Along oyster beds, sand dunes, and marshy coastal lowlands rise the church spires and walls of a medieval coastal city. This isn’t Northumbria’s Holy Island or Normandy’s Mont-St-Michel, though. This is the City of St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest city continuously occupied by Europeans and African-Americans in North America. This settlement on Florida’s First Coast predates the arrival of the Mayflower pilgrims at Plymouth in 1620 and even the 1607 founding of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement.

The Age of Reconnaissance

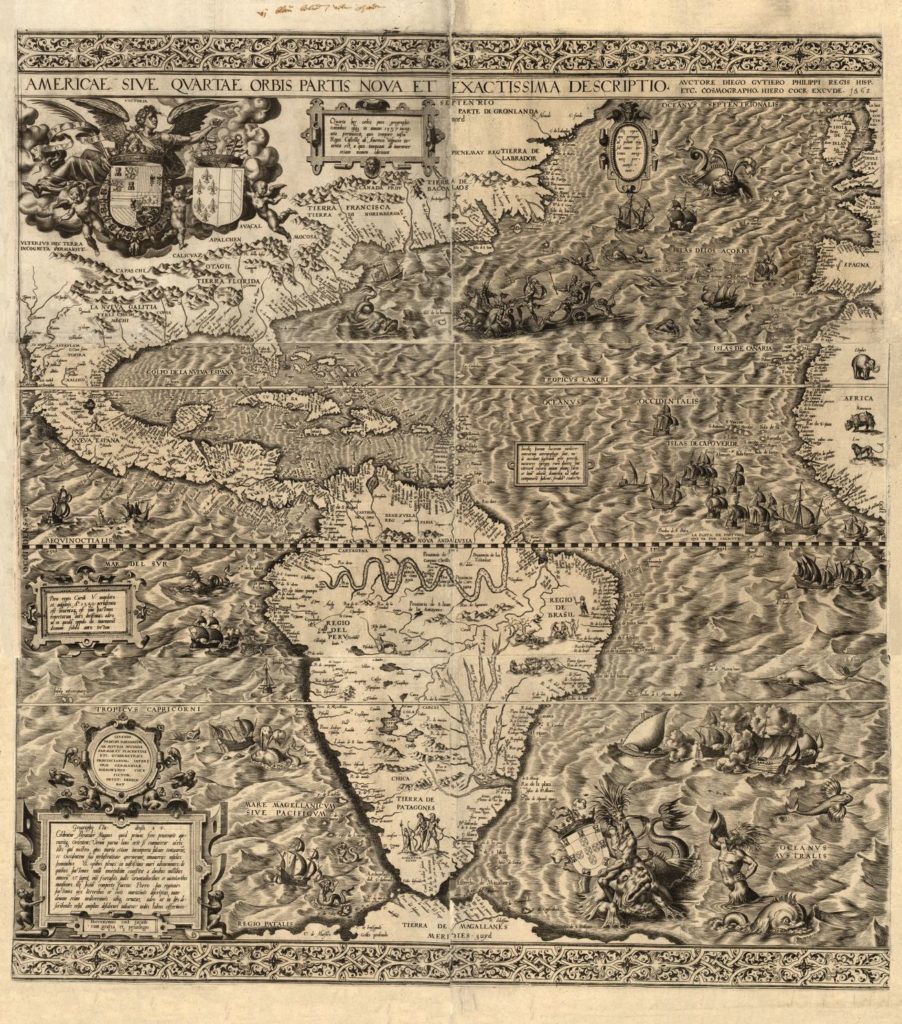

St. Augustine was founded by the Spanish in 1565 as part of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century European push to discover, explore, and settle new lands beyond Europe. This “Age of Reconnaissance” is one of the hallmarks for historians of the transition from the late Middle Ages into the Early Modern period in Europe.

Historian J. H. Parry describes the medieval beginnings of this push, especially in Spain:

“The initial steps in expansion were modest indeed: the rash seizure by a Portuguese force of a fortress in Morocco; the tentative extension of fishing and, a little later, trading, along the Atlantic coast of North Africa; the prosaic settlement by vine and sugar cultivators, by log-cutters and sheep-farmers, of certain islands in the eastern Atlantic. There was little, in these early- and mid-fifteenth-century ventures, to suggest world-wide expansion.”

