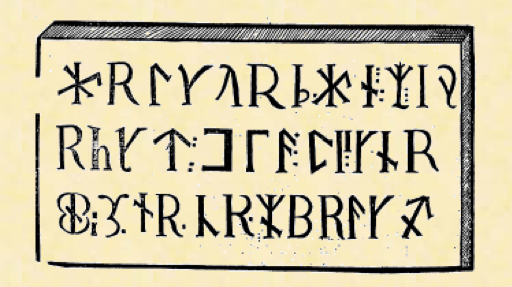

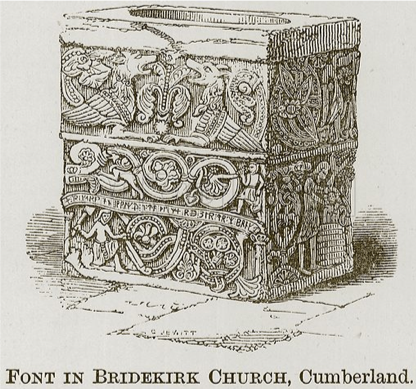

In the mid-twelfth century, a stoneworker in the far northwest of England at Bridekirk, Cumbria cut a lavishly-decorated baptismal font with reliefs of dragons, mysterious figures, and, curiously, a line of runic writing. By the early modern period, the characters on the Bridekirk font were nothing but strange. Early English historian and chronographer William Camden, who included a sketch of the runic inscription in the 1607 edition of his Britannia, declared himself perplexed: “Quid autem illae velint, et cuius gentis characteribus, ego minime video, statuant eruditi.”[1]

First published in 1586, Camden’s massive historico-chronographical Britannia went through six editions in the author’s lifetime, and Camden continually updated and expanded the text, augmenting it with maps and diagrams, such as the rendition of the Bridekirk runes seen below. The last Britannia edition on which Camden collaborated was a 1610 English translation by Philemon Holland, who translates: “But what they signifie, or what nations characters they should be, I know not, let the learned determine thereof.” Camden’s uncertainties cut straight to the heart of the matter: whose runes are these? and what do they mean?

In the more than 400 years that have passed since the publication of Camden’s Britannia and despite the best efforts of the eruditi, no simple answer has been found to either of Camden’s questions, the first of which I’ll consider in today’s post. Whose runes are these?

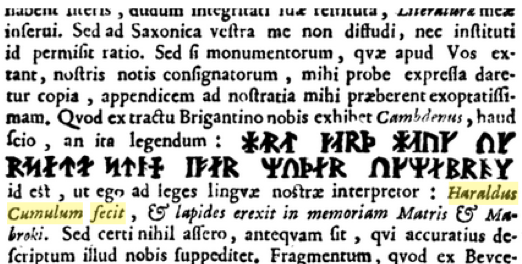

Danish antiquarian Ole Worm learned of the inscription from the Britannia and included his own version of the runes in a 1634 letter to one Henry Spelman:

Translation: But if a well-printed text of the monuments inscribed with our characters that exist [in England] is sent to me, they would make up the much-desired appendix to those from our country. As far as the one Camden shows us in his book Britannia, I hardly know whether it can be read: [RUNES] That is, as I interpret it according to the laws of our language: “Harald made [this] mound and set up stones in the memory of [his] mother and Mabrok.” But I claim nothing as certain until someone can supply us with a more accurate description.[2]

At other times the inscription has been claimed as English. The description of the Bridekirk font in Charles Macfarlane’s Comprehensive History of England, first published in 1856, praises the “ingenuity of design and execution” of the font and notes its “Saxon inscription.”[3]

Modern scholars agree with Worm that the incised characters are, in the main, Scandinavian. But the inscription is not wholly so: the text employs a few non-runic, decidedly English characters, including ⁊, Ȝ, and a bookhand Ƿ. Moreover, the language is not the Norse one might expect from Scandinavian runes but rather English:

Ricard he me iwrokte ⁊ to þis merð ʒer ** me brokte.[4]

Richard crafted me and brought me (eagerly?) to this splendor.

So if the runic inscription is neither fully Norse nor fully English, whose runes (cuius gentis) are they? While Charles Macfarlane claimed them as “Saxon” and Worm counted them as Scandinavian, the runes are actually neither but rather the product of a mixed society continuing to encode both English and Norse cultural practices on stone. Most literally the runes represent phonological values and a particular message, but for most of the font’s history the place of these symbols in cultural memory – whose runes they have become – has been just as important as what they originally meant. The cultural equivocality of the Bridekirk inscription is emblematic of larger ambiguities involving Anglo-Scandinavian ethnicity and culture as imagined by the post-Hastings medieval English. These ambiguous cultural signs, later re-imagined in the early modern period, raise the question of what it meant to be Anglo-Norse in an Anglo-Norman world.

Rebecca West, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

[1] William Camden, “William Camden, Britannia (1607) with an English Translation by Philemon Holland: A Hypertext Critical Edition,” ed. Dana F. Sutton (The Philological Museum, 2004), Descriptio Angliae et Walliae: Cumberland, 7.

[2] Ole Worm, Olai Wormii et ad eum doctorum virorum epistolæ, vol. 1 (Copenhagen, 1751), Letter 431. This translation is my own.

[3] Charles MacFarlane, The Comprehensive History of England :Civil and Military, Religious, Intellectual, and Social : From the Earliest Period to the Suppression of the Sepoy Revolt, Rev. ed. (London, 1861), 164.

[4] The transliteration above is based on that of Page, who reads “+Ricarþ he me iwrocte / and to þis merð (?) me brocte.” R. I. Page, Runes (University of California Press, 1987), 54.