic when considering the Burgundian approach to chivalry, the milieu out of which this manuscript emerged. Burgundians valued chivalric ideals above all else, as is shown by the great status granted to those of the Order of the Golden Fleece, a knightly order created by the dukes of Burgundy. Associating a rabbit and a snail with the jousters of Inglevert, perhaps the most vibrant and epic tournament in Froissart’s Chronicle, most likely would not have pleased a Burgundian audience.

Nor does the Master of the Froissart Harley spare courtly women in his caricatures. On the margin of folio 19v, the illustrator places a sow on stilts wearing a conical hat, playing the harp. This sow draws attention to the miniature of female courtiers, all wearing conical hats on watching the tournament in the middle of the page. Again, this characterization is paradoxical in a Burgundian context: pigs typically represented uncleanliness and greed, unfortunate traits for a woman trying to navigate the vicissitudes of court.

Sean Sapp

PhD Candidate

Department of History

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of an ongoing series on Multimedia Reading Practices and Marginalia: Medieval and Early Modern

Further Reading:

Froissart’s Chronicle trans. John Jolliffe (New York: Random House, 1968).

Susan Crane, Animal Encounters: Contacts and Concepts in Medieval Britain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

Laetitia Le Guay, Les princes de Bourgogne lecteurs de Froissart : les rapports entre le texte et l’image dans les manuscrits enluminés du livre IV des Chroniques (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998).

Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe (Los Angeles: Getty Pulications, 2003).

Willene B. Clark, A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation (Boyden Press, 2013).

http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/09/knight-v-snail.html