In the later fifteenth-century, though, this expansion indeed exploded globally. [1] The desire to expand wealth through acquisition of new lands, slave labor, and precious metals and stones, as well as the desire to convert any newly-discovered peoples to Catholicism, were powerful enticements for Spain to explore. Developments in nautical navigation, map-making, and ship technology made exploration possible.

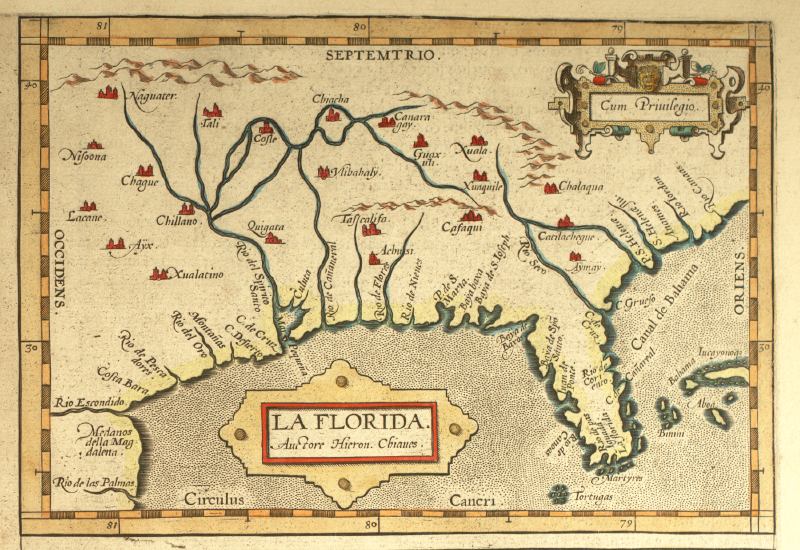

Spain’s first encounter with the Florida coast came during the explorations of a medieval Spaniard, Juan Ponce de Léon (b. ca. 1460 in Léon, Spain). In early April 1513, with a license from Spain’s King Ferdinand II (1452–1516), Ponce de Léon sailed from Puerto Rico looking for Bimini (the Bahamas) and, legend has it, the Fountain of Youth. He found Florida instead, landing somewhere between St. Augustine and Melbourne Beach.

Claiming it for Spain, he gave the supposed island its Spanish name of La Florida, or Pascua Florida, depending on which source you look at; both names suggest Ponce de Léon was struck by the abundance of flowers he must have seen. (“Pascua Florida Day” is a state holiday and is celebrated on or around April 2nd each year.) He then sailed southward around the peninsula to explore further. [2] Ponce de Léon returned to Spain and procured Spain’s consent to colonize the New World; thus Spanish settlement began. [3]

The Settlement of St. Augustine

Fifty-two years later, with a new French settlement threatening Spain’s claim to this territory, King Philip II commissioned Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to colonize the area and remove the French. On August 28, 1565, the feast of St. Augustine, Menéndez, his crew, soldiers, and settler families, over 2,000 souls traveling in 11 ships, sighted this land from sea and named it after the saint.

