Growing up, I always loved wizards. All the most epic stories seemed to have them: mysterious wanderers dispensing arcane wisdom and providing just the right information at just the right time to just the right person. Wizards—in particular white male wizards—enjoy a distinct privilege in contemporary Fantasy literature. They are part of a larger trend identified by Helen Young as “habits of whiteness” within the genre. Wizards are often presented as mythic, almost godlike, figures who wield cosmic power and inevitably play a pivotal role in the narrative even if only from the periphery.

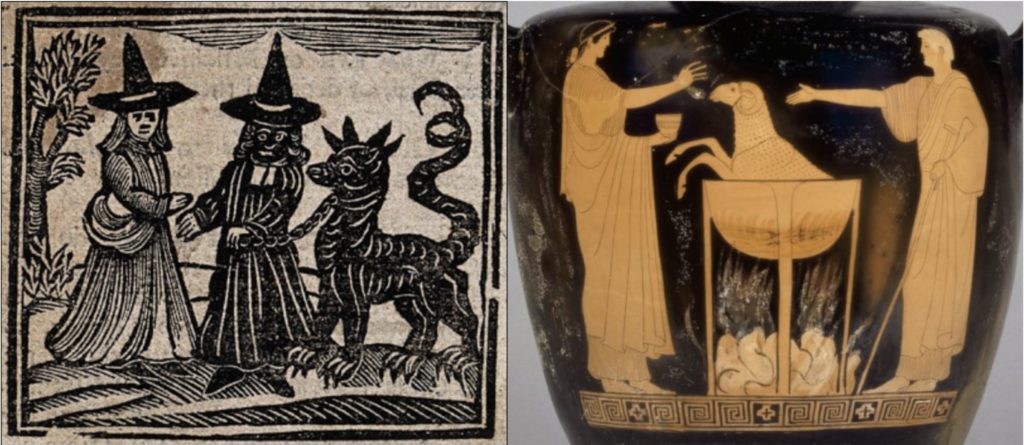

Witches, on the other hand, get the short end of the magic wand. From early medieval characterizations of Odin and Merlin to modern Fantasy figures such as Gandalf and Dumbledore, wizened male magic-users are repeatedly glorified, often leaving the more pejorative treatments for characterizations of magical women, especially witches. This wizard male privilege reinforces an ancient tradition of misogyny that likewise reaches back to the classical Greco-Roman myths of Medea and medieval tales of Morgan Le Fay, and which extends to include modern antagonists such as the Land of Oz’s infamous Wicked Witch of the West and Narnia’s White Witch, Jadis. This intersectional blog continues our recent series on magic which has recently explored issues of plague-related magical thinking, late medieval necromancy and sexist witch-stereotypes.

