Few mythological creatures have remained as present in Western cultural imagination as the fabulous and fiery phoenix. Phoenix mythology quickly became a poetic muse for classical authors from Ovid (Metamorphoses 15) to Lactantius (De ave phoenice). This mythographic and poetic tradition is later adapted in the Old English Phoenix, a poem found in the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501). For my contribution to The Chequered Board’s ongoing series on Anglo-Saxon poetry in translation, I selected to translate a section from the Exeter Book Phoenix poem (lines 1-49), which I have titled “Æþelast Lond,” and which describes the heavenly home of the mythological phoenix.

My translation of the Exeter Book Phoenix is—first and foremost—a “creative” adaption of the Old English original. As a translation, “Æþelast Lond” is an interpretive rendition of the Exeter Book poem and should not be taken as a literal translation of the Old English, but rather as an experiment with artistic translation as a means of interpreting Anglo-Saxon verse. Throughout the piece I try to remember the certain poetics specific to the Exeter Phoenix, in addition to the literary traditions of phoenix mythology and the mysterious paradise in which the phoenix bird lives.

Hæbbe ic gefrugnen þætte is feor heonan

eastdælum on æþelast londa,

firum gefræge. Nis se foldan sceat

ofer middangeard mongum gefere

folcagendra, ac he afyrred is

þurh meotudes meaht manfremmendum.

Wlitig is se wong eall, wynnum geblissad

mid þam fægrestum foldan stencum.

I have heard that hence in faroff dales

Are Eastern fabled fields,

A fay realm known yet impossible and impassible

To human folk of earthen mold,

Guarded and disguised and determined,

Purged of evil and impurity.

A place of winsome wonder, blessed with edenic bliss

And the fairest fragrance of paradise.

(“Æþelast Lond,” ll. 1-8)