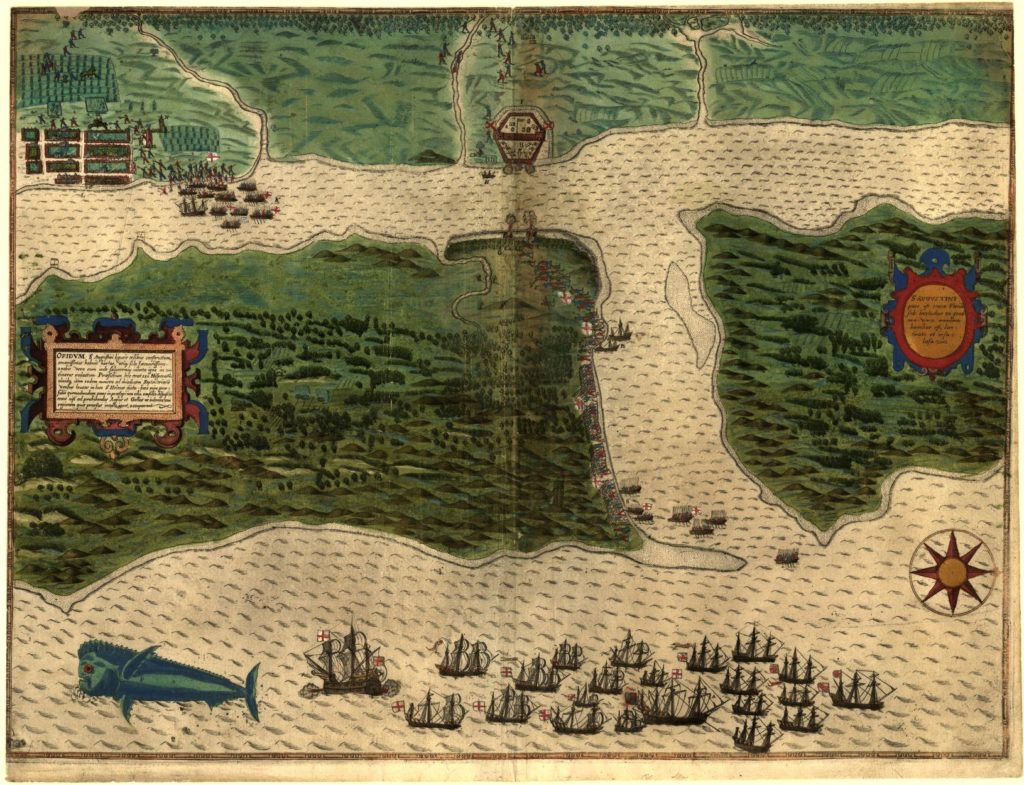

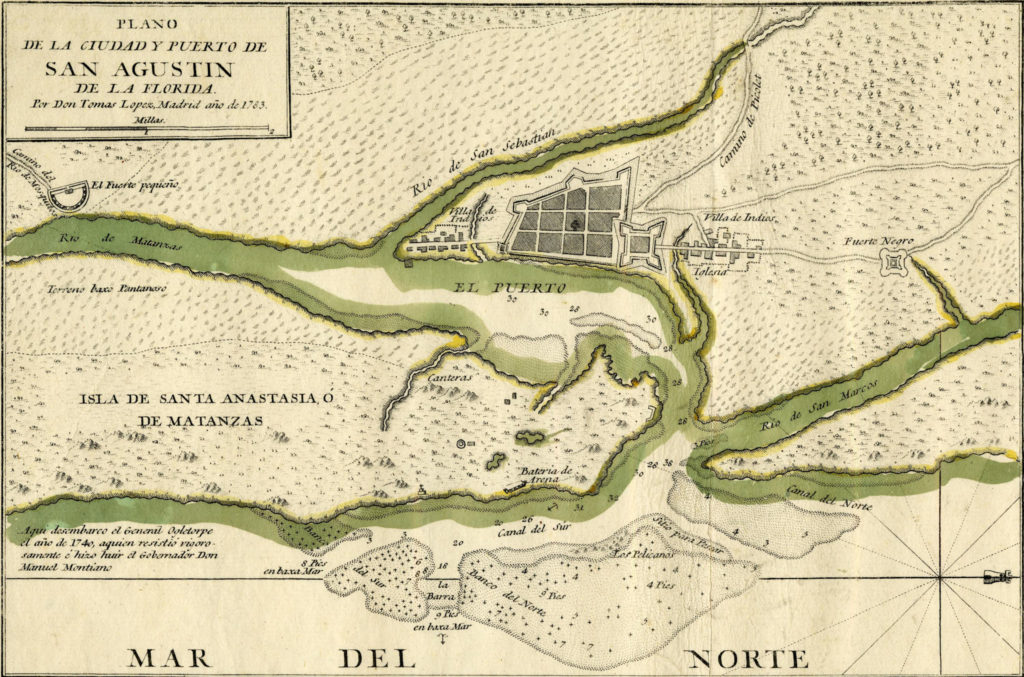

Menéndez and the settlers built defenses (pictured below, top center, which St. Augustinians replaced a little over a hundred years later with a stone fort, the Castillo de San Marcos) and laid out homes and plots for cultivation (pictured below, top left). St. Augustine was thus established and remained a hub of Spanish Florida, both for military defense and as a home base for Catholic missionaries.

