When you first learned how to read and write, you probably did so in your native language. As natural as this seems, medieval teachers did things differently. Throughout most of the Middle ages, grammar meant Latin grammar; literate, able to read Latin. Ælfric’s Grammar (written ca. 992-1002), marks an important break with previous pedagogy. In the first sentence Ælfric proclaims the revolutionary nature of his project: “I’ve worked to translate these excerpts from Priscian for you boys into your own language” (he does so in Latin, ironically enough). For the first time, then, a European vernacular was used to teach grammar.

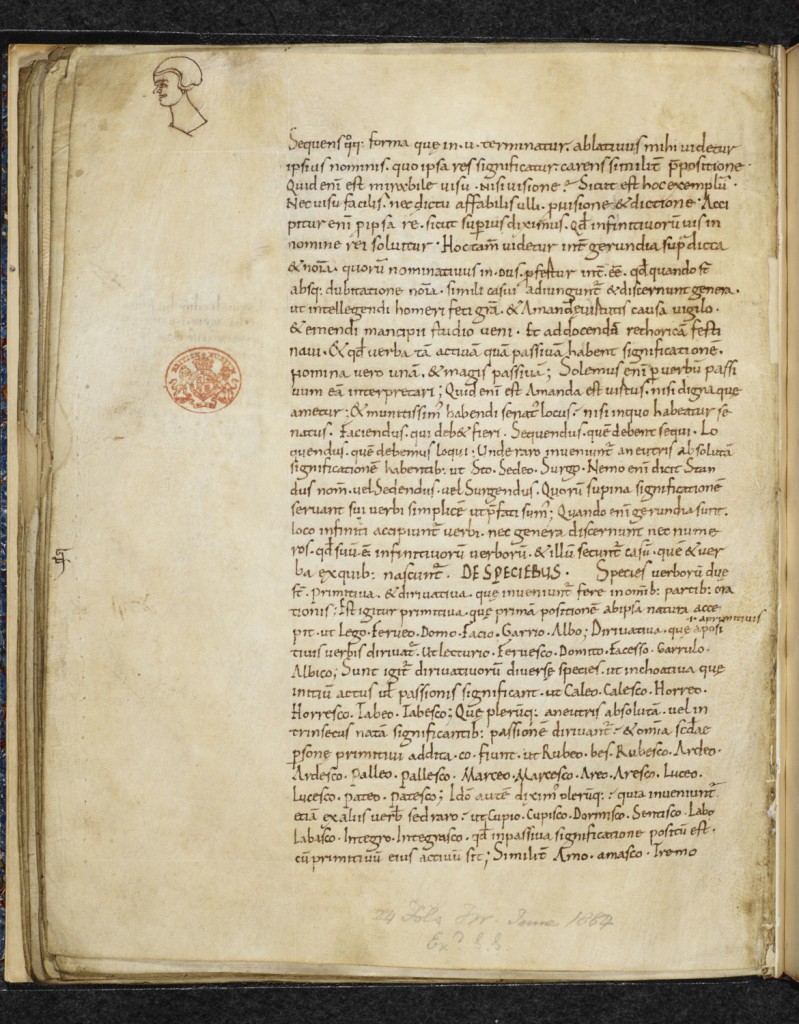

Ælfric’s source is the Excerptiones de Prisciano, a judicious culling containing “almost all the important and interesting components” (David W. Porter, ed., Exerptiones de Prisciano, Woodridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002) from the Latin grammarian (fl. 500) whose textbook was a virtual best-seller in medieval Europe. The Excerptiones survives in only two complete manuscripts: London, British Library MS Add. 32246 and Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Nouv. Acq. Lat. 586. The former (pictured below), written in the first half of the eleventh century, is particularly noteworthy for the Latin-English glossaries that often crowd its margins (when there isn’t a random peasant’s head there instead).

It thus offers us a fascinating view of how medieval students in England could negotiate between Latin and their native tongue. The glosses in Add. 32246 were intended to help students cope with difficult Latin words by giving English definitions. They’re no less useful today, only now, when our collective knowledge of Latin greatly surpasses our knowledge of Old English, for the exact opposite reason: using Latin to improve our understanding of Old English. For scholars of Old English, who most often determine the shades of meaning of a word based on its usage in a very small corpus, the glossaries provide priceless linguistic information.