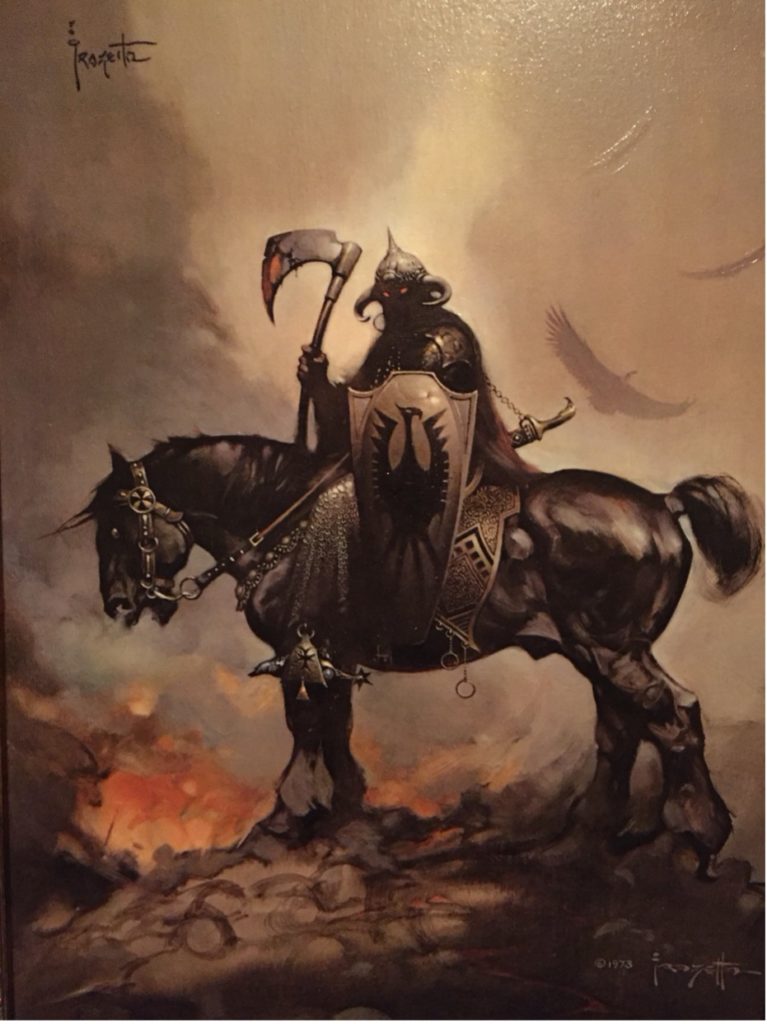

When you think of a wizard, what comes to mind? Probably some grandfatherly magician, a devout guardian of arcane knowledge and power—incorruptible and undaunted—who will face any foe and sacrifice everything for the greater good. These brilliant men are often benevolent and trustworthy advisors, stewarding from their ivory towers and steering the destinies of younger heroes. Someone like this:

This image of Gandalf from Peter Jackson’s film adaptions of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit highlights the way in which wizards are visually represented: wizened, powerful and good. This positive treatment of wisemen can be trace in the Abrahamic tradition to figures such as Moses, with his staff, curses and divine knowledge, to the three Magi—zoroastrian priests from Persia—who come to visit Christ and recognize his divinity by astrology. In the medieval tradition, King Arthur’s trusty magician Merlin is credited for building Stonehenge in Geoffrey of Monmouth fanciful Historia regum Britanniae helping to cement Merlin thereafter as an almost archetypal wizard throughout Europe. The Old Norse-Icelandic god of war and occult knowledge, Odin, likewise provides a similar image of a wise man who knows the secret runes and can therefore harness its power and magic. Even in sagas recorded centuries after Christianization, Odin is often still portrayed as generally wise and powerful.

The images of the noble wizard as a knowledgeable magician is later carried forward and adapted from characters such as the early modern Prospero in William Shakespeare’s The Tempest to iconic wizards from contemporary Fantasy literature such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s Gandalf and J.K. Rowling’s Albus Dumbledore. Wizards are principally characterized as knowledge-keepers and their power comes from their supreme intellect and years of devoted study—especially their command over magic words and occult language—emphasizing arcane wisdom and magical literacy above all. They are mentors. They are sages. Sometime they are prophets or even saviors (from Mallory’s Merlin saving an infant King Arthur to Rawling’s Dumbledore saving an infant Harry Potter).

Throughout literary history, wizards are most often of the alchemist and astronomer sort. Of course, there are also the characteristically evil sorcerers (who often take the title of “dark lord”), which include Fantasy archvillains—such as Tolkien’s Sauron or Rawling’s Voldemort. The evil sorcerer trope also encompasses complicated, conflicted or converted wizards, such as Saruman in the Lord of the Rings and Severus Snape in Harry Potter, in addition to lesser known mages such Ged from Earthsea and Raistlin Majere from Dragonlance. Most modern examples of evil sorcerers and “dark lords” are monsterized or racialized (often both), and depicted as inhuman in the fashion of a witch.

The evil sorcerer caricature likewise overlaps with a medieval magical tradition known as necromancy, which often involves imitation and perversion of the Christian mass and church ritual, with the goal of summoning and controlling demons. For this reason, Richard Kieckhefer describes this form a of magic as “demonic” but it is no less learned than other arcane and magical arts, and probably for this reason, necromancers are likewise more often gendered male. Indeed, Gandalf’s mysterious archnemesis in the Hobbit is ambiguously referred to as simply “the Necromancer” who comes from the east and requires a team of elves and wizards to handle.

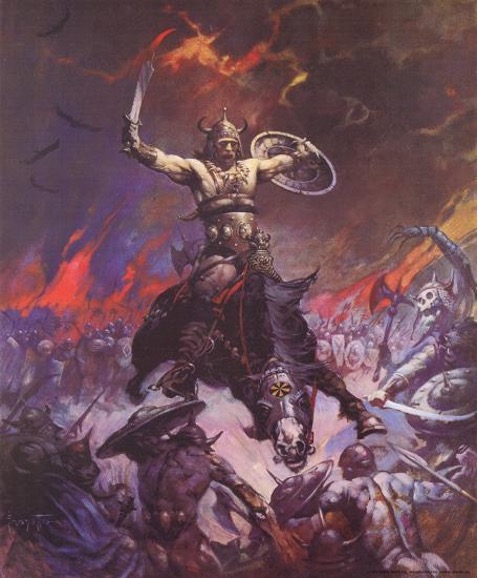

Now, when you think of a witch, what comes to mind? Probably a withered, old hag—a wicked crone—a gnarled and twisted monster. These terrifying women will enchant or deceive anyone who wanders into their woods, intent on bewitching men or cannibalizing children. Someone like this:

