My newly formed theater company, FaeGuild Wonders, having successfully organized two RenFaires last year, Enchanted Orchard Renaissance Faire (annual) and Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire (year one), was ready to pursue one of my bucket-list items, an immersive and interactive full scale theatrical production of Beowulf. We pitched this idea for a winter festival centered on medieval literature to our partnering venue, Red Apple Farm, and the NorthFolk NightMarket was born. This event, to take place February 22-23, 2025 (from 3-9 PM EST), while expanded and redesigned, is in a sense a development of an older project, Grendelkin, which I began to conceive during my graduate studies as the University Notre Dame. With support from the Medieval Institute, Grendelkin debuted at Washington Hall in 2017, bringing together scholars, artists, dancers, musicians and storytellers to create an avant-garde interpretation of Beowulf centered on issues of monstrosity and heroism in the poem.

So far as creative director, I have only done fantasy theatrical medievalism at this scale: the “Wyndonshire Wedding” at Wyndonshire and “Seeds of Wonder” at Enchanted Orchard. And don’t get me wrong, I’ll probably mostly (or always) do fantasy in my theatrical medievalism. But in the NorthFolk NightMarket, I get the opportunity to explore some of my favorite works of medieval literature in a playful, interactive and public facing way. In many ways it’s anachronistic, and as my intention is to follow certain works of literature, the fantastic is imbued into the story and the spirit of the event.

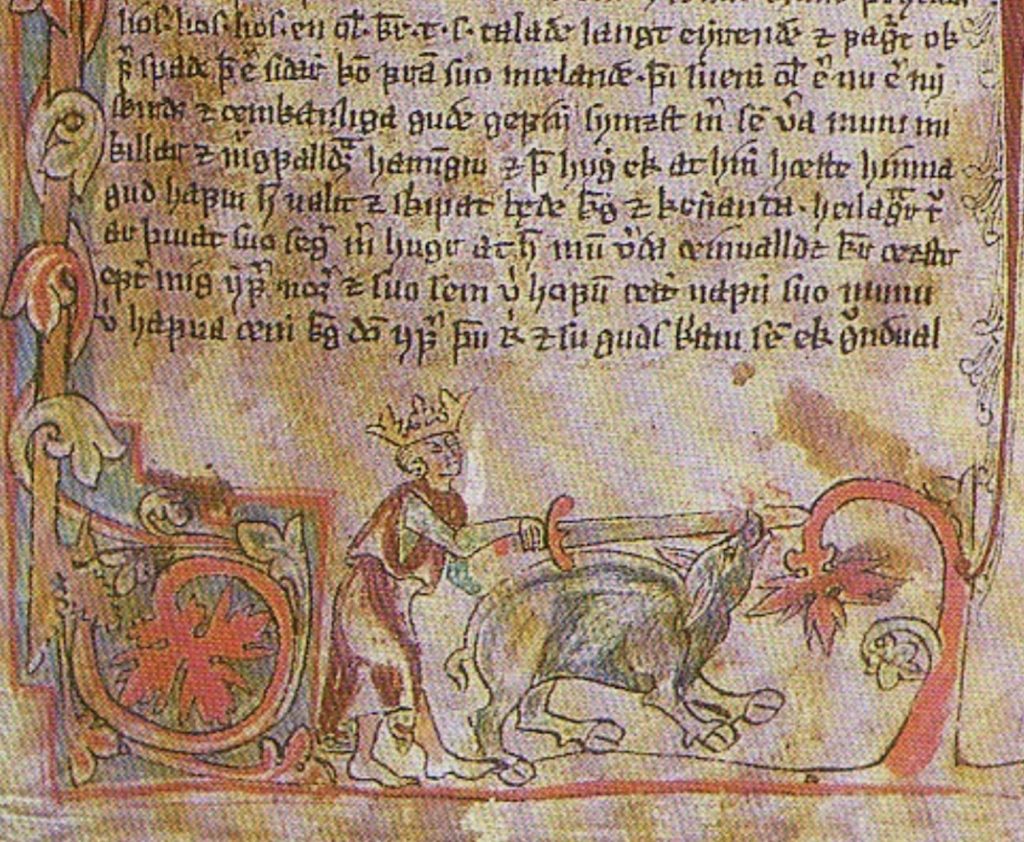

My approach to authentic medievalism expressed in public theatrical events is not to focus on historical accuracy but to bring works of medieval literature to life for modern audiences and ways that are engaging, relevant and exciting. I also feel that the performances and music which is incorporated into the event, add layers to the NorthFolk NightMarket shows. For example, there are two songs included in the Beowulf show, one sung by Frank Walker, and another by Melegie (Melanie Long) that come from my translation or paraphrase of sections of farewell. In particular, the “Lay of Sigmund” is a versification of my translation, while Hildeburh’s song is an abbreviated redaction of her experience versified and accompanied by harp.