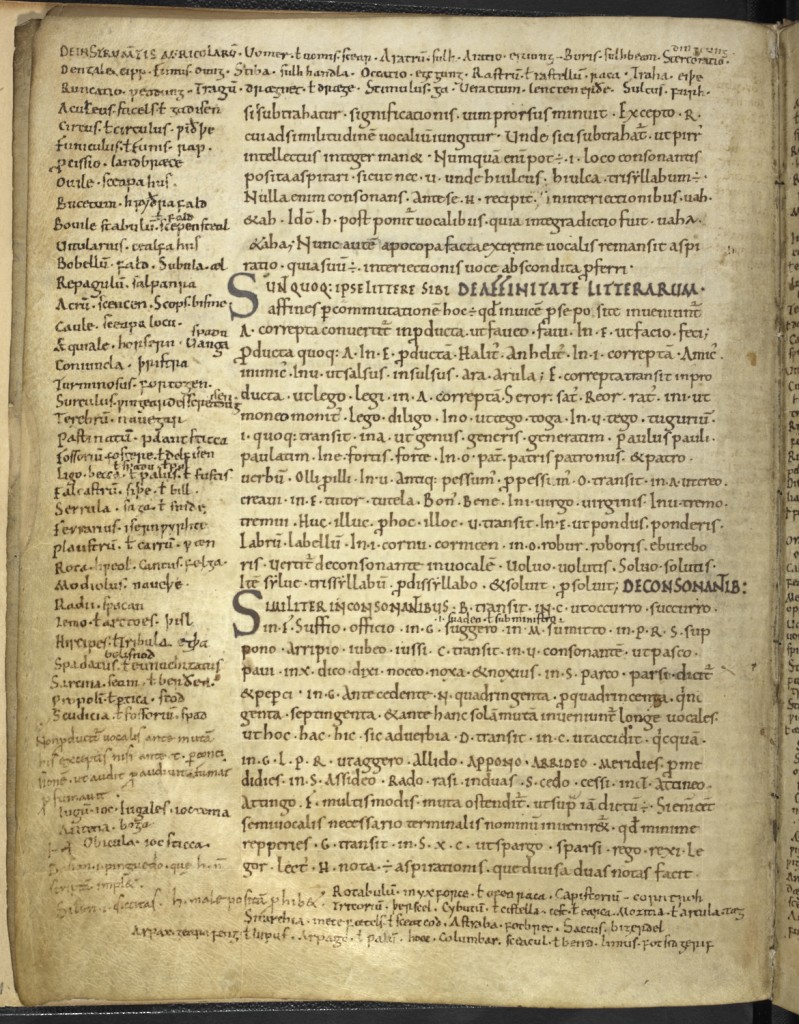

This particular folio contains a list of farming tools, as indicated by the majuscule heading in the top left corner: “DE INSTRVM(EN)TIS AGRICOLARV(M).” The format is simple with a period separating the Latin word on the left from its English equivalent. On the next line, we can see that Dentale (a plowshare’s beam) is cipp and Fimus (manure) is dung. At times two Latin synonyms are provided for one English word, or vice-versa. Thus, on the fourth line in the left margin Aculeus (spur) is translated as stiels. ł (an abbreviation for vel, “or”) gadisen. While the glosses aren’t directly related to the text, which at this point treats “the relationship of letters” (DE AFFINITATE LITTERARUM) and “consonants” (DE CONSONANTIBUS), it reflects a preoccupation similar to Ælfric’s, i.e. combining Latin grammar and English vocabulary aids .

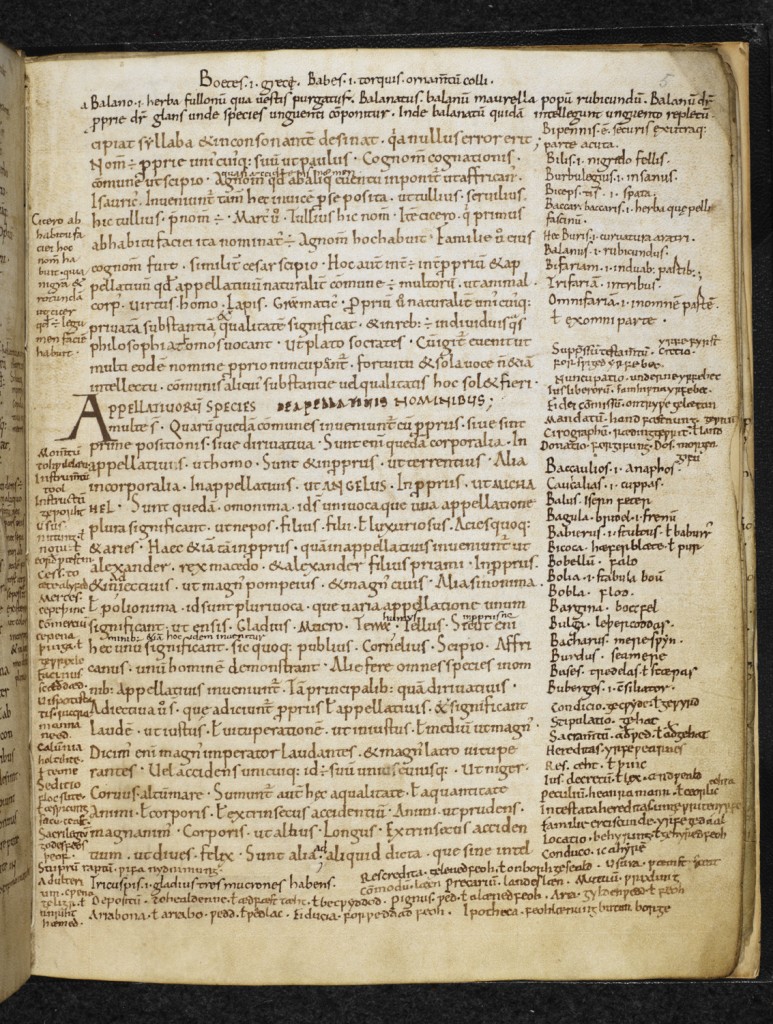

At the top of folio 5r, we find another set of glosses written in a different hand. These glosses, sorted by letter (this page features “B”) but not in alphabetical order, define exceedingly obscure Latin words through more common ones.

Thus, at the top we see Boeties i. greci (“Boeotians, i.e., Greeks”), and on the line below, a Balano i. herba fullonu(m) qua uestis purgatus (“Balano, i.e., a fullonum herb that cleans clothes”). On the right margin, our other scribe has continued his Latin-English glossary of agricultural terms, now imitating the alphabetical order of the Latin-Latin list.

Garrett Jansen

University of Notre Dame