This image above is from Nicolas Roeg’s film adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches (1983), a telling example from modern literature which perpetuates the demonization and dehumanization of those women labeled witches. The gendered monsterization of certain women on the periphery of society—in particular midwives, spinster, healers and widows—had real world consequences. During the early modern witch-hunts throughout Europe, women were disproportionately the targets of witchcraft accusations and executions. Moreover, prophetic male mystics from the Middle Ages, such as Joachim of Fiore (1202 CE) and Nostradamus (1566 CE), were widely revered as wise men, whereas prophetic female mystics, such as Marguerite Porete (1310 CE) and Joan of Arc (1431 CE), are much more frequently burned at the stake under pretense of witchcraft and heresy. The early modern witch-hunts, which remain one of history’s largest scale gender-specific example of institutionalized misogyny and female persecution. Women were overwhelmingly the target of witchcraft accusations and trials in both Europe and New England, and historians such as Brian Levack estimate that there were over 100,000 trials and that “European communities executed about 60,000 witches during the early modern period,” making it the most significant and alarming historical instance of gendercide in Europe.

Ancient and medieval lore generally regards witches with suspicion and witchcraft with hostility. Indeed, in Old Norse-Icelandic sagas (c. 1100-1500 CE), witchcraft (known as seiðr) is almost always dangerous and frequently linked to heroes’ deaths. Much earlier, Medea is portrayed as sometimes helpful though oftentimes harmful, observable in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 CE). Similarly, Morgan Le Fay is an enigmatic character, who is primarily characterized as a great healer in early romances such as those by Chrétien de Troyes (1191 CE), though she is treated more pejoratively by the likes of later medieval authors such as Thomas Mallory in his Le Morte d’Arthur (1485 CE). Both Medea and Morgan contribute to the image of a glamorous witch, one which is balanced by the more regular image of the decrepit, wicked witch epitomized by Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters in Macbeth (1606 CE). Sometime witches are not one or the other, but rather both simultaneously hideous and enchanting, such as the witch in the “Wife of Bath’s Tale” from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1400 CE).

Witch-stereotypes, discussed at length by Levack, emphasize how witches operated on the fringes of society. Their magic is generally regarded as primarily folkloric and herbal in nature, derived from specific ingredients and powerful concoctions, connecting them to what Kieckheifer refers to as “natural magic” that centers on unlocking the occult powers of nature. Indeed, witches may be beautiful or ugly—but whatever the case they are almost always conniving and treacherous—a far cry from presentations of wizards as kind embodiments of timeless wisdom.

