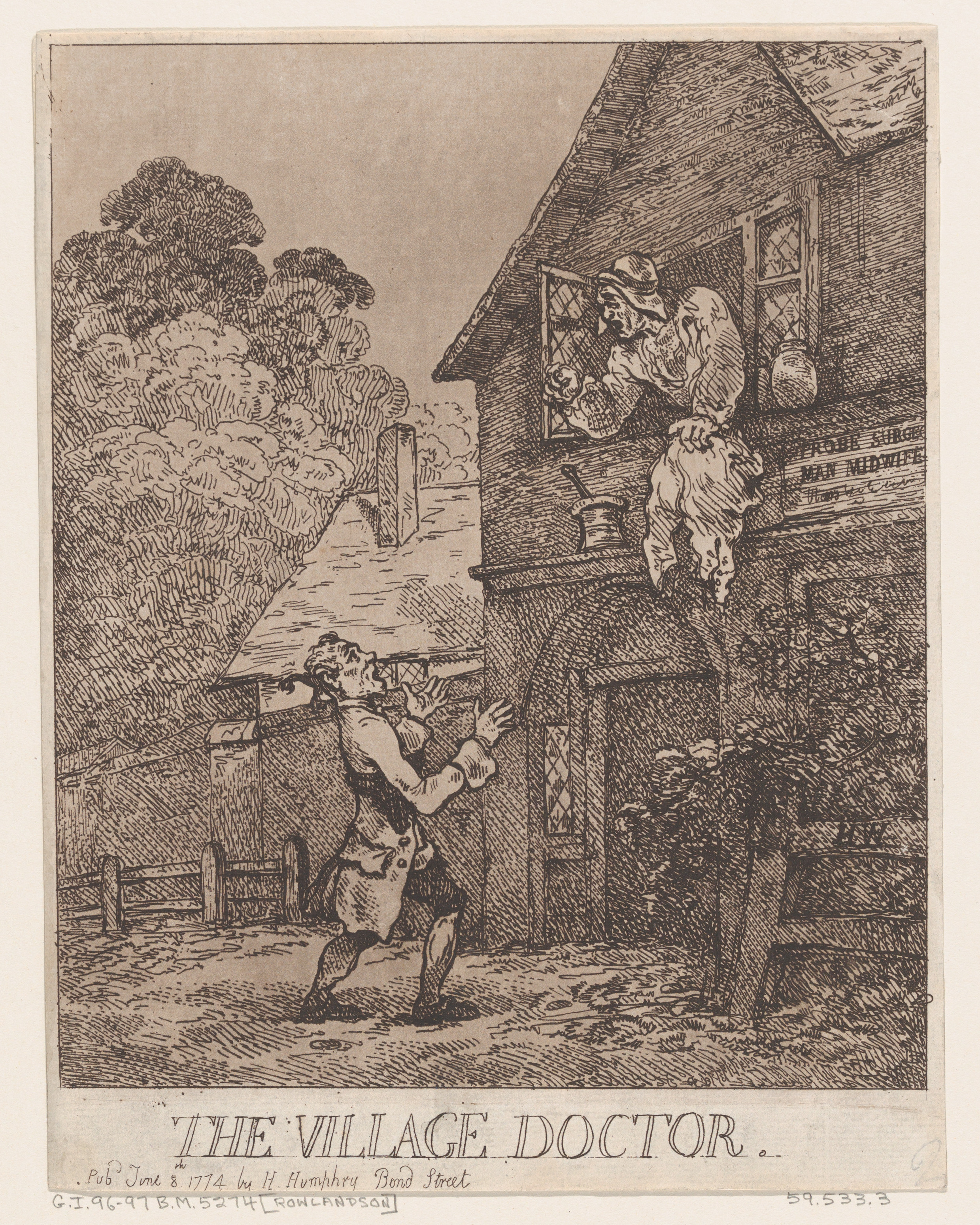

In their 2013 guide to help physicians curate their online personas, Kevin Pho, M.D., and Susan Gay tell the story of a doctor who, upon Googling herself, finds out that she shares her name with an optometrist accused of deliberately blinding patients. In the age of WebMD, Twitter, and online rankings, the challenges of managing both one’s reputation and the endless stream of misinformation permeating the web have generated new ways of talking about medicine and its practitioners. Skepticism of medical doctors, however, has been around since long before the profession was recognized as such.

