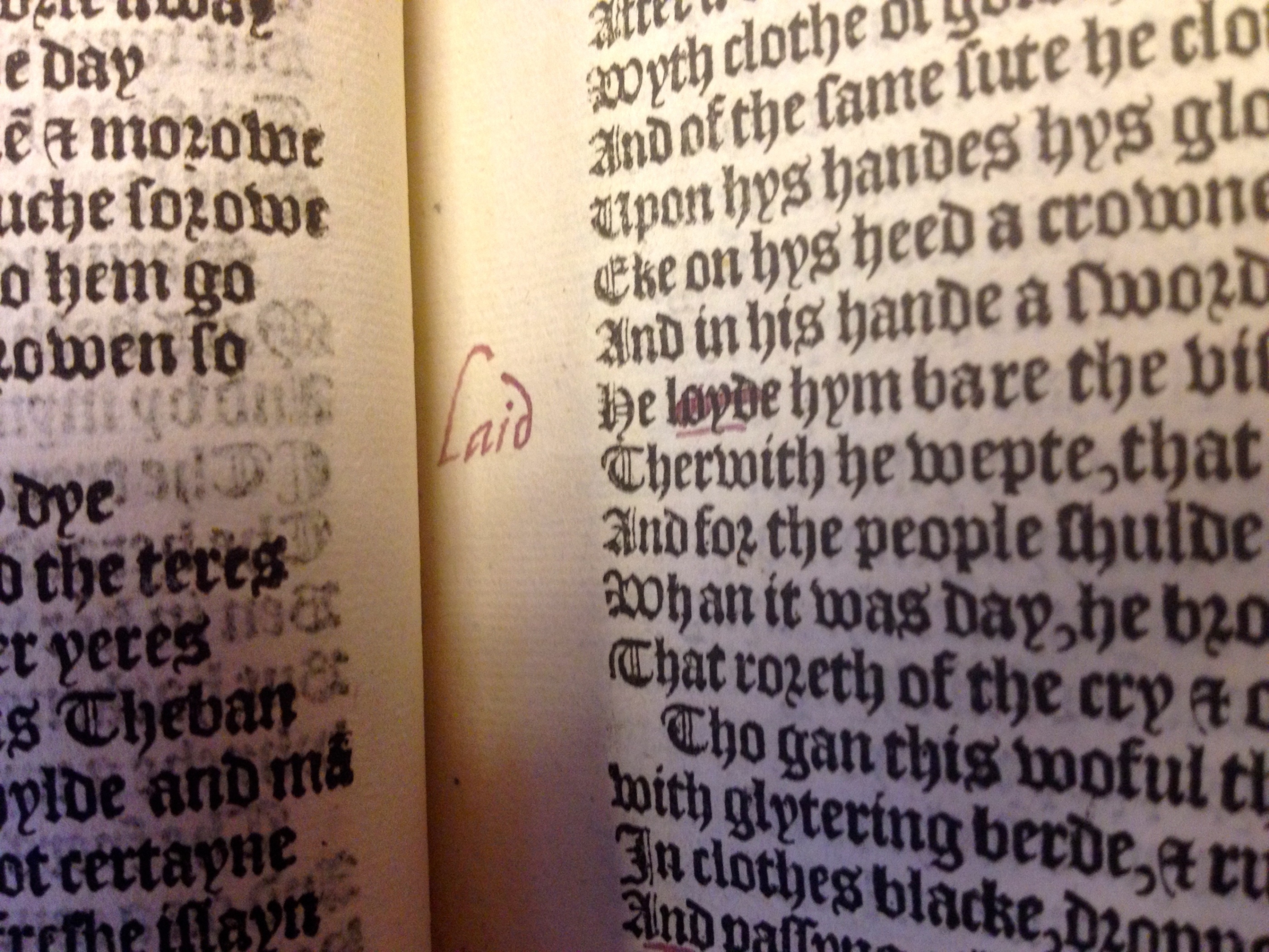

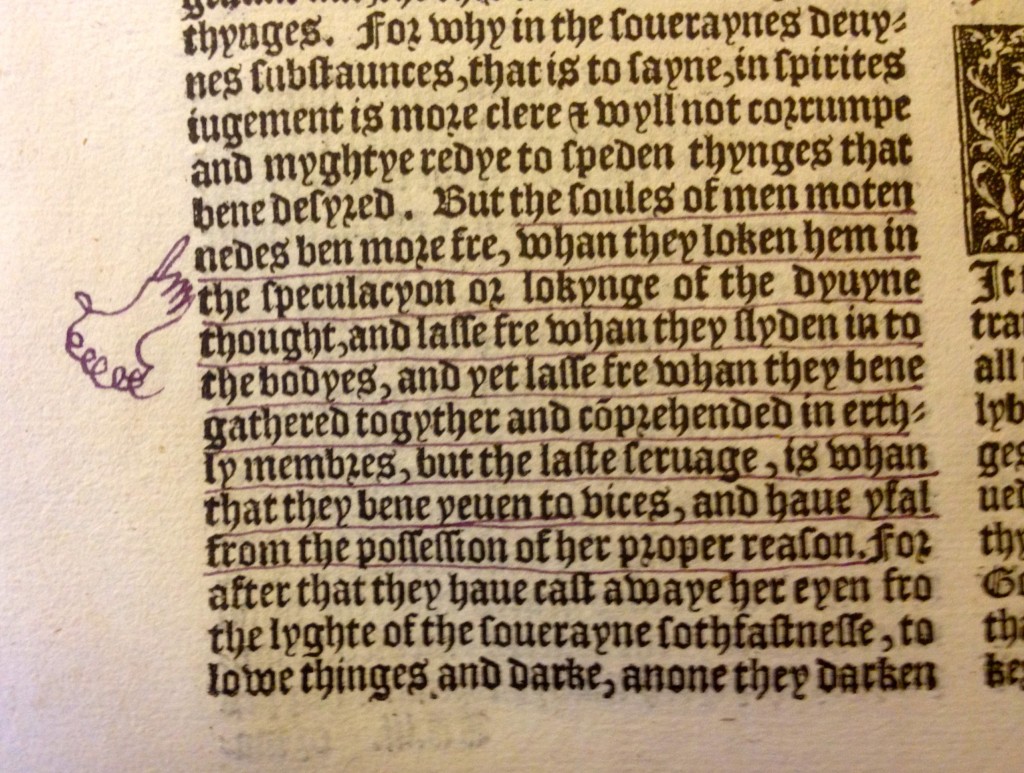

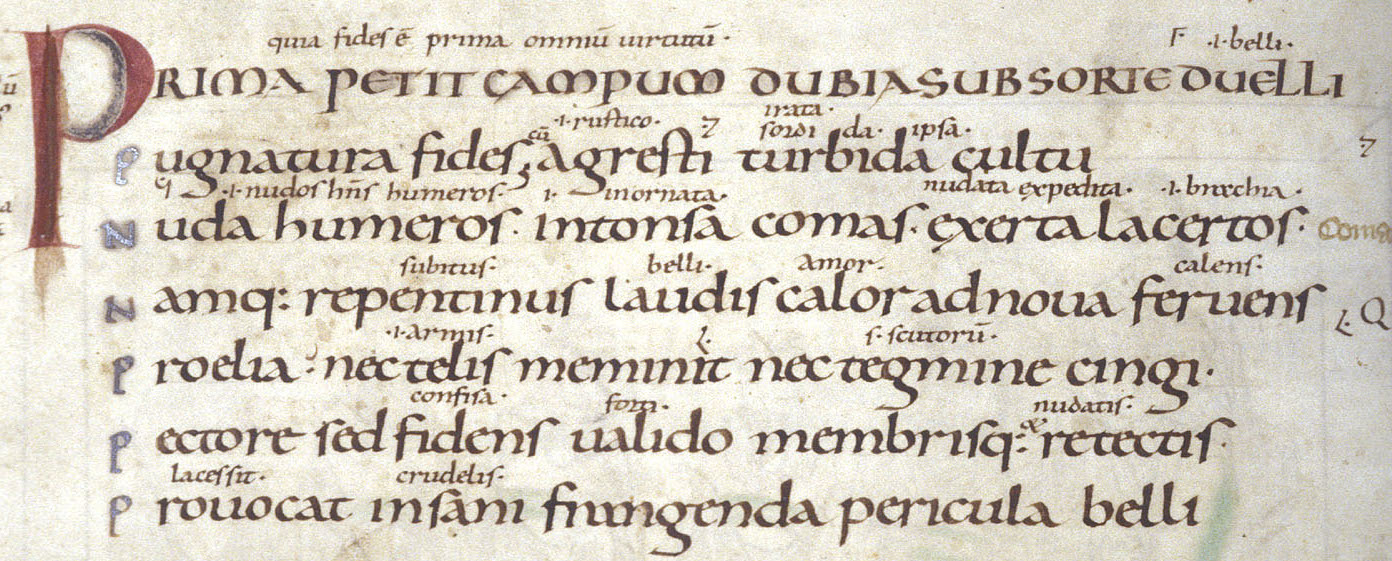

When looking at medieval manuscripts for the first time, one might notice smaller words inserted between the lines of the primary text. Called interlinear glosses, this type of addition can be divided into two kinds: lexical and suppletive. The former typically provides explanations of difficult vocabulary, while the latter might explain a point of grammar. Unsurprisingly, they were useful for students who were learning Latin [i], as glosses might explain a challenging turn of phrase or a grammatical sticking point. Although many were added in Latin, they might be written in any number of other languages. The Lindisfarne Gospels, a famous manuscript from the early 8th century, has Old English glosses added by Aldred, provost of Chester-le-Street in the 10th century.

While interlinear glosses can provide information about the language mechanics of the primary text, they can also direct the reader’s attention and shape comprehension of the selection at hand. The introduction of definitions and sentence scaffolding can alter the reader’s experience, potentially producing a new understanding of the central text.

Glosses, as opposed to some instances of impulsive marginalia, were rarely spontaneous [ii], but were typically added to a volume and included in subsequent copies. On some occasions, the scribe copying the manuscript might mistake an interlinear gloss for part of the main text and reproduce it in the body of a new document [iii], an error which can even survive into subsequent translations [iv].

