[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

The art of storytelling is a complex one, but most tales can be distilled into a simple theme: good versus evil. While this approach to narrative might not seem immediately problematic, it becomes much more obviously troubling when a group of systemically oppressed people is repeatedly cast in the role of the villain. The Jewish people in particular have suffered a lot at the hands of this discriminatory casting, as is achingly apparent in Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Prioresses’s Tale.” The poem, laden with an exaggerated anti-Semitism, has been difficult to reconcile for many critics. Some of Chaucer’s most devoted supporters excuse his prejudice as satire or as merely an unavoidable reflection of his historical and social context. I would argue, however, that these readings do not do enough to address the very real consequences of such anti-Semitism, spending too much time debating its origins rather than its effects. As Natalie Weber shows in her post “’The Prioress’ Tale:’ The Problem of Medieval Texts and the Alt-Right Movement,” Chaucer is speaking to people whose voices are still poisoning modern society. But his anti-Semitism may not even be the most famous in the world of media and entertainment. Another way we can consider “The Prioress’s Tale” and its impact on Western culture is by examining the problematic nature of Chaucer’s work alongside that of another figure who looms perhaps as large and faces similar accusations: Walt Disney. While many have debated whether or not Disney was sexist, racist and anti-Semitic, the lack of cultural sensitivity and the presence of moral oversimplification in his work have made indelible marks on popular culture, regardless of the personal feelings Disney had towards these groups of people.

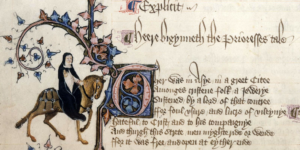

In her tale, the Prioress tells the story of a young boy who is murdered by inhabitants of a Jewish ghetto for singing the Alma redemptoris as he passes through their town. The depiction of Jewish people in this story is wholly unfavorable, to say the least, their cruelty a directive from Satan himself. The young boy, by contrast is the embodiment of religious devotion and childlike innocence. He exhibits a degree of obedience and desire to please God seldom found in seven-year-olds, no matter how pure of heart they may be. The Prioress introduces him primarily through his steadfast faith: “And eek also whereas he saugh thy’mage/Of Cristes mooder, he hadde in usage,/As hym was taught to knele adoun and seye/His Ave Marie as he goth by the weye” (Chaucer 505-508). This child devotes his whole being to the worship of Christ’s mother, kneeling whenever the occasion for it arises. Throughout the poem, the Prioress emphasizes how the child behaves as he was taught, never once suggesting that he would deviate, intentionally or otherwise, from behavior sanctioned by his mother, his teachers, or by God. He is constantly characterized as “innocent” and “litel,” making it impossible for anyone to find fault with a creature so pure. Another section following his cruel murder compares his perfection to emeralds and rubies: “This gemme of chastite, this emeraude/And eek of martirdom the ruby bright” (Chaucer 609-610). By conflating the child and his “chastite” and “martirdom” to perfect jewels, the speaker defines him and his conduct as ideal, as items that are synonymous with value.

The speaker’s representation of the Jews is as condemning as the child’s is laudatory. The Prioress’s immediate connection of them to Satan could not make their evil nature any more clear. She says, “Oure firste foo, the serpent Sathanas,/That hath in Jues herte his waspes nest” (Chaucher 558-559). As if it were not enough to accuse the Jewish people of being under the influence of Satan, the speaker had to characterize that influence as a wasp’s nest, implying not just danger, but a sort of festering corruption. They are not even distinguished by any one character, but simply exist as one uniform body of “cursed Jues.” Through the Prioress, Chaucer develops a narrative of good versus evil devoid of any character complexity on either side. Whether or not one believes that the story is evidence that Chaucer himself was anti-Semitic, he still engages with this harmful collapsing and villainizing of the Jewish community, and as Emmy Zitter argues in her essay “Anti-Semitism in Chaucer’s Prioress’s Tale,” “a satirist can be only as effective as his audience’s attitudes will allow” (278). Try as scholars might to search for reasons to read the tale as ironic, much of Chaucer’s audience would have seen such a representation of Jews as affirming of their own negative perceptions, and that fact is what makes the text dangerous, regardless of Chaucer’s intent.

