This entry picks up from my last, in which I reflected on the potential of mise-en-page to communicate something about the genre or tenor of a text, and on the oddity of King Horn in Harley MS 2253 being written uniquely in aabb rhyming long lines. Below are my thoughts on what the poem gains from such mise-en-page:

While it could never be said that King Horn is a strictly alliterative poem, it undeniably exhibits a conscious amount of alliteration throughout, frequently to great effect,[1] putting it in good company with the majority of the English lyrics in the Harley manuscript which characteristically alliterate to some degree, some very strongly. In fact Henry West, in an old study, bases his entire theory of a two-stress scansion for Horn on the poem’s alliterative qualities.[2] Because of its particularly English reliance on heavy stresses, reminiscent of Horn’s Anglo-Saxon predecessors, one can effectively hear even the slight alliteration of the short lines that form the poem’s couplets. Horn is usually considered the earliest Middle English romance we have, and it is likely that the original composer of the poem, working from their probable Anglo-Norman source material, was an early adapter of the new genre into English, experimenting with a combination of the inherited rhymes of French romance and with the alliterative line of Anglo-Saxon and early Middle English poetry.[3] Moreover, in its Harley context, with its somewhat sporadic alliterative techniques and rhythms with simple rhymes, the poem falls nicely alongside the lyrics attempting a marriage between rhyme and alliteration in precisely the same way, all the while clearly drawing from a continental lyrical tradition as well.[4]

If we take into account the preceding, and thus if we see the line as our scribe did or–rather–hear it as its audience would have, it bears some small resemblance to the traditional four-stress line. The following “four” lines from Horn, arranged as they are in Harley, demonstrate this tendency at its strongest:

swerd hy gonne gripe // & to gedere smyte

hy smyten vnder shelde // þat hy somme yfelde

(ll. 55-58) [5]

In these lines we have three alliterative staves over a traditional four stress line. Detecting such examples suggests a conception of Horn in which the features of alliteration and the long line layout mutually affirm the poem’s indebtedness to and are evocative of an earlier English tradition. Of course, if we read Horn in the Harley manuscript, we can see that the scribe at least felt that the poem was suited to the long line and wrote it in that way, seeing Horn in much the same light that we now see Laȝamon’s Brut, perhaps its closest true poetic precursor. Let us take a few exemplary lines from the Brut:

And seoððen, vmbe stunde, // he ferde to Lunden;

he wes þere an Æstre // mid aðele his uolke;

bliðe wes þe Lundenes tun // for Vthere Pendragun.

He sende his sonde // ȝeond al his kinelonde;

he bæd þa eorles, // he bæd þa cheorles,

he bæd þa bischopes, // þa boc-ilærede men

þat heo comen to Lunden // to Vðer þan kingen,

into Lundenes tun // to Vðer Pendragun.

(ll. 9229-36)[6]

So we have in the above example, in eight long lines, six lines with internal rhyme (or near-rhyme), and six with alliteration of an irregular sort. The erratic rhyme and alliteration here is somewhat surprising, given that Laȝamon is often thought to be writing in a way intended to be evocative of his Anglo-Saxon forebears, but Elizabeth Salter suggests such surprise at Laȝamon’s prosody ignores the historic context of the poet, a context which “allowed for the coming-together of diverse but essentially traceable literary influences: French, Anglo-Norman, English and Latin.”[7] In some ways, then, editors of Laȝamon overemphasize the poet’s dedication to old forms in their choice to lay Laȝamon out in long line—no extant manuscript of poem does so. Instead, in manuscripts, the poem is written in block columns with verses separated by virgules.

The choice to print the text in long lines merely emphasizes the shakily consistent alliterative qualities of the poem over its similarly consistent leonine rhyming. One could print the poem as successfully in rhyming couplets. Recognizing that the layout of a poem’s lines can alter on which literary tradition emphasis falls, I see modern editors of Horn and Laȝamon struggling with the very same choices as medieval scribes regarding mise-en-page. The problem is, with the emphasis on silent reading today, what we see on the page crystalizes a poem’s form in a way which the medieval listener would not have experienced.