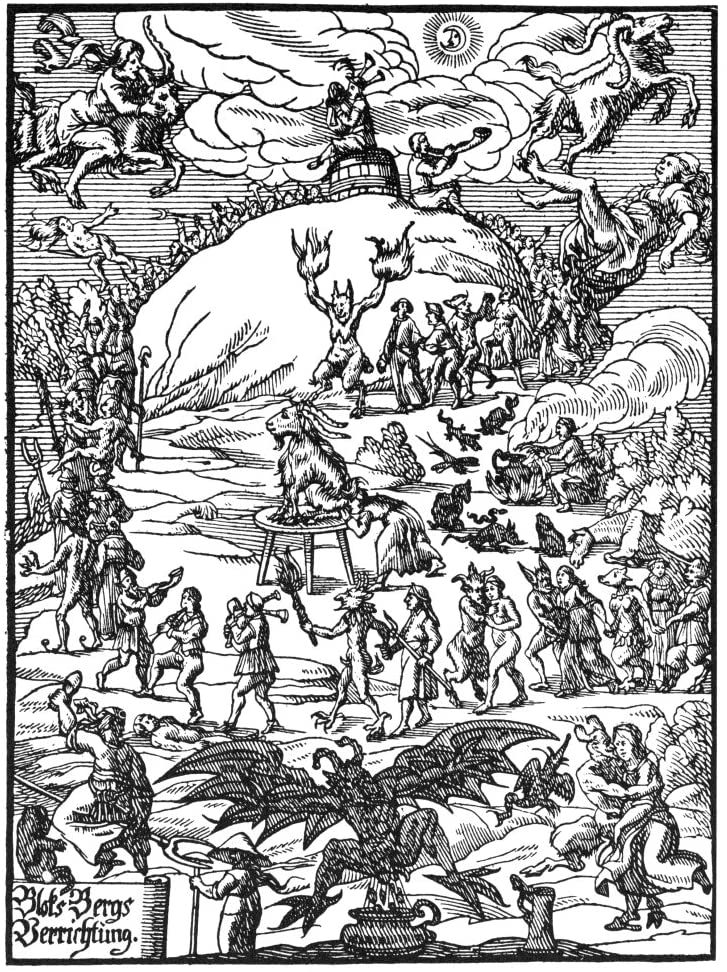

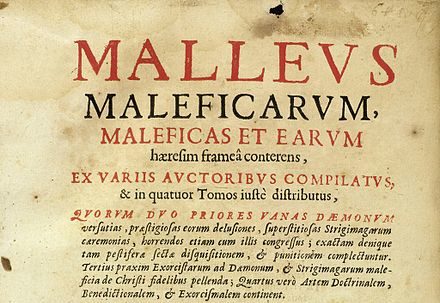

Although witches never got a fair shake, things get exceptionally worse following Jacob Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer’s publication of the infamous Malleus maleficarum “The Hammer of Witches” (1487), which codifies witch-stereotypes in an effort to provide an inquisitor’s guide to witch-hunting prior to the Protestant Reformation and the major outbreaks of witch-hunting hysteria in places like England and Germany. The Malleus characterizes witchcraft as a form of demonic magic and outlines specific behaviors and rituals in which witches allegedly engaged, in particular the dreaded witch’s sabbath, depicted as a massive gathering in the forest in which evil spells and orgies with demons were purportedly standard practice.

Although thousands of women and men were accused and executed under pretense of witchcraft across Europe, in the United States, witch hunting and hysteria is often discussed in isolation as a brief phenomenon resulting from a combination of religious fundamentalism and political rivalry in New England. This horrific episode in early American history was further popularized by Arthur Miller’s Crucible, which recounts the Salem witch trials. Although the American witch trials pale in comparison to their European counterparts, the increased racialization of witchcraft in the “New World” can be observed from the treatment of Tituba, an African slave and the first woman accused of witchcraft in New England, to later myths surrounding figures such as Marie Laveau, the famous Louisiana Creole herbalist, midwife and practitioner of Voodoo.

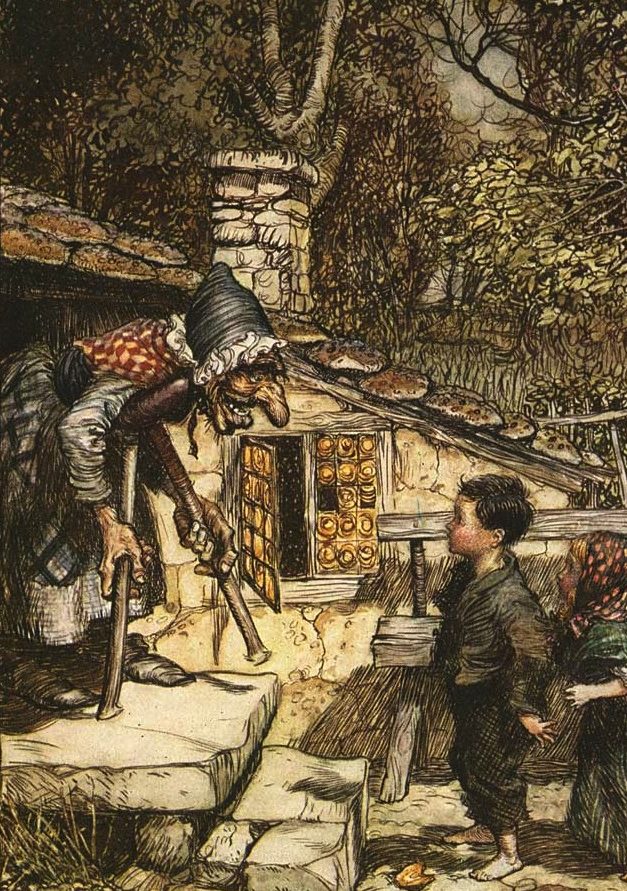

The standard, monsterized, racialized and genderized image of a wicked witch—crafted from a culmination of ancient, medieval and modern stereotypes—has expanded in contemporary popular culture, and white wizard male privilege looms as large as ever. Modern literary examples further demonize witches and folktales, such as Russian stories of the conflict between the benevolent winter-wizard Morozko, a grandfather winter character, and the notorious Baba Yaga, who remains one of the most popular witches in modern Russia. Again, the patriarchal image of a white wizard is complemented by his adversary, the wicked, old witch-woman who lurks in the forest and preys on children.