Sadly, the next 50 years saw the Spanish settlers nearly annihilate the native Timucuan peoples of the area through disease and war. [4] The Spanish did aid escaped slaves, though, albeit conditionally. As early as 1687, Blacks escaping slavery in the nearby British colonies of Georgia and the Carolinas sought asylum in St. Augustine, the second-largest town in the southern colonies. [5] They received freedom in exchange for converting to Catholicism and, for men, joining the Spanish military. (In 1738 this settlement became a fortified town, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first free Black community in the colonies, at the north end of St. Augustine. The settlement is now commemorated as Fort Mose Historic State Park.) [6]

St. Augustine’s Coat of Arms

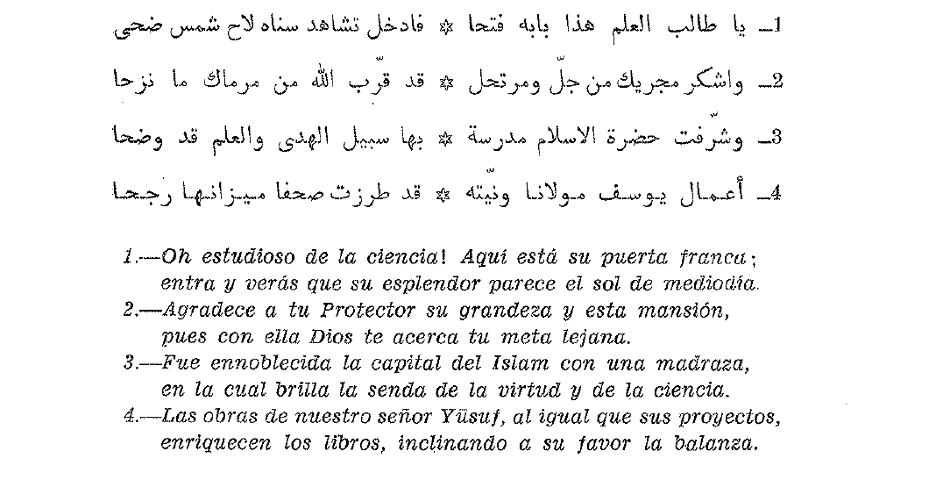

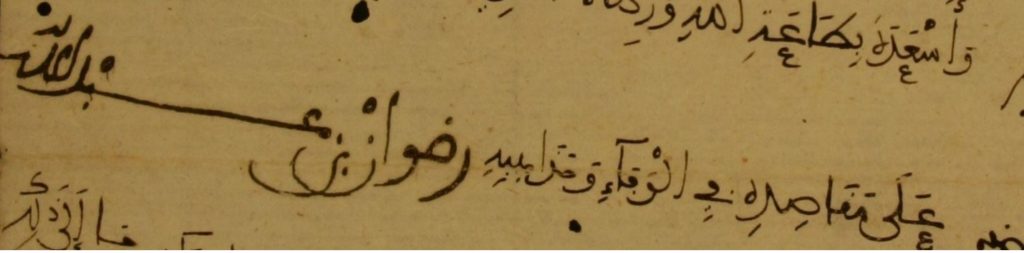

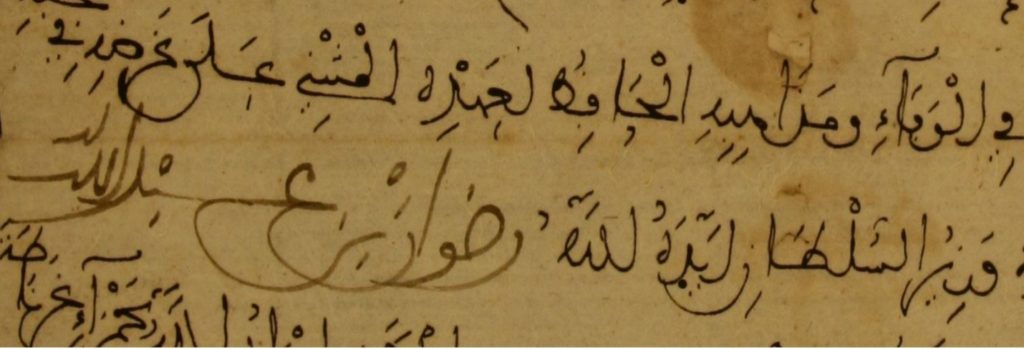

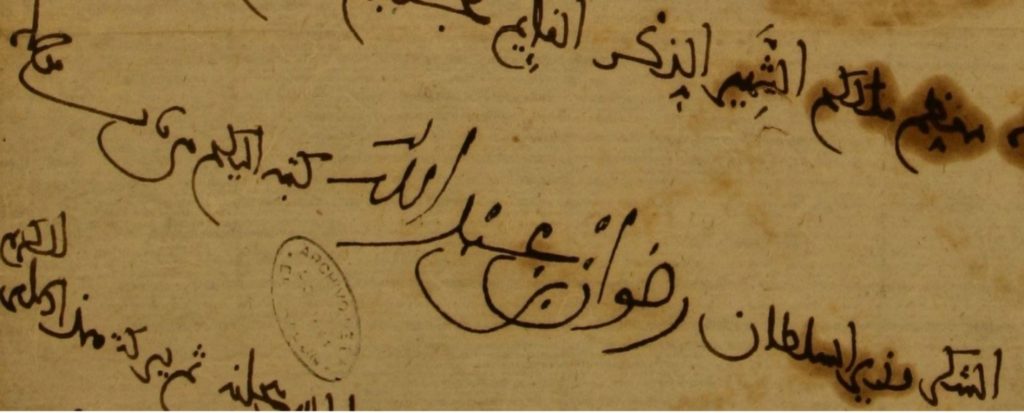

The later settlers of St. Augustine remained close to their medieval and colonial Spanish roots. In 1715, in fact, the city residents petitioned King Philip V of Spain for a coat of arms of their own, to reflect that heritage (they had previously used a version of the coat of arms of Castile and León, which appears on a lintel in the Castillo de San Marcos). They wrote to the king “to grant to them for arms, a ‘flor de lis, lion, castle and strong arm with cross in the middle’ and the title ‘Most Loyal and Valorous’ for their faithful and courageous service to Spain.” [7]

Philip did indeed grant the request, but neither the news nor the design of the coat of arms reached the city. In 1911 the City renewed its request with Juan Carlos I, King of Spain. Vicente de Cardenas y Vicent, Herald, King of Arms, Dean of the Corps of Heralds for Spain, informed St. Augustinians that indeed, the Coat of Arms had been granted on November 26, 1715, along with the title of “Most Loyal and Valorous” city. [8]