The standardization of technical medical training in universities was a late development in the Middle Ages, in part because many academics considered the activities of wise women and barber surgeons to fall below the study of Aristotelian natural philosophy, astrology, and religious council. Even after universities across Western Europe began teaching hands-on medical procedures, they struggled to obligate patients, including aristocratic and royal patients, to rely exclusively on those with degrees. Well into the fifteenth century, it was inconceivable to mandate that English medical professionals be university-trained. This was because, first, the institutions that gave out these credentials in England, Oxford and Cambridge, were far removed from the most populated areas like London. Second, these urban communities were far too vast to be served by the handful of medical graduates.

The works of two major fourteenth-century authors demonstrate that the skepticism and ridicule with which doctors are often treated to this day existed even as the occupation of the medical professional was still being defined. In his “General Prologue” to the Canterbury Tales, for instance, Geoffrey Chaucer heavily satirizes his Physician, who knows little of the Bible, dresses extravagantly, and reaps financial rewards from the plague. A trained alchemist, he uses his claimed expertise in the scientific properties of gold to benefit from its economic value: “For gold in physic (medicine) is a cordial,/ Therefore he loved gold especially” (1.443-44). Like so many of Chaucer’s professional academics in the Canterbury Tales, the Physician abuses his qualifications in order to line his pockets.