This blog aims to illustrate the magical double standards embedded in respective idolization of wizards and demonization of witches throughout Western literary history which persists today and are continually displayed in the visual rhetoric of modern representations of magic-using women and men.

One way to demonstrate this tradition of misogyny with respect to gendered magic, which I am identifying as wizard male privilege, is to view some depictions of witches and wizards from popular literature juxtaposed against each other:

Prospero and Sycorax from William Shakespeare’s Tempest:

Perhaps as important as Moses, Merlin or Odin in establishing wizard-stereotypes and white male wizard privilege is the character of Prospero from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. As his Weird Sisters epitomize literary witch-stereotypes, Prospero represents an archetypal wizard—a brilliant man of pure heart, who prizes learning and knowledge above all—and whose arcane knowledge allows him to control spirits of the island, like Ariel, and defeat the former ruler of the island—the evil and racialized witch Sycorax, who is mother to the monster Caliban. Like Salem’s Tituba, Sycorax represents an early modern racialization of witches, which served to uphold European colonialism, genocide and slavery during the early modern era.

The Wizard of Oz & the Wicked Witch of the West from Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz.

This classic pair are a distinctly American wizard and witch, and they are dramatized in one of the first color motion pictures (1939). Since the film played up the use of color, the prominent image of green-skinned witch—a racialization and monsterization of her—has become almost ubiquitous in visual depictions contributing to the development of witch-stereotypes in American popular culture. However, Baum’s The Wizard of Oz novel, which does not feature green-skinned wicked witches, also offers an alternative to witch-stereotypes by providing “good witches” to balance the wicked ones. These good witches are as beautiful and wonderful as wicked witches are hideous and horrific, and notably these good witches are white, while their wicked counterparts are non-white. While The Wizard of Oz includes the possibility of good witches, nevertheless to be regarded as other, weird or nonconformist is condemnable and “wicked” by definition of witch stereotypes and gendered beauty standards in the film, a point which invites further inquiry regarding the issue of gender normativity in images of “good” and “wicked” witches in the The Wizard of Oz.

Gandalf from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit & Jadis (the White Witch), from C.S. Lewis’ Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe:

Comparing Gandalf and Jadis is, of course, limited in so far as they are characters from different books by different authors. Nonetheless, Tolkien and Lewis—both members of the literary group known as the “Inklings”—in some ways share literary tastes and interests, being two of the most influential modern Fantasy authors and close friends. The Odinic Gandalf, perhaps even more than Merlin, serves as an archetypal wizard in modern literature and popular culture, while Jadis (better known as the “White Witch”) is the usurping “Queen of Narnia” who is simultaneously beauteous and hideous, but above all dangerous, like the Hans Christen Andersen’s Snow Queen upon whom she is based. Gandalf’s transformation from a “grey wanderer” to the “white wizard” marks the pinnacle of his divine power actualized by his Christlike death and resurrection. Both Gandalf and Jadis contribute significantly at an important time to the development of modern wizard and witch stereotypes in contemporary Fantasy literature.

Merlin & Mad Madam Mim from Disney’s Sword in the Stone:

Depictions of Merlin and Morgan Le Fay as magical adversaries have continued, and usually the standard wizard and witch stereotypes apply. However, in Disney’s adaption of T.S. White’s Once and Future King, Merlin’s rival sorceress, Mad Madam Mim, is even more stereotypical in her representation, following in line with a general trend in Disney films which repeatedly cast villainous women in these terms. The two nemeses engage in a “wizard’s duel” where they transform into various creatures and attack each other, and rather predictably, Mim cheats but Merlin nevertheless outsmarts her. Mim is by no means the only Disney witch, but rather just one iteration of many, and with very few—very recent—exceptions, in Disney films, witches are treacherous and evil.

Indeed, what Disney films have done in terms of upholding witch-stereotypes is plainly horrendous. From the earliest witch stepmother, the wicked queen from Snow White, to subsequent witches such as Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty, Ursula from Little Mermaid and Mother Gothel from Tangled, the evil witch-antagonist has been a featured favorite. The metamorphic woman—simultaneously seductive and decrepit—is a stock villain appearing frequently in Disney’s films, which regularly present sexist and racist depictions of witches and wizards. The witch-antagonist often represents a challenge to the established order: she is powerful and independent, which of course makes her dangerous. To my mind, this is probably the most egregious example of latent misogyny embedded in Disney’s films and the visual rhetoric undoubtedly continues to impact generations of girls and boys.