Another man whose anti-Semitism has been a subject of intense debate is Walt Disney. The evidence is not totally consistent, as some cite his frequent employment of Jewish people as proof that he was not, while others claim that despite that fact Disney was deeply resentful of Jews’ success in Hollywood (Medoff). Turning to Disney’s alleged treatment of his employees is not incredibly helpful when evaluating the validity of these claims, but the stereotypes and ideals that came through in his work are much more revealing. In “Re-Reading Disney: Not Quite Snow White,” Claudine Michel describes an incident in which Disney almost let an offensive ethnic stereotype into his film:

The first version of The Three Little Pigs(1933), for example included a scene in which the Big, Bad Wolf disguised himself as a Hebrew peddler, complete with bear, long robe and thick spectacles. After leaders of the Jewish community in the US met Walt Disney to express their concern that such caricatures should not be lent legitimacy in the eyes of children at a time when anti-Semitism was rising around the world, he reluctantly changed the wolf’s disguise to that of an ordinary brush salesman. (12)

While most of the Disney films that persist in the modern consciousness stop short of egregious anti-Semitism, problematic representations of certain ethnic groups are still perpetuated by the company. In an article from the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, Rachel Shalita from the Education Department at Hamidrasha Art Academy discusses the ways in which more modern Disney films promote anti-Semitism. The article’s author, Dana Shweffi, writes, “Shalita claims Aladdin depicts Arabs in a way that is reminiscent of old anti-Semitic cartoons and caricatures. ‘The movie opens with an Arab character that looks like a caricature of a Jew with a long nose and all of the Arab characters speak English with an Arabic accent except for Aladdin and Princess Jasmine who speak with an English accent’” (Shweffi). Even though it was made in 1992, Aladdin seems to actively embrace ethnic stereotypes. Through these characterizations, the Walt Disney Company does no favors for the Arabic or Jewish people, but this simplicity of representation manifests elsewhere as well. This lack of nuance also bleeds into all Disney films’ approach to morality, a problem that is more subtle, but still has insidious effects.

In films as old as The Three Little Pigs or as new as Aladdin, Disney’s staunch conservatism continues to make its way into much of his work. As with Chaucer and his “Prioress’s Tale,” “…much of the major animated work to come out of the Disney studio, the subtleties of traditional stories are boiled down into stark moral tales of Good v Evil, the forces of light against the forces of darkness” (Michel 10). These kinds of narratives may not be as obviously as harmful as those that deal in ethnic stereotypes to make their points; they are more subtly sinister in their role in dictating the moral values of an entire culture. Debating whether or not Disney or his work was intentionally anti-Semitic is in some ways a less productive discussion than one that examines “…Disney’s work as a potentially significant factor in shaping the notions of racial and cultural hierarchy in the West and the Third World alike” (Michel 13). The simplicity of the good versus evil narrative is necessarily morally reductive and quite often places a person or group of people, sometimes Jewish people, in the position of wrongdoer. To have children consume media of this kind during such a formative period encourages them to develop a moral framework that is not unlike the one Chaucer puts forth in the “Prioress’s Tale.” Sure, the story is more compelling for its extremeness of character, but these tales also instruct one to understand humanity and morality as a dichotomy, so that when ambiguous ethical questions do arise, impressionable audiences are less equipped to deal with them.

Amanda Pilarski

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited

Medoff, Rafael. “Streep Ignites Debate: Was Walt Disney Anti-Semitic?” The American Israelite, 2014.

Michel, Claudine. “Re-Reading Disney: Not quite Snow White.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, vol. 17, no. 1, 1996, pp. 5-14, doi:10.1080/0159630960170101.

Zitter, Emmy. “Anti-Semitism in Chaucer’s Prioress’s Tale.” The Chaucer Review, vol. 25, no. 4, 1991, pp. 277-84.

Shweffi, Dana. “Do Disney Movies Promote Anti-Semitism and Racism?” Haaretz, Haaretz Daily Newspaper Ltd, 16 Aug. 2009, www.haaretz.com/1.5092056.