The main plot of the NightMarket’s theatrical production is the story of Beowulf, and a dream of mine realized. Beowulf is of course the subject of my dissertation, as well as much of my published scholarship, which centers on the Old English poem and the intersection between Anglo-Latin learning and Germanic lore, as well as tensions between Christian and pre-Christian ethos and worldviews in Beowulf. I composed an original script for the poem, some of which comes directly from my translation of Beowulf, and which imbues some scholarship as well as my own critical reading in this adaptation of the story. I also strove to elicit the humor I perceive in Beowulf, though irony in the poem is a topic of much scholarly debate and discussion. The cast includes the protagonists, Beowulf (Dave Fournier), Hroþgar (Gary Joiner), Wealhþeow (Leanne Blake) and Wiglaf (Mitchell Long), as well as supporting roles and characters from stories within the story, such as Hunferth (Dan Towle), Wulfgar (Devon Barker), Hondscio (Sezo Veniche), Æschere (Bryan Fallens), Hroþulf (Jack Praino), Hildeburh (Melegie: Melanie Long), Modthryth (Sylvia Sandridge), Hygd (Elizabeth Lassy-Glazier) and the Beowulf-burglar (Richard Goulette).

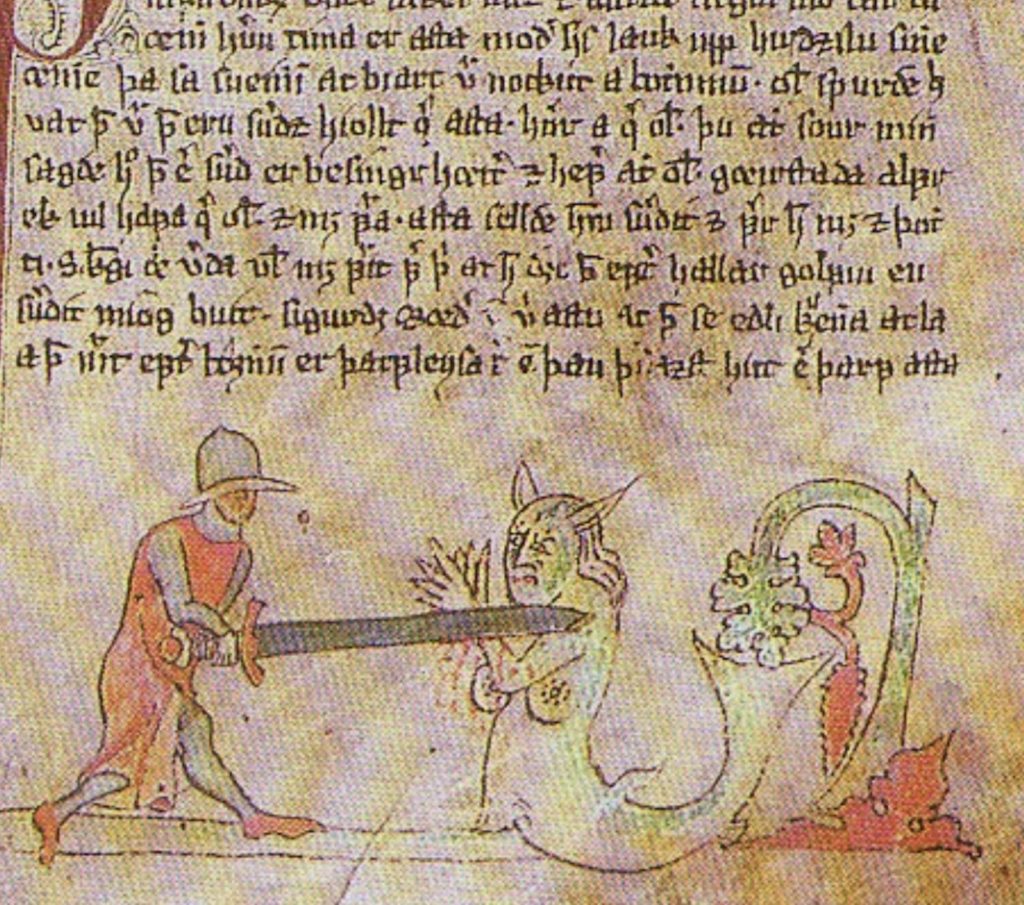

The story starts with Hroþgar’s boast and the terror of Grendel, until Beowulf arrives to slay his Danish demon in Act I. Ironically, and unwittingly, the hero performs a handshake exorcism upon the monster, inspiring Grendel to flee and rip off his own arm in his terrified retreat. Grendel’s mother is in Act II, and her story is centered on the horror of maternal experience in the heroic world of Beowulf and the sorrow of mothers within poem, in particular, how Wealhþeow, Hygd, Hildeburh and Grendel‘s mother all lose their sons (or will soon lose their son) throughout the narrative, and this dread and trauma frames the act as a prominent theme in the story. By the time we get to Act III, featuring the Beowulf-burglar’s theft of the treasure-cup and Beowulf’s wrath in the dragon battle, the focus is on hoarding and the plunder economy. In this way, I emphasize my psychomachic reading of Beowulf, especially his encounters with the monsters, into a performance that highlights the ironic comedy that underpins my reading.

The NorthFolk NightMarket is about storytelling and wintering—entertainment while holding up in a hall or homestead in the north in order to survive the harsh, cold winter season. As an event designed to become an annual tradition, the plan is to center a different medieval literature every two years, and so we selected a story frame that would be consistent each year: witches from different literary and folkloric contexts, who are together plotting an Imbolc Sabbath while they observe, interact, and tell whatever medieval tale is being told that year.