Disney has similarly upheld white male wizard privilege at virtually every turn. Disney antagonists are often racialized sorcerers, such as the ambitious royal vizier Jafar and Dr. Facilier “Mr. Shadow” from the Princess and the Frog (2009). Both are characteristically evil, while older and whiter magic-users like Merlin and King Trident from the Little Mermaid (1989) are depicted as distinctly “good” in that they are patriarchal stewards of the status quo and established order. This is a blatantly observable trend of white supremacy in Disney films, which repeatedly portray racialized and orientalized spellcasters as villains.

Schmendrick & Mommy Fortuna from Peter Beagle’s Last Unicorn:

This classic Fantasy story, brought to motion pictures by Rankin & Bass, centers on the journeys of a wandering unicorn in search of her kin. Along the way, an old witch—Mommy Fortuna—enchants the unicorn with a spell and captures her in order to use the creature in her “Midnight Carnival” as a spectacle. Mommy Fortuna is a classic crone, complete with an ominous raven and a brutish henchman. However, luckily for the unicorn, there is also a magician, the young and fumbling Schmendrick, who not only helps her escape from Mommy Fortuna (who is eaten by a harpy also freed during their escape), but is her trusted companion, advisor and friend throughout her travels. He serves her faithfully until at last they discover the truth about whether or not she is the last unicorn. Schmendrick is a bit of a fool but good, through and through, while Mommy Fortuna is greedy, fraudulent and opportunistic.

Albus Dumbledore and Bellatrix Lestrange from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter:

J.K. Rowling more than any modern Fantasy author explores, adapts, and upholds wizard and witch-stereotypes in both the book and film versions of the Harry Potter series. In her second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, when describing the origins of Hogwarts, Rowling briefly contextualizes her magical school with a historical reference to the early modern witch-hunts, stating that “They [Godrich Gryffindor, Helga Hufflepuff, Rowena Raven Claw and Salazar Slytherin] built this castle together, far from prying Muggle eyes, for it was an age when magic was feared by common people, and witches and wizards suffered much persecution” (“Chapter 9: The Writing on the Wall”). While she may be emphasizing that women received the vast majority of the accusations and persecution, by listing “witches” before “wizards” in this passage, this point is never made explicitly. Nevertheless, Rowling elevates witches to their rightful place alongside their distinguished wizard counterparts in halls of Hogwarts and the broader wizarding world of Harry Potter.

However, it is worth noting that, although Rowling is a woman, both her main protagonist and the most powerful of her “good” wizards are male magic-users. In her characterization of the wise headmaster and superstar wizard, Albus Dumbledore, she reinforces every white wizard stereotype, following directly in Gandalf’s footsteps. On the other hand, Belletrix Lestrange—whose French-sounding name recalls the medieval Morgan Le Fay—represents a caricature of witch-stereotypes as she is one of the most murderous of Voldemort’s evil gang known as Death-eaters. Of course, it could be argued that Dumbledore and Lestrange represent as likely a pairing as professor Minerva McGonagall and Voldemort (though in reverse), which may be true, but even in the later comparison male privilege is maintained as the dark lord (although an equal match for Dumbledore) could easily outperform even the most powerful witch at Hogwarts.

The Greenseer (Three-Eyed Raven) & Melisandre from George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire:

In George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire and HBO’s Game of Thrones television series based on the books, again usual tropes are employed with respect of wizards and witches. The mystical and mysterious Greenseer, who resides in the roots of a Weirwood tree far north of the Wall appears like Merlin in his cave, becoming one with the land itself. In the film adaptation, he is primarily known as the “Three-eyed Raven” because he appears frequently to Bran Stark as a raven with a foreseeing third eye. The Greenseer is a traditional wizard in many ways: he is an ancient, wise and thoroughly “good” mentor, who selflessly sacrifices himself to save mankind and pass on his position to Bran.