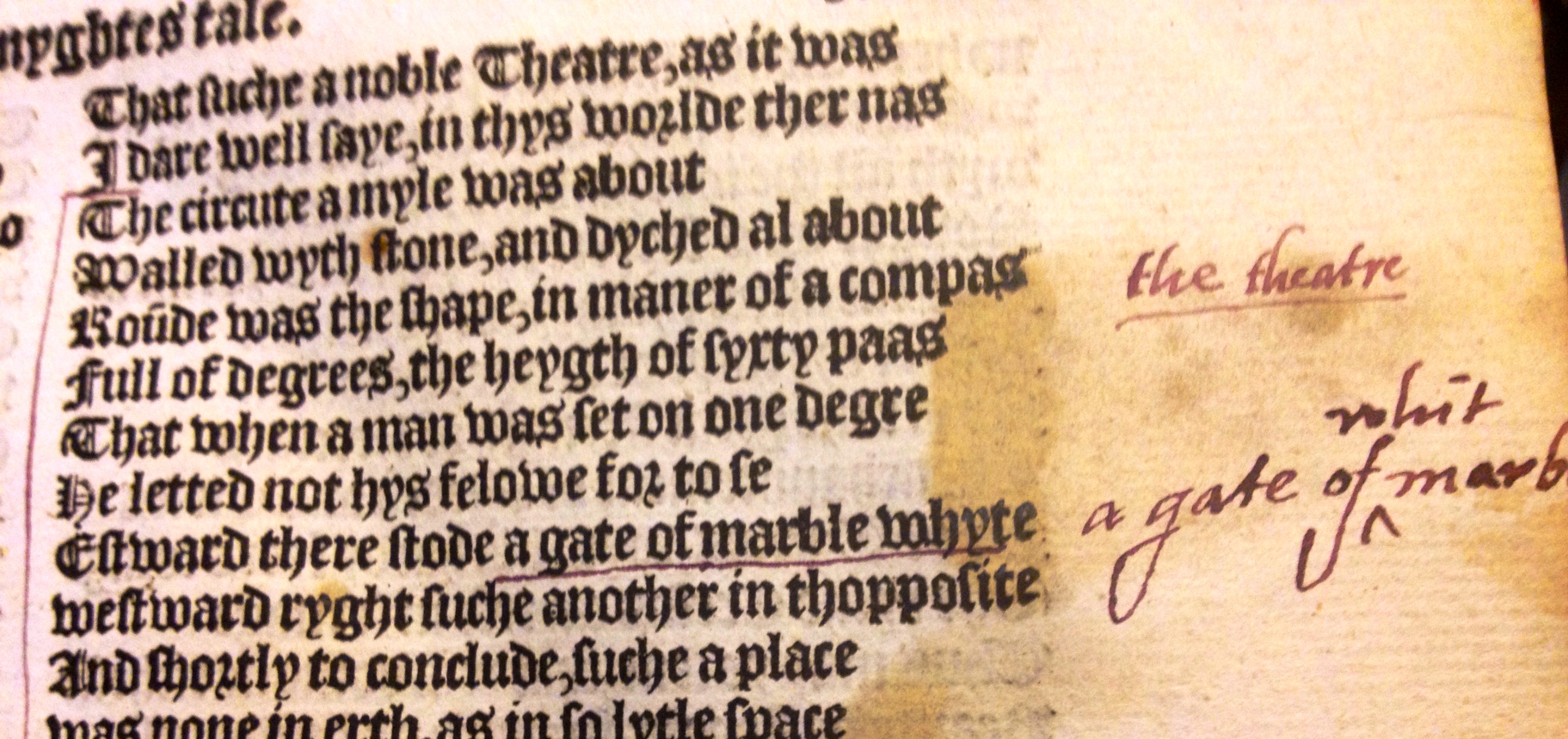

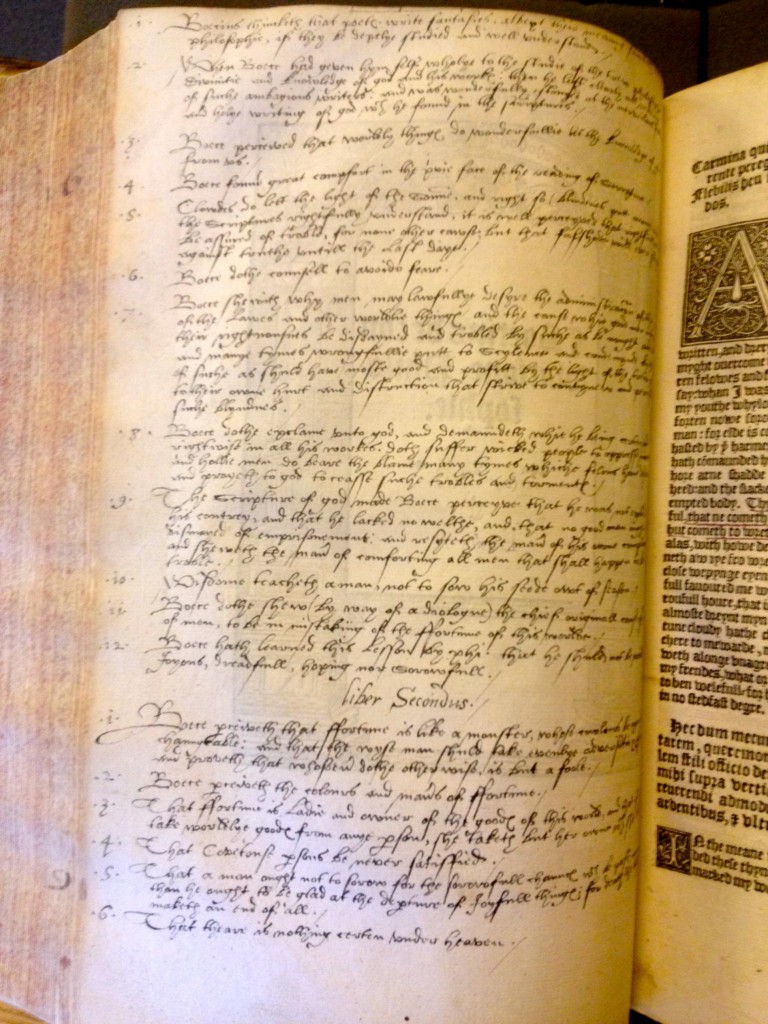

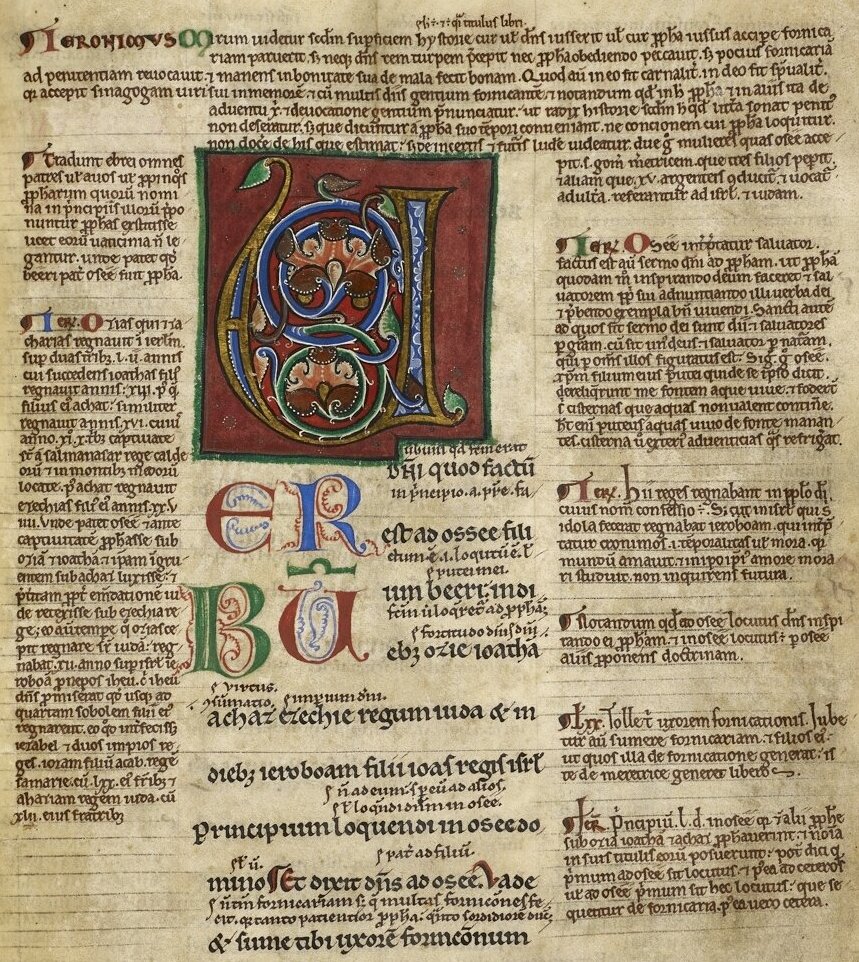

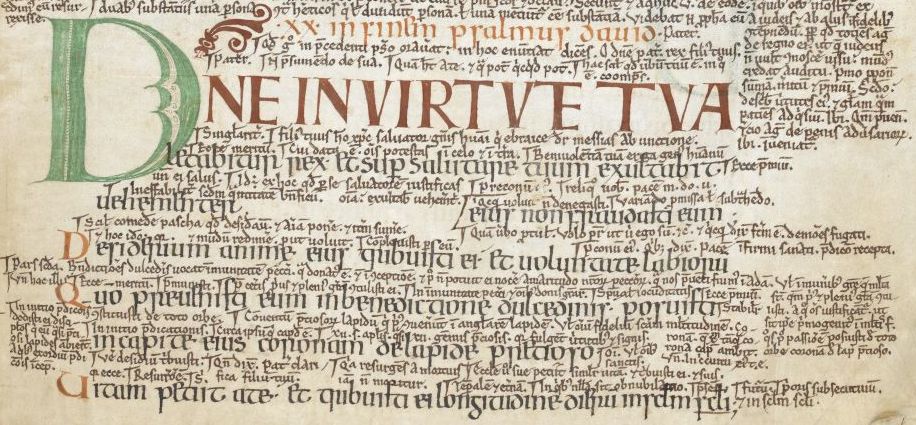

In addition to interlinear glosses, a text might share the page with a commentary, granting the reader access to critical interpretation as they progress. Commentaries were not limited by genre and could be composed for many different types of texts, from poetry to theology. Although early manuscripts may have been more simply formatted, by the Carolingian period, the page was being fashioned with one column for the primary text and a second for the commentary [v]. The side-by-side layout allowed readers to shift back and forth between the base text and the critical interpretation without having to retrieve other books (which may not have been readily available). By the twelfth century, the Glossa ordinaria by Nicholas of Lyra, which features an even further integrated format [vi], was becoming the authoritative biblical commentary [vii].

For the 21st century reader, the sheer amount of text might seem overwhelming at first, but following the hierarchy of scripts, one can sort out the interlinear glosses and commentary from the foundation text. In the example above from BL Harley MS 1700, the reader can start with the largest letter: an illuminated “U”. This introduces Uerbum (“word”) which becomes the first word of the verse and forms the beginning of the biblical passage. The widely spaced text allows the interlinear gloss to be written between the lines in a smaller hand. The large text blocks around the central section form the commentary and provide a close reading of the biblical text, proceeding line by line and word by word.

Beyond providing close readings, detailed explanations, and citations for related materials, commentaries were enormously influential in the understanding and translation of texts into the vernacular. Their content even impacted the work of contemporaneous vernacular authors [viii]. By understanding that glosses and medieval commentaries were often integrated with a text, some of the resources and habits of medieval readers come into focus. Attention to exegesis and the resulting proliferation of commentaries ensured that many readers would have encountered these critical tools and their impact on translation and interpretation was widely felt. The commentaries and glosses which survive in manuscripts (but are infrequently included in modern print editions) provide present-day scholars context that can shape how reception and reading cultures are understood. As noted by Alastair Minnis in his book Medieval Theory of Authorship: Scholastic Literary Attitudes in the Later Middle Ages, “One might go so far as to say that it is the original text together with its accompanying commentary… that should be regarded as the source.”[ix]

Kristen Herdman

MA Student

Department of Classics

Case Western Reserve University

Notes:

[i] F. A. C. Mantello and Arthur George Rigg. Medieval Latin: an Introduction and Bibliographical Guide. (Washington DC: The Catholic University of America Press,1999), 95.

[ii] Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 39.

[iii] Ibid., 39

[iv] Ralph Hanna, Tony Hunt, R.G. Keightley, Alastair Minnis, and Nigel Palmer, “Latin commentary tradition and vernacular literature” in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Vol. 2, Vol. 2. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005), 364.

[v] Bernhard Bischoff, Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages. (Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1990). 28.

[vi] Ibid., 217.

[vii] Rafey Habib. A History of Literary Criticism and Theory: From Plato to the Present. (Malden, Mass: Blackwell Pub, 2008), 176.

[viii] Alastair Minnis. Medieval theory of authorship: scholastic literary attitudes in the later Middle Ages. (London: Scolar Press, 1987), xxix.

[ix] Ibid., xxx.