The Witches’ Sabbath includes well-known magic women from myth and legend, including Baba Yaga (Jessa Funa), Gryla (Katharine Taylor), Befana (Kellie Carter), Grimhild (Davyn Walsh), Morrigan (Chelsea Patriss), Medea (Lauren Robinson) and the Norns (Siobhan Doherty, Chrissy Brady & Kate Saab). The story frame is the organization of the Sabbath, and especially the tensions between these witches, who wish to invoke spring, and the Snow Queen (Jen Knight) and her frost fairy court, who wish to preserve the winter. In addition to our cast of character actor witches, a local performance group is also integrated into the theatrical show, the Mt. Wichusett Witches, and they have organized two dances for the Sabbath at the end of each day, which is Act IV, the final scripted act of the event.

Accompanying Gryla are the Yule lads, from Icelandic folklore and cultural tradition, who promise to bring a bit humor to the event. This group has a number of immersive skits right in Red Apple Farm’s store, and a high school student and my assistant playwright for the event, Nikolaus Chagnon-Brauer, has taken lead on scripting these scenes. One of the joys of organizing this event has been collaborating with Nikolaus on this aspect of the winter festival, as doing so has allowed FaeGuild to carry out part of its mission to engage young people creatively and to build a team that is multigenerational.

In addition to wandering witches, fairies and Yule lads, there will be marauding trolls, thanks to the puppetry of Skeleton Crew Theater another local partnering theatre company, as well as the Celtic goddess-made-saint, Brigid (Micayla Sullivan), the German demon Krampus (Sasha Khetarpal-Vasser), and Old Norse gods and goddess, including Odin (Richard Fahey), Freya (Sara Hulsberg), Tyr (Brawn Beserker), Thor (Andrew Hamel), Sif (Gabrielle Emond ), Loki (Tom Fahey), Bjorn (Lee Mumford), Weland (Christopher Lassy-Glazier) and Hel (Kerri Plouffe), many played by members of the live theater group the Green Sash.

Our Art Team for this event, led by Art Director Rajuli Fahey, and including Sylvia Sandridge (Costume Coordinator), Micayla Sullivan (Stagecraft Coordinator), Dave Fournier (Groundskeeper), and Gary Joiner, has endeavored to construct a world derived primarily from Beowulf and folklore. There will be the mead hall of Heorot, a haunted barrow, a path of exile, a monster mere, snow queen court and a witches’ den, in addition to many other set pieces based on myths and legends surrounding characters featured at the event.