W.R.J. Barron and S.C. Weinberg describe Laȝamon’s prosody, his “constant variation,” thusly:

For [Laȝamon] alliteration seems no longer an essential organizational principle; in nearly one line in three it is entirely absent. Yet it is too frequent to be merely ornamental and, in some passages, so regularly associated with stress as to echo its classical usage. Similarly, though the majority of half-lines are of two stresses only, some have three or even four; others half-lines are rhythmically so uncertain as to leave the determination of the stress pattern to the individual reader. (xlix-l)

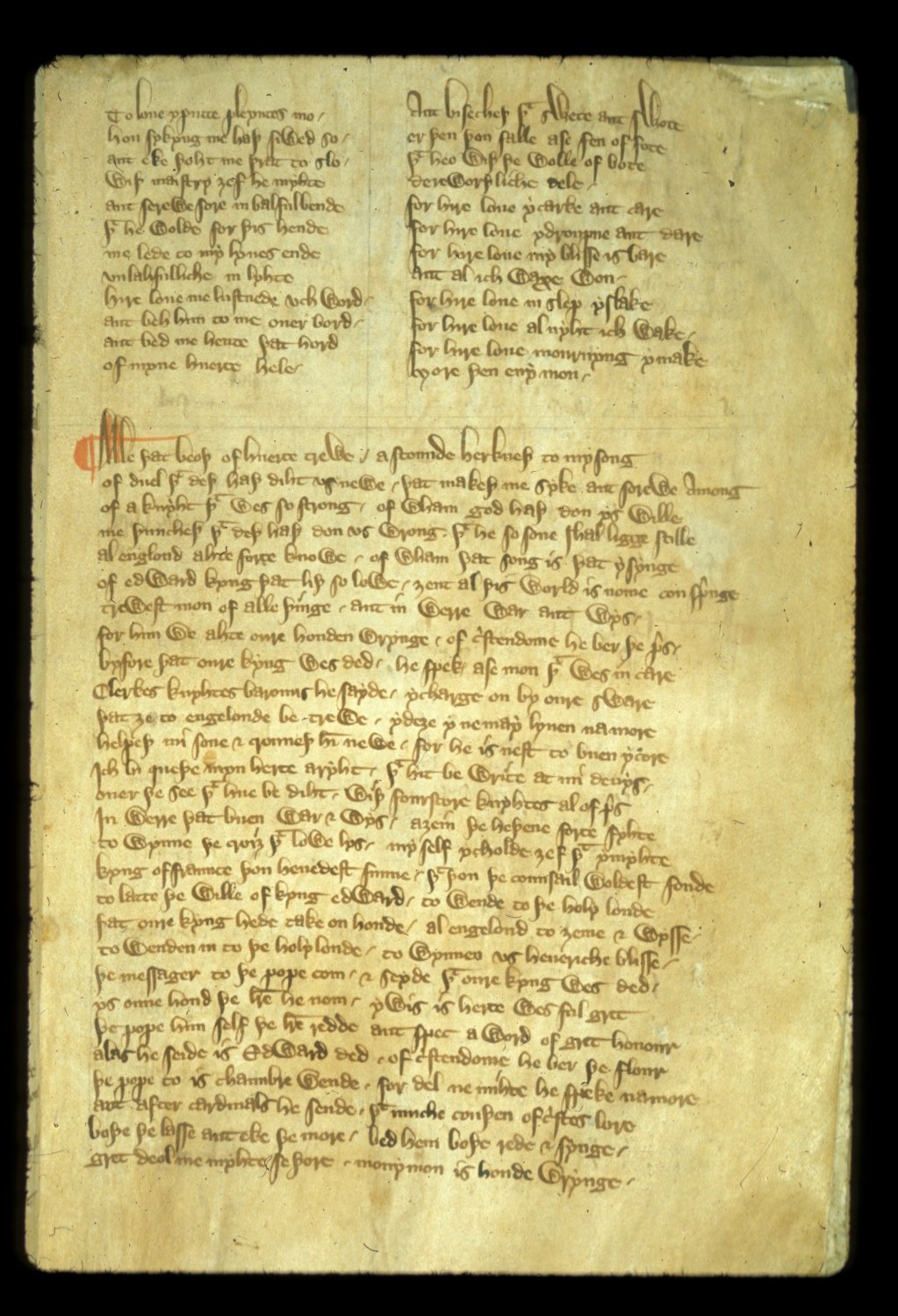

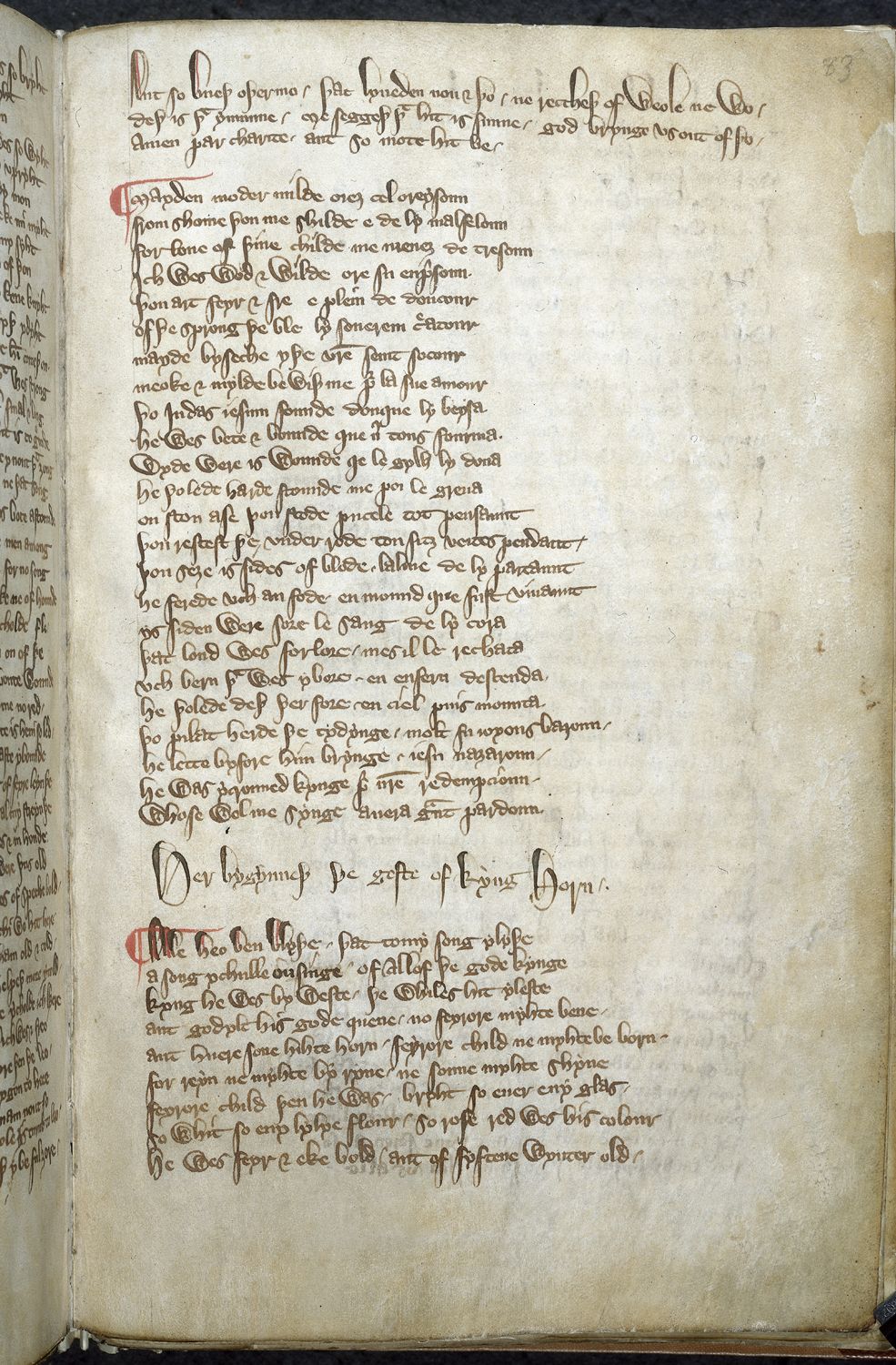

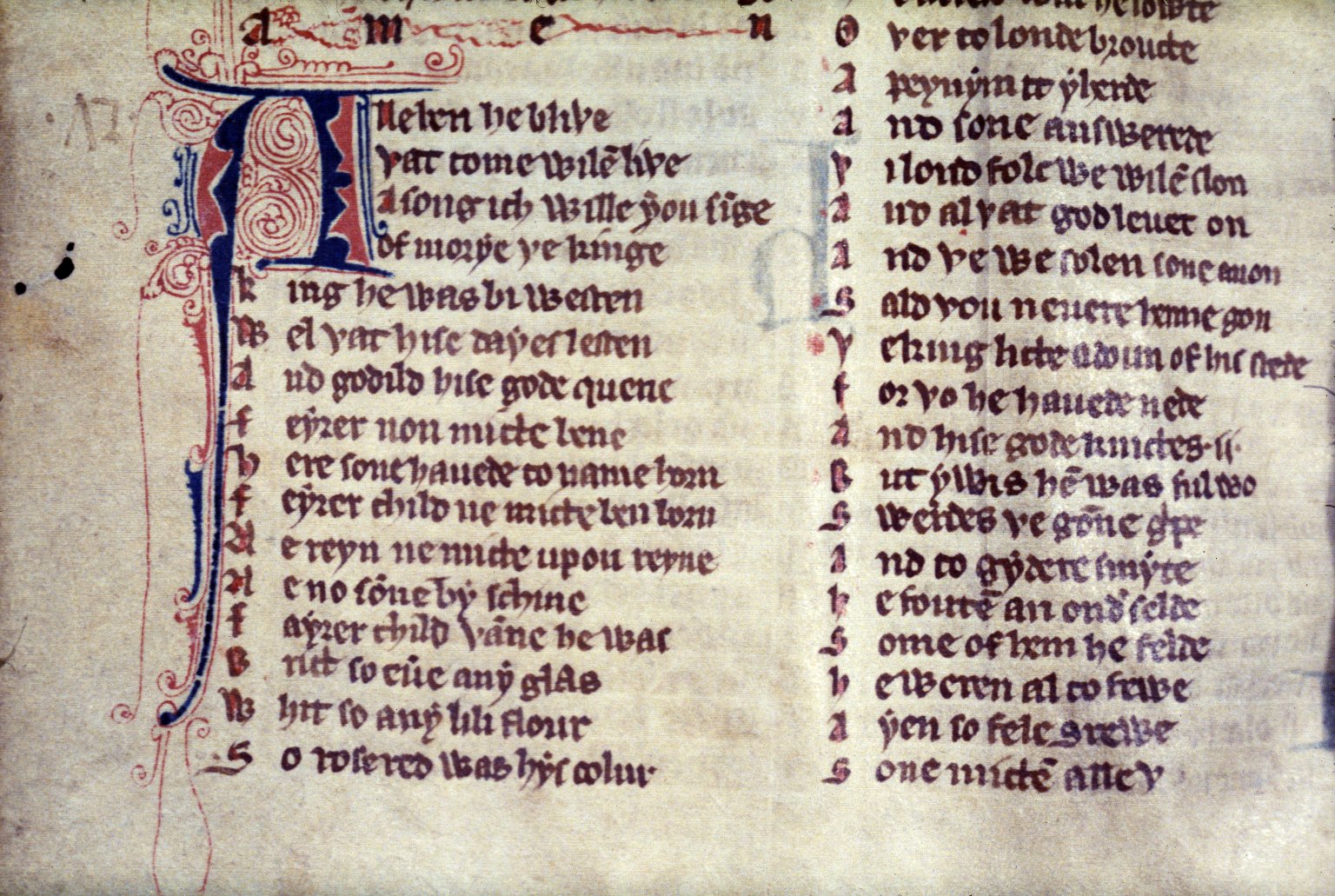

Barron and Weinberg, not to mention Salter, might as well be describing Horn. In its sporadic, yet persistent alliteration, its constant, though clumsily regulated two-stress line, its semi-competent rhyme scheme, and its obvious indebtedness to multilingual literary traditions, Horn is the near twin to the Brut.[8] And yet, modern editors are not alone in uncertainty regarding Horn’s metrical status. Our medieval compilers too must have struggled with how to present Horn in a manuscript, as the other two manuscripts of the poem suggest. While Oxford Bodleian MS Laud, Misc. 108 maintains a regular, if cramped, short-line throughout, Cambridge MS Gg. 4.27.2 tells a different story, with two short lines frequently written as one, with no discernible agenda—the long lines emphasize nothing special in