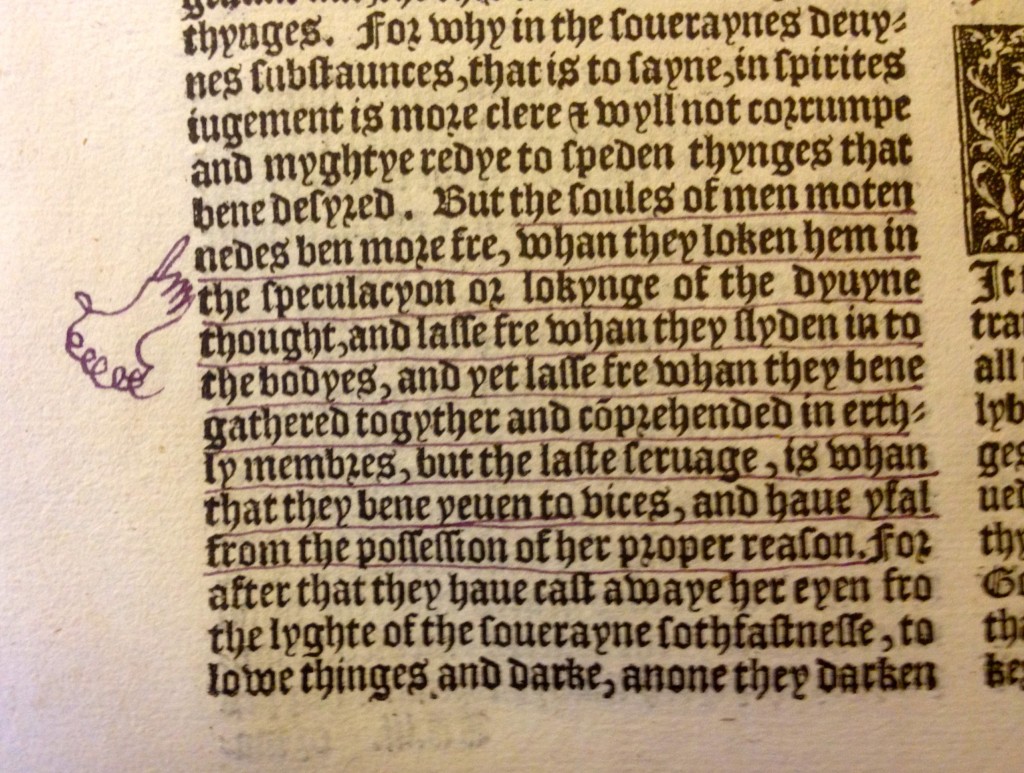

The Exeter Book Phoenix is itself a translation of Lactantius’ De ave phoenice—from Latin hexameter into Old English alliterative verse—which I have here translated into modern English free verse. Anglo-Saxon poetic and homiletic styles work in tandem throughout the Exeter Book poem, as Janie Steen and others have long noticed. It can be noted that the first line of my translation “I have heard that hence in faroff dales” (1), metrically echoes, even mimics, the Old English alliterative verse structure. While there is a somewhat contrived, mechanical quality to this line, I wanted to begin by paying metrical homage to the original poetics, before swiftly departing from any strict metrical parameters. However, despite that only this line attempts to slavishly resurrect Old English metrics, alliterative adornment remains a consistent stylistic feature throughout “Æþelast Lond”.

I attempt to resurrect the homiletic style of the Exeter Book Phoenix in my rather literal rendition of the ne…ne formulaic sections of this Old English “translation” (such as lines 15-19 and 22-25), which is in part an expansion on the nec…nec formula from Lactantius’ De ave phoenice. These formulae, Latin and Old English, are also popular in contemporaneous Old English and Anglo-Latin homilies. The cadence of this section in the original produces a masterful blend of Old English homiletic style and alliterative verse. For this reason, I felt this section deserved a more literal translation, with as much attention and adherence to metrics, style and diction as possible, in order to reproduce the rhythm and rhetorical effect produced by this simple, formulaic repetition.

Moreover, diction—for any poet or translator—is a point that merits some brief discussion. Again, I begin with a higher frequency of words etymologically derived from Old English, such as “hence” (1), “folk” (4), “mold” (4), “winsome” (7), etc. However, by the ninth line of the poem, my diction shifts toward the Latinate and ecclesiastical, and terms such as “celestial” (9), “creation” (11), revelation” 12), “angelic” (13), etc., in order to reflect the spiritual concerns and homiletic tone of the Exeter Book original poem.

The eastern wong or “plain” where the phoenix lives is heofon “heaven” in the Old English original, and thus in my translation, I focus my attention on the mystical space and mysterious home of the phoenix, central to this section of the poem. In the Exeter poem, two traditions of phoenix lore come together regarding where this mythical bird originates. The classical description of the phoenix as coming from the East (usually Egypt—at times India or Arabia) derives from Herodotus’ famous Greek account in his Histories, which lays the foundation for much of classical phoenix mythography. The Old English echoes this origin for the bird’s home: Hæbbe ic gefrugnen þætte is feor heonan/ eastdælum on æþelast londa (1-2) “I have heard that there is the best of lands far hence in the eastern parts.” The other tradition, which becomes syncretized with the classical accounts, comes from the Abrahamic tradition, and describes the phoenix as a bird of paradise.

M. R. Niehoff has noted commentaries on the Midrash and Talmud, which describe the phoenix (chol) as refusing to eat the forbidden fruit and thereafter gaining everlasting life along with the chance to remain in paradise. The paradisal quality is present also in the Old English, as the phoenix’s home is a place not of this world: wlitig is se wong eall, wynnum geblissad/ mid þam fægrestum foldan stencum. “The plain is all shimmering, blessed with joys and with the fairest smells of the earth” (7-8). As Christianity developed during the late classical and early medieval periods, phoenix mythology became assimilated into Christianity, often recast in allegorical association with Christ and his resurrection. These allegories are often coupled with the Abrahamic interpretation of the phoenix as a bird of paradise, featured prominently in the Old English Phoenix.

“Æþelast Lond” highlights Old English homiletic and poetic styles, combines Abrahamic and classical traditions of phoenix mythography, and raises questions about semantical versus literal translation. It is my hope that, rather than simply offering another slavish translation of the Old English, “Æþelast Lond” encourages others to engage their creativity when reading and translating Anglo-Saxon poetry.

Stay tuned for additional forthcoming translations from the Exeter Book Phoenix, reborn as modern English poems!

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited

Hill, John Spencer. “The Phoenix.” Religion and Literature 16.2 (1994): 61-66.

Niehoff, M. R. “The Phoenix in Rabbinic Literature” The Harvard Theological Review 89.3 (1996).]: 245-265.

Petersen, Helle Falcher. “The Phoenix: The Art of Literary Recycling” NM 101 (2000): 375–386.

Steen, Janie. Verse and Virtuosity: the adaptation of Latin rhetoric in Old English poetry. University of Toronto Press Inc.: Toronto, ON, 2008.