The NorthFolk NightMarket, as with Enchanted Orchard Renaissance Faire and the first year of Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire, has been a community effort. We are blessed to have so many exceptional and creative organizers as part of the FaeGuild Wonders team. One example is our Music Director, Leanne Blake, and the FaeGuild singers, who have put organized an incredible show that weaves together all the threads of the NightMarket, and which is sure to be a highlight of the events.

Additionally, for this event, we have added a new component, organized by our Immersive Director, Michael Barbosa-MacLean and the FaeGuild players, who will be on the streets of the NightMarket to bring patrons directly into the world of the faire. Other event organizers include our Jessa Funa (Community Coordinator), Amy Boscho (Fairy Court Coordinator), Tom Fahey (Sound Manager), Tal Good (Administrative Assistant) and Siobhan Doherty (Administrative Assistant). Without such an incredible team of creative partners, this inaugural event would not be possible.

The NorthFolk NightMarket features a market of artisan vendors, and an array of other performers including the Harlot Queens, Shank Painters, Winds of Alluria, Dead Gods Are the New Gods, the Iconic Daring Divas, the Phoenix Swords, the Warlock Wondershow, fire spinners and more. Additionally, there will be several historical demonstrations, including two historical combat groups, Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) and Bayt Al-Asad: Middle Eastern Combat Arts (House of the Lion), which will educate festival goers on different historical sword-fighting traditions. There will also be specialty ciders, historical cooking and blacksmith demonstrations as part of the event.

In carrying on our tradition from previous faires, our focus is on community building and sustaining the arts, and we are honored to have been supported by so many community sponsors. In particular, we would like to thank Atlantic Tent Rental (for the discount and donated tent rentals), Market Basket (for use of their parking lot), the Armenian Church of Haverhill (for the beautiful wood donated to build the Hrothgar’s meadhall, benches and throne), Central Mass Tree Inc. (for providing firewood to keep everyone warm in the cold night), Eastern Propane (for providing gas for heat lamps needed in vendor tents), Killay Timber Company (for the wood for signage), Belletetes Lumber (for wood to build the set) and Magnolia Studio (for providing the cozy rehearsal space).

Organizing public medievalism events like this has been a dream come true. And I can say with certainty that the theatrical production of Beowulf at the NorthFolk NightMarket will be unlike any theatrical adaptation of the poem, and far from the usual treatments of the poem in popular culture, as it is derived from my own criticism and scholarship (and including others’ scholarship that has influenced mine as well). As such, the NorthFolk NightMarket presents the story of Beowulf as an ironic critique of heroism rather that a glorification of a warrior ethos (especially the desire for fame, vengeance and wealth) those very aspirations that so frequently continue haunt our modern world.

Further Reading

“The Wyndonshire Wedding: Theatrical and Community Medievalism.‘” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (September 4, 2024).

“Crafting a New Kind of Renaissance Faire: Theatrical Medievalism and the Aesthetic of Wonder.‘” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (August 14, 2024).

Fahey, Richard. “Grendel’s Shapeshifting: From Shadow Monster to Human Warrior.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (October 27, 2021).

—. “Enigmatic Design & Psychomachic Monstrosity in Beowulf.” Dissertation: University of Notre Dame (2019).

—. “The Lay of Sigemund.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (March 22, 2019).

Griffith, Mark. “Some Difficulties in Beowulf, Lines 874-902: Sigemund Reconsidered.” Anglo-Saxon England 24 (1995): 11-41.

Gwara, Scott. Heroic Identity in the World of Beowulf. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

O’Brien O’Keeffe, Katherine. “Beowulf, Lines 702b-836: Transformations and the Limits of the Human.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 23.4 (1981): 484-94.

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Schulman, Jana K. “Monstrous Introductions: Ellengæst and Aglæcwif.” In Beowulf at Kalamazoo: Essays on Translation and Performance, 69-92. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2012.

Vinsonhaler, N. Chris. “The HearmscaÞa and the Handshake: Desire and Disruption in the Grendel Episode.” Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 47 (2016): 1-36.