Alternatively, the “Red Woman” Melisandre is a fire priestess of Rh’llor, the monotheistic God of Light, and she is a much more ethically complicated figure. Like her shape-shifty literary predecessors, Melisandre is sexualized and seductive, but she is also ancient, and her beauty is, in truth, nothing more than a glamor illusion as her authentic form is that of an old crone. Although she seems to have some regret by the end of the film series, Melisandre, nevertheless, burns many innocent people in the name of her religion—at times even immolating children—to gain power and favor with her god. For Melisandre, the ends always justify the means, as she is willing sacrificing whomever she believes benefits her cause most. Her final self-combustion marks her personal defeat but does not save or benefit anyone else.

Deckard Cain and the witch Adria from Blizzard’s Diablo:

Wizard and witch stereotypes have unsurprisingly infiltrated the world of Fantasy gaming as well. In Blizzard’s Diablo game, there is a classic white wizard, Deckard Cain, who is introduced as an omniscient loremaster able to identify any magical item and weapon. Cain starts off seemingly rather old and feeble, if knowledgeable, but in each iteration of Diablo, he gets wiser and more powerful, counted as the “last Horadrim” and final member of this guild of arcane scholars. His character is a fixture of the Diablo games, where he repeatedly serves as a steadfast white wizard figure.

After raising Adria’s orphaned daughter, Leah, “Uncle Deckard” is rescued by the player in Diablo III and once more offers his sagely wisdom. Cain’s noble death at the end of Act I is the direct result of his refusal to conceded to the witch Magda’s demand that he “use his Horadric powers” to reforge a heavenly sword of the angel, Tyrael. Magda is represented as a Maleficent-like fairy-witch, and she ultimately kills Cain and kidnaps the wounded angel. She reappears later as a game boss for the player to battle. After Leah unleashes a magical blast causing Magda to retreat, Cain uses his final ounce of strength to save the world by remaking the angel’s sword, a feat only a Horadrim could accomplish, and the player is then charged with the task of uniting the celestial weapon with its wielder.

Adria, the witch who lives in her hut at the edge of the village, Tristram, experiences a very different characterization. She starts off as essentially a potion merchant, who seems altogether neutral and thereby helpful to the player. Adria later returns to the storyline in Diablo III, where her character takes a grim turn for the worse into misogynistic witch-stereotypes. Adria is reportedly impregnated by the player character from the original Diablo (assumed to be male, despite a female rouge character option in the first game), and is thereby sexualized as often occurs with representations of witches. After pretending to support the player’s efforts, Adria unveils that she copulated with Diablo himself and that Leah is therefore demonic offspring.

This aligns Adria’s character with prescriptions of witches’ behavior in the Malleus, especially the section of the treatise that purports to answer a blatantly misogynistic—fantastical and grotesque—theological question: Quo ad maleficas cum daemonibus concurrentes: Cur mulieres amplius inueniantur hac haeresi infectae quam viri “With respect to witches copulating with demons: Why is it that women are more susceptible to be infected by this heresy than men?” (Part I, Question VI). After Leah’s big paternity reveal, Adria uses a black soulstone and sacrifices her own daughter to bring Diablo back into the moral world. Although the witch escapes, in the subsequent expansion pack, Reaper of Souls, she meets her end after transforming into a demon and fighting against the player as a game boss.

Also, in Diablo III, there is the inclusion of a peripheral character Zoltun Kulle, who is a mad wizard striving to become a dark lord. Kulle comes from the kingdom of Caldeum, represented as a stereotypical Middle Eastern realm and named “the jewel of the East.” From the onset, Kulle is depicted as an evil, Jafar-like sorcerer. Although Kulle was a formidable wizard in life and one of the founders of the Horadrim, he is corrupted by the power of the black soulstone and becomes a monster, who continues to haunt and terrorize from beyond the grave. Like with Adria, after working for a while together, the orientalized wizard betrays the player and becomes a game boss. Indeed, Diablo III upholds—with the characters of Deckard Cain, Adria and Zoltun Kulle—virtually every gender and racial stereotype with respect to competing characterizations of magic-users in Fantasy literature and popular medievalism.

These selected examples are but a few, and there are abundant others that could be added to further demonstrate the sexist and racist rhetoric embedded in depictions of wicked witches, dark sorcerers, and white wizards. From just this brief and incomplete review of literary representations of witches and wizards, it is clear that sexist and racist stereotypes have not only endured but have deepened since ancient and medieval times. White wizard male privilege continues to thrive in contemporary Fantasy literature, film and games. This cannot be ignored because these stock characterizations reinforce problematic gender and racial stereotypes. They misrepresent, and in a sense seem even to validate, the historical tragedy of early modern witch-hunting in Europe—one of the most widespread and gendered-specific persecution of women in history. Like the “dark lord” and evil sorcerer exceptions, the modern “good witch” exception relies largely on visual rhetoric, primarily drawn from the character of Glinda, who is coded white and defined in contrast to the green Wicked Witch of the West in the Wizard of Oz film (1937).