alliteration, rhythm, or rhyme—as though copied by a scribe who could not make up his mind, or who habitually and unconsciously heard the long line in his copying only to be set straight by his short-line exemplar upon glancing back. Horn in Harley 2253 (see figure), however, is written in long line, a choice that consciously sets Horn back into an English tradition all the more emphasized by its manuscript’s co-inhabitants, many of which were consistently written in alliterative long lines with rhymes at their caesura.[9]

Additionally, there is little reason to suppose that, as Elizabeth Solopova suggests, “the reason for [the use of the long line in Horn] could have been the scribe’s wish to save space through an economic layout of a long text.”[10] As I observed in my last post, the Harley scribe used a variety of ordinatio in his manuscript, writing pages of one, two, or three columns, and at times his choices in mise-en-page were guided by artistic rationale.[11] If the Harley scribe were really intent on saving space, writing in short line would have been ideal,[12] as it would have allowed for the writing of a three-column page, which was in fact precisely what the scribe did only a page earlier (fol. 82) when copying “Maximian.” Furthermore, while Ker supposes that Horn may have been copied this way because of the scribe’s exemplar,[13] the scrupulous care with which the Harley scribe is often thought to have set out his texts suggests a motive behind the rare exception.[14] The inclusion of Horn in long line form allows the poem to inhabit the manuscript in a way that is less intrusive to its surrounding texts and more meaningful in establishing Horn as a particularly English brand of literature drawn from a pool of influence as varied as that from which Salter would have the Brut drawn.

Despite the suggestiveness of its mise-en-page in Harley, Horn is invariably edited as a short-line poem in all of its editions excepting its 1901 EETS publication,[16] even Hall’s parallel one, an editorial decision that unavoidably pushes aside associations with certain types or genres of poetry and foregrounds the poem’s associations with other genres. The end result of editions like Hall’s[17] is to create the illusion of stasis for a poem that can be looked to as a fascinating example of the transitional nature of the developing English poetic tradition, an instability highlighted by the poem’s gestures to orality and older traditions. By the time the Harley scribe copied Horn (1331-41), after all, the poem was quite old.[18] Perhaps our scribe signified, in his mise-en-page, that he saw in Horn a poem of a more historical, ancient, and epic character than those of the romance boom being copied contemporaneously in volumes like the Auchinleck manuscript, coming out of the flourishing book industry in London.

Andrew Klein

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Notes:

[1] Henry S. West, The Versification of King Horn: A Dissertation (Baltimore: J.H. Furst Company, 1907), 33, 36.