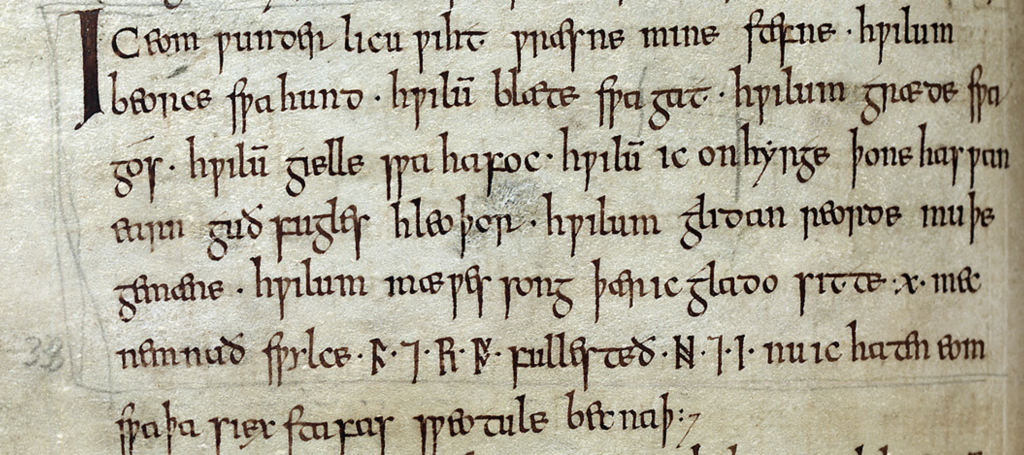

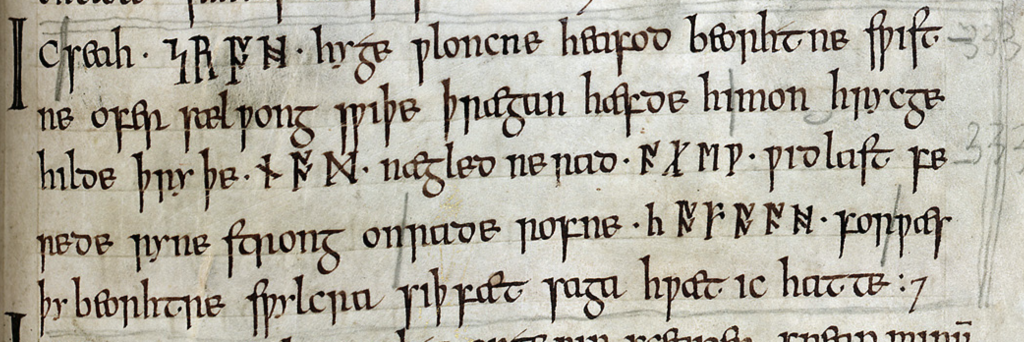

William Langland’s B text of Piers Plowman anticipates the “General Prologue”’s criticism of the Physician. In the last passus, the personification Life seeks out a “phisik” to cure him of Old Age (B.20.169). The “Physician with a furred hood,” to whom Life gives gold “that gladdened his heart,” is similar to Chaucer’s Physician in that, in his greed, he takes advantage of Life’s illness. He plays a greater role in Langland’s allegorical theology when it becomes clear that his craft obscures the need for spiritual healing. The “glass helmet,” or placebo, that he offers Life is an ineffective diversion from the true purpose of Old Age: to direct Life toward virtue and cast out spiritual despair (B.20.172). Just as the Physician of the “General Prologue” has studied a long list of Greek, Arabic, and other medical sources, “but little of the Bible” (1.438), Langland’s “phisik” transgresses in that he displaces spiritual action with medical practice.