In modern times, the new age religion known as Wicca offers a feminist reclaiming and rebuke of conventional characterization of witches by understanding witchcraft instead as a symbol of female autonomy and empowerment. This theme is popularized in contemporary revisionist literary reimaginations such as Gregory Maguire’s revisionist novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West which casts Glinda as the villain and the once wicked witch is given the name Elphaba, transformed into an underdog protagonist—the misunderstood victim of systemic prejudices and unfortunate circumstances. Of course, even very recent films featuring witches that in some ways seem to fall into this recent literary trend, such as Robert Egger’s The VVitch: A New England Folktale (2015) and Aguirre-Sacasa’s Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (2018), perpetuate many problematic witch-stereotypes,

While reparative portraits of wizards and witches do exist—such interpretations mark the exceptions that prove the rule. The internalized rule remains one of white wizard male privilege, a sexist and racist double-standard demonstrated by the uneven and repeatedly monsterized treatment of witches and female magic-users.

While Wicca and other modern practices of witchcraft seek to redefine witches a symbol of woman power, on the other hand, the way in which “wizard” has become appropriated by certain groups, who seem to recognize the implicit sexist and racist rhetoric conveyed by images of white male wizards in modern medievalism, is much more troubling. As has been widely discussed, especially by medievalists of color, white supremacists and alt-right groups readily appropriate medieval images and symbols in their efforts to perpetuate the erroneous narrative that the Middle Ages was a homogeneous historical period. This myth has been repeatedly debunked by scholars but nonetheless persists especially in groups who identify as white nationalist. Indeed, the most infamous American white supremacist group—the nefarious Klu Klux Klan—has long been leveraging this fallacious rhetorical presentation of the Middle Ages as uniformly white since the end of slavery in the United States, and among their most exalted titles include the designations of Grand Wizard and Imperial Wizard.

Wizard will likely remain a fixture in Fantasy literature and popular medievalism. And, until there is more room for wizards of every color in the genre, and witches that can be both good and powerful without prescribing to heteronormative gender stereotypes, white wizard male privilege—a literary example of both misogyny and white supremacy—will no doubt persist.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Selected Sources

Baum, Frank. The Wizard of Oz (1900).

—, & Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The Wizard of Oz [film] (1939).

Beagle, Peter. The Last Unicorn (1968).

—, & Rankin & Bass. The Last Unicorn (1982).

Blizzard Entertainment. Diablo (1997).

—. Diablo II (2000).

—. Diablo III (2012).

—. Diablo III: Reaper of Souls (2014).

Dahl, Roald. The Witches (1983).

Disney [The Walt Disney Company]. Snow White (1937).

—. Sleeping Beauty (1959).

—. The Sword in the Stone (1963).

—. Little Mermaid (1989).

—. Aladdin (1992).

—. The Princess & the Frog (2009).

—. Tangled (2010).

Lewis, C.S. The Chronicle of Narnia (1950-1956).

—, & CBS. The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe (1979).

—, & Disney [The Walt Disney Company] The Chronicle of Narnia [film series] (2005-2008).

Martin, George R.R. Song of Ice and Fire (1996-2011).

—, & HBO. Game of Thrones (2011-2019).

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter (1997-2007).

—, & Warner Brothers. Harry Potter [film series] (2001-2011).

Miller, Arthur. The Crucible (1953).

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest (1611).

—. Macbeth (1606).

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Hobbit (1937).

—. The Lord of the Rings (1954).

—, & Rankin & Bass. The Hobbit (1977).

—, Peter Jackson, & Warner Brothers. The Lord of the Rings [film series] (2001-2003).

—, Peter Jackson, & Warner Brothers. The Hobbit [film series] (2012-2014).

Further Reading

Birks, Arran. “The ‘Hammer of Witches’: An Earthquake in the Early Witch Craze.” The Historian (2020).

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Kickhefer, Richard. European Witch Trials: Their Foundations in Popular and Learned Culture, 1300-1500. Routledge, 1976.

—. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Kim, Dorothy. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In the Middle (2017).

Lewis, Jone Johnson. “Malleus Maleficarum, the Medieval Witch Hunter Book.” ThoughtCo (2019).

Levack, Brian. The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe. Routledge, 2016.

Lomuto, Sierra. “White Nationalism and the Ethics of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Young, Helen. Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness. New York: Routledge, 2016.