[2] West’s theory, in turn, finds much of its impetus in Theodor Wissmann’s 1881 critical edition of Horn. Wissmann uses the Cambridge MS as his base text, using alliteration and metre to restore an original reading of Horn. See Theodor Wissman, ed., Das Lied von King Horn (Strassburg: K.J. Trübner, 1881) and for introductory material see Theodor Wissman, Untersuchungen zur mittelenglischen sprach- und litteraturgeschichte (Strassburg: K.J. Trübner, 1876

[3] Barron, Romance, 67.

[4] A fine example of this is the lyric traditionally called “The Lover’s Complaint,” in which the lyricist combines English alliterative technique and tail-rhyme form with the love-longing of French trouvères like Gace Brulé:

Wiþ longyng y am lad,

on molde y waxe mad,

a maide marreþ me;

y grede, y grone, vnglad,

for selden y am sad

þat semly forte se. (1-6)

Many examples of such blending exist in Harley. Poems frequently play with English forms while relying on the French tradition for themes and motifs.

[5] While Cambridge MS Gg. 4.27 (2) is usually the preferred text for editors of King Horn, I have opted to use the text found in Harley 2253 for obvious reasons. All line references, therefore, are to the old text edited by Joseph Hall: King Horn (Oxford: Clarendon P), 1901, a parallel edition of all three versions of King Horn. I have here arranged four lines from Hall as two, adding the caesural markers. The 1901 EETS parallel text edition of Horn does arrange its Harley text in long line, but Hall’s is universally preferred as the more accurate text.

