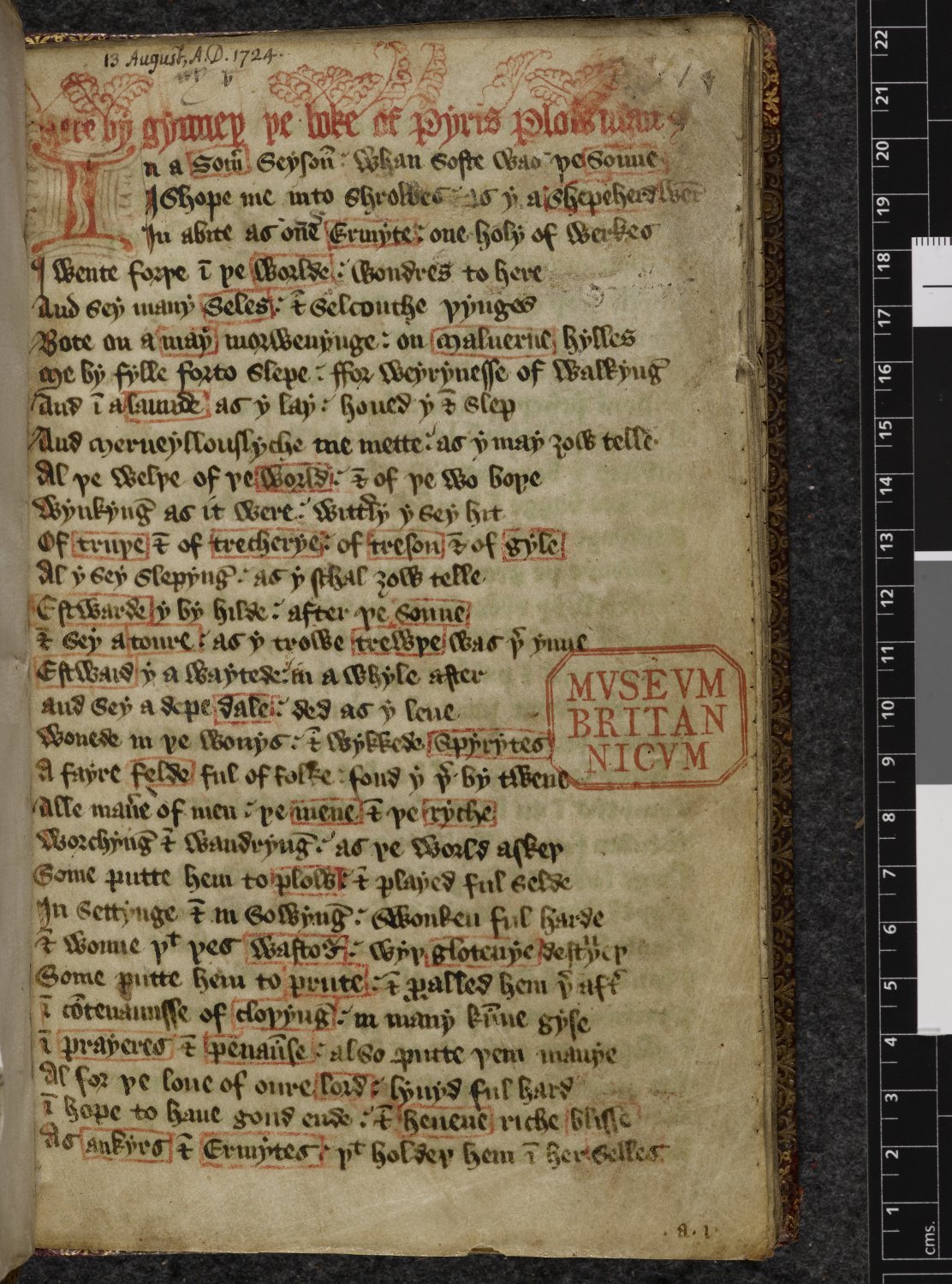

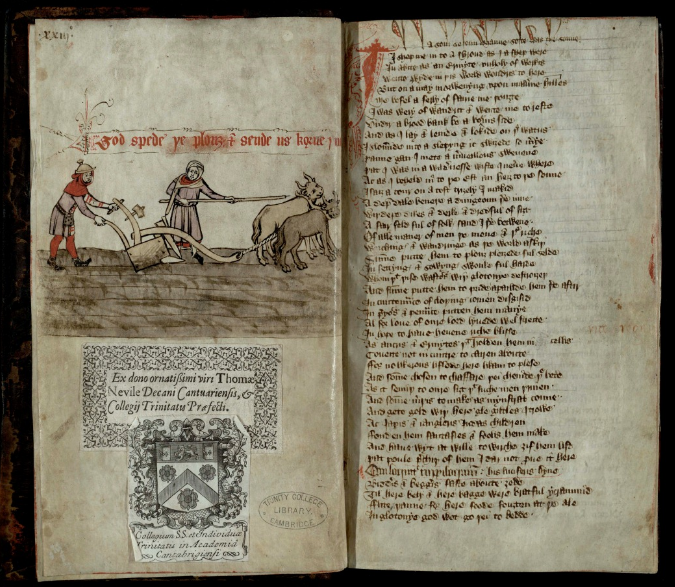

Answering the who, what, where, when, and why of a medieval manuscript can be like trying to solve a who-done-it without that convenient answer key supplied by the author. Imagine then, that the same who-done-it exists in fragments. Such is the case of the 14th century work Piers Plowman, composed by William Langland in several successive stages and extant in not one, not two, not three, but four versions which vary significantly in length and sometimes content: the A-, B-, C-, and Z-texts. Scholars have been debating the relation between the first three versions of the text for well over a century, and with the discovery of the Z-text in the 1980s the conversation became even more complex. The Z- text is of greatly contested authorship and complicates our understanding of Piers Plowman as a radical, reform-minded text.

The A-, B-, and C- texts (c. 1370, 1378-9, and 1386 respectively) are widely regarded as the work of a single author, William Langland, who appears as the main character Will in the text. Will falls asleep in the Malvern Hills, lulled by the sweet trickle of a nearby stream, and enters the world of Christian allegory. As the work unfolds, we can see Langland’s deep concern for the state of Christianity and the corruption which could destroy its true tenets. Many scholars view Piers Plowman as a work highly appealing to the followers of John Wyclif, an Oxford philosopher and theologian who called for Church reform, arguing against what he regarded as the worldliness of the medieval Church and notably denying the doctrine of transubstantiation as his views progressed; Wyclif also argued for lay access to vernacular scripture, condemned the papacy and the Church hierarchy (particularly monasticism), and denied the validity of the cult of the saints. He highly esteemed evangelical poverty and criticized the Church’s failure to adhere to this ideal. In Piers Plowman, William Langland displays a great concern for the plight of poor, hard-working Christians who often suffer because of the opulence and corruption of the higher classes of aristocrats and clerics.