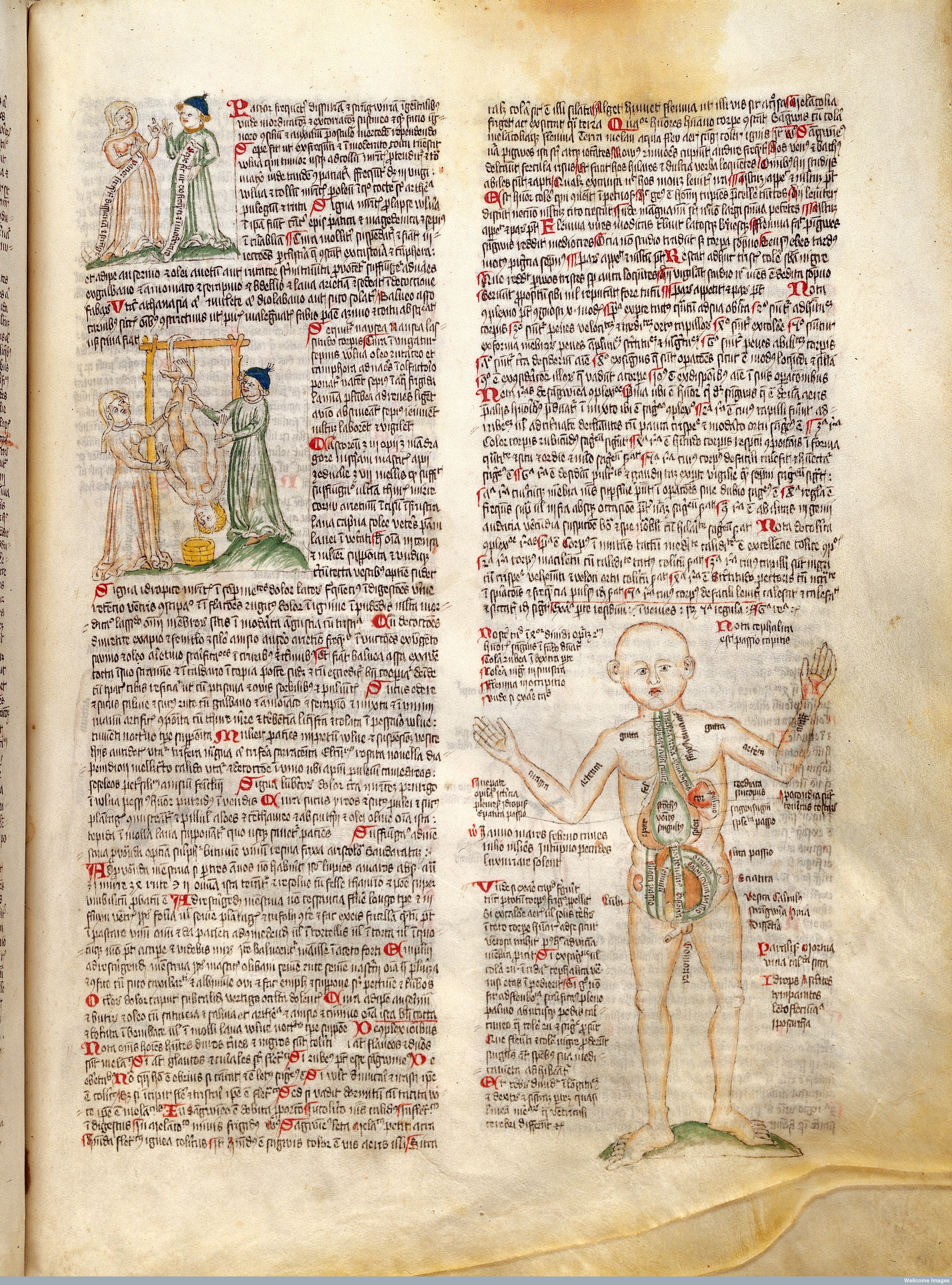

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Woman and doctor talking; text from accompanying treatise on scrolls – Woman and doctor hanging a nude woman upside down by her feet from a scaffold over a bucket for suffumigation – Disease man

Ink and Watercolour

1420? MS. 49

Wellcome Apocalypse

Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Both Chaucer and Langland portray physicians who use the cachet of their expertise to exploit their patients. One of Langland’s earliest adaptors, however, demonstrates that not everyone took such a caustic view. The maker of Piers Plowman Z, takes care to specify that medical knowledge is valuable, and that at least some of its practitioners are worth consulting. In interpolated lines not present in any other version of Piers, Hunger says:

I defame not fysyk (medicine), for the science is true,

But incompetent scoundrels that cannot read a letter

Make themselves masters men for to heal.

But they are master murderers who slay men,

And no leches (doctors) but liars, Lord amend them!

In Ecclesiastes the clerk that can read

May see it there himself and then teach another:

‘Honor the doctor,’ he says, on account of the ‘need.’ (Z.7.260-267)

In this passage, the Z maker is more concerned with the intellectual hierarchy generated by medical knowledge than he is with “fysyk” itself. He criticizes those without what he deems sufficient education, he applies the logic that the misuse of medicine can be fatal in order to encourage the exclusion of the untrained, and he adds to this sense of hierarchy by immediately asserting that “the clerk that can read” should mediate the Bible for his less educated audience. This passage indicates that understanding not just of the medical material, but also of the ethical implications underpinning it, must be mediated by a professional. The Z maker’s frustration is akin to that of many of today’s physicians when their patients diagnose themselves using pharmaceutical commercials and online forums. In the case of Piers Plowman Z, this tension is amplified by the integral nature of bodily and spiritual healing in medieval culture.

Erica Machulak

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Founder of Hikma Strategies

References and Further Reading

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Riverside Chaucer. Edited by Benson, L.D. and Robinson, F.N. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1987.

Chen, Pauline W. “Doctors and Their Online Reputation.” New York Times, March 21, 2013. https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/21/doctors-and-their-online-reputation/.

Dumas, Geneviève, and Faith Wallis. “Theory and Practice in the Trial of Jean Domrémi, 1423–1427.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 54, no. 1 (January 1, 1999): 55–87.

Fuller, Karrie. “The Craft of the ‘Z-Maker’: Reading the Z Text’s Unique Lines in Context.” Yearbook of Langland Studies 27 (2013): 15–43.

Getz, Faye. Medicine in the English Middle Ages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. “Confronting the Scribe-Poet Binary: The Z Text, Writing Office Redaction, and the Oxford Reading Circles.” In New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices Essays in Honor of Derek Pearsall, edited by Sarah Baechle, John J. Thompson, and Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, 489–513. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014.

Langland, William. Piers Plowman: The B Version: Will’s Visions of Piers Plowman, Do-Well, Do-Better and Do-Best. Edited by George Kane and E. Talbot Donaldson. London: Athlone Press, 1975.

McVaugh, Michael. Medicine before the Plague: Practitioners and Their Patients in the Crown of Aragon, 1285-1345. Cambridge History of Medicine. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Pho, Kevin, and Susan Gay. Establishing, Managing, and Protecting Your Online Reputation: A Social Media Guide for Physicians and Medical Practices. Phoenix, MD: Greenbranch Publishing, 2013.

Rawcliffe, Carole. Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England. Stroud, England: Alan Sutton Pub., 1995.

Rawcliffe, Carole. Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2013.

Rigg, A.G., and Brewer, Charlotte, eds. Piers Plowman: The Z Version. Studies and Texts 59. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1983.