[6] Layamon’s Arthur: the Arthurian section of Layamon’s Brut, ed. W.R.J. Barron and S.C. Weinberg (Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001).

[7] Elizabeth Salter, English and International: Studies in the Literature, Art, and Patronage of Medieval England, ed. Derek Pearsall and Nicolette Zeeman (New York: Cambridge UP, 1988), 61. We might recall as well the macaronic character of the Harley MS as a whole, which suggests our scribe was drawing from a similarly diverse cultural background as Laȝamon.

[8] Though it is not usually remarked upon today, the earliest editors and scholars of Horn often drew attention to a developmental relationship between the Brut and Horn. See, for instance, George H. McKnight, King Horn, Floriȝ and Blauncheflur, The Assumption of our Lady (New York: Oxford UP, 1901), xx-xxii; see also Hall, King Horn, xlv-xlvi.

[9] Elizabeth Solopova, “Layout, Punctuation, and Stanza Patterns in the English Verse,” in Studies in the Harley Manuscript: The Scribes, Contents, and Social Contexts of British Library MS Harley 2253, ed. Susanna Fein (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000), 377-89. Solopova asserts that long lines in Harley “never have leonine rhyme” (378), but this is only because she refuses to grant that Horn’s long line counts as such.

[10] Ibid., 387. This is an echo of Ritson’s very early suggestion: “The present poem, for the salvation of parchement, is writen with two lines in one” (264). Joseph Ritson, ed., Ancient Engleish Metrical Romanceës, vol. 3 (London: W. Bulmer and Co., 1802).

[11] A well-known example can be found on fol. 128r, where the Harley scribe places two poems, “The Way of Woman’s Love” and “The Way of Christ’s Love,” in clear juxtaposition. See Fein, “A Saint ‘Geynest under Gore,’” 351; Michael P. Kuczynski, “An ‘Electric Stream’”: The Religious Contents,” in Studies in the Harley Manuscript: The Scribes, Contents, and Social Contexts of British Library MS Harley 2253, ed. Susanna Fein (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000), 154-55.

[12] In reference to Horn’s spacing, Rosamund Allen notes, “Usually the scribe writes short lines in two columns.” See Rosamund Allen, ed., King Horn: An Edition Based on Cambridge University Library MS Gg.4.27 (2) (New York: Garland, 1984), 13. For an example of how closely our scribe paid attention to arrangement of texts in Harley, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, “Major Middle English Poets and Manuscript Studies, 1300–1450,” in Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2012), 50-54. Kerby-Fulton observes that the apparent cramming in of two poems next to one another, “In the Ecclesiastical Court” and “The Labourers in the Vineyard” over three pages in fact sets the poems in a juxtaposition that allows the latter poem to comment upon the first.

[13] N.P. Ker, Facsimile of British Museum MS. Harley 2253 (New York: Oxford UP, 1965), xvii; Solopova, “Layout, Punctuation, and Stanza Patterns,” 378, also draws attention to scribe’s “highly conscious approach to [the manuscripts] layout and punctuation.”

[14] Ibid., xviii.

[15] Stemmler, “Miscellany or Anthology?,” 121.

[16] This parallel EETS edition, “now re-edited from the manuscripts” (iii) by George H. McKnight, displays all three manuscript transcriptions on a page, with the Harley edition in long-line form. Unfortunately, Hall’s edition was published that same year and, having been deemed the superior parallel text, quickly overshadowed McKnight’s. Hall’s parallel text regularized Harley with the other two manuscripts, formatting it in short lines.

[17] By this I mean parallel editions especially, but all editions of Horn (of which there are eleven, and many more selections for anthologies) other than the 1901 EETS print Horn in short lines, a tradition inaugurated by Ritson in the earliest edition of Horn. Ritson printed Horn exclusively from the Harley manuscript in 1802, and, while he adopted the title from that manuscript (“The Geste of Kyng Horn”), he did not follow the lineation.

[18] The poem has been dated between 1225-75, though the story itself was told in Anglo-Norman even earlier (late twelfth century).