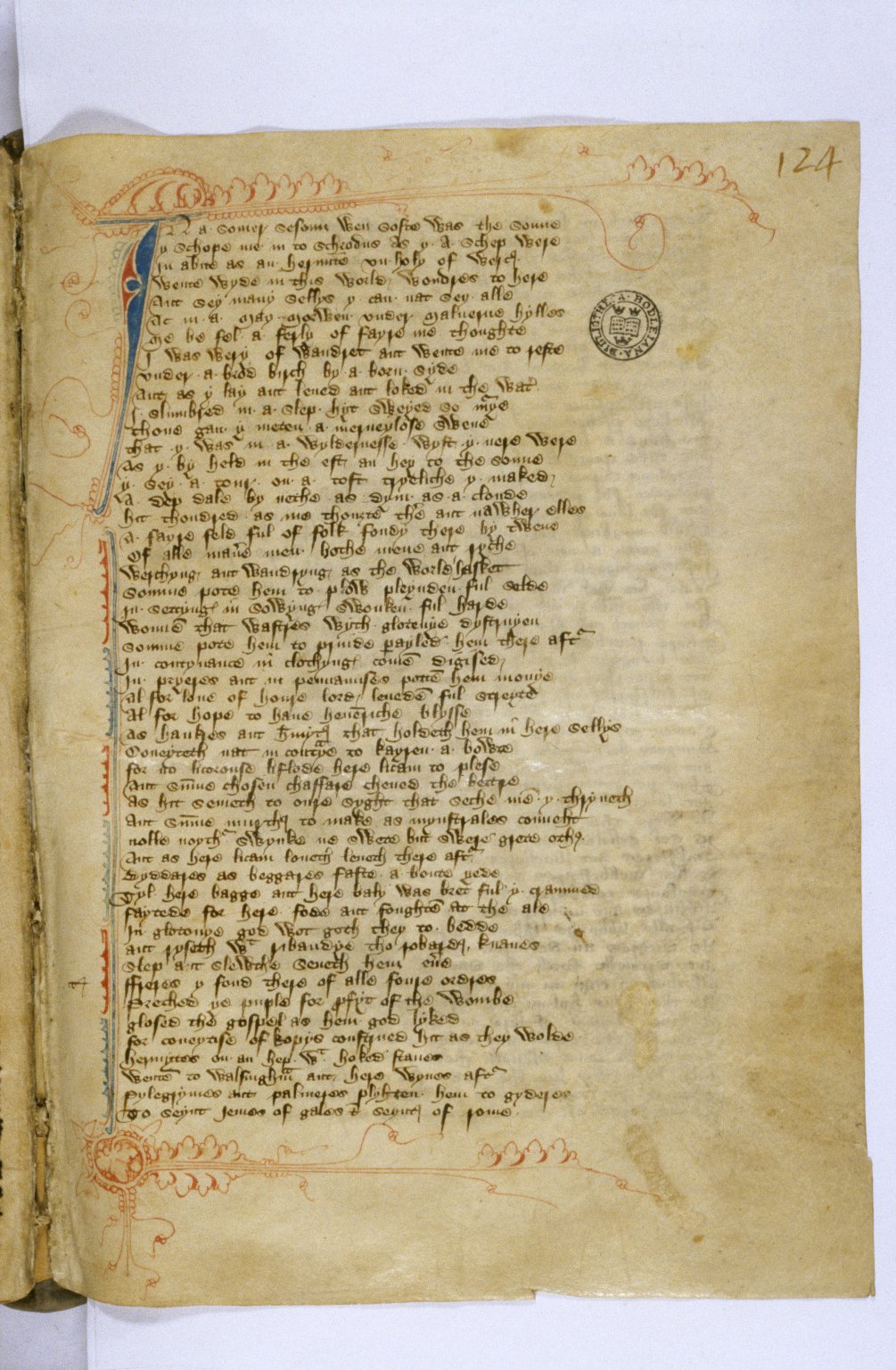

Within the Z-text of Piers Plowman, found in MS Bodley 851, we can find an inscription which identifies the manuscript as the property of Brother John Wells, a Monk of Ramsey. We have a likely candidate for the identity of this John Wells, namely, an Oxford scholar and opponent of Wyclif. To add another layer of intrigue, Wells is also the satirized subject of a pro-Wycliffite macaronic verse published on a broadside in 1382 which appears to refer to Piers Plowman (see Kerby-Fulton, “Confronting the Poet-Scribe Binary,” 498-499). What is an active opponent of Wyclif doing with a manuscript of Piers Plowman included in his personal anthology?

In fact, recent scholarship has pointed to the author of the Z-text as an enthusiastic imitator of Langland rather than Langland himself. Significantly, the Z-text contains several passages portraying very orthodox views on the sacraments which are less prominent in other versions of Piers Plowman. For example, in a very orthodox move, the Z-text uniquely contains these lines highlighting the importance of the mass and the Eucharist:

[God’s word] maketh the messe ant the masse that men vnderfongeth / For Godus body ant ys blod, buyrnes to saue

(Passus Quintus, ll.37-38).

Lines such as these may point to the creator of the Z-text as one who greatly admired Langland’s work, but who sought to add moments into the text which reinforce the orthodox view of the centrality of sacraments in the medieval church. Analyzing moments such as these may bring us closer in solving this medieval who-done-it, and I hope to explore this issue in future work.

Maj-Britt Frenze

PhD Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Works for Further Reading:

Fuller, Karrie. “The Craft Of The ‘Z-Maker’: Reading The Z Text’s Unique Lines In Context.” The Yearbook of Langland Studies 27 (2013): 15–43.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. “Confronting the Scribe-Poet Binary: The Z Text, Writing Office Redaction, and the Oxford Reading Circles.” In New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices: Essays in Honor of Derek Pearsall, edited by Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, John J. Thompson, and Sarah Baechle, 489–515. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. “Piers Plowman.” In The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature, edited by David Wallace. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Rigg, A.G. and Charlottes Brewer, Ed. Piers Plowman: The Z Version. Toronto: PIMS, 1983.