St. Augustine’s coat of arms contains the requested elements displayed on a shield, all topped by a crown. The seal and its elements draw on the medieval tradition of heraldry, which developed in Europe in the eleventh century as a way to visually distinguish and identify armor-covered knights on a battlefield. [9] In the next century heraldry grew to encompass family identity and then shortly after corporate identity, such as for monasteries, universities, and towns. [10]

St. Augustine’s seal visually marks the city’s medieval history and Spanish heritage as well as its city-hood (signified by the crown above the shield). In particular, the shape of the coat of arms’s shield is medieval and its golden cross signals the city’s Christian origins; the golden castle of Castile and the purple lion of León call back to the city’s Spanish heritage. St. Augustine proudly employs this coat of arms and crown on their city seal today, at a gateway that greets visitors to the city.

Join me later this summer for the second part of this series, when we’ll take a deeper dive into the medieval heritage of the city that you can still enjoy today!

About the Author

Dr. Hall earned her Ph.D. in Medieval English Literature from the University of Notre Dame and her M.A. and B.A. in English Literature from the University of Georgia. She has authored a number of publications including essays in Journal of the Early Book Society, Early Middle English, and History of Education Quarterly. She is also a native Floridian who enjoys defending her claim that Florida has a medieval past. She’s written about her home state’s early history since her first historical fiction novella, Gold Coast (1997), about the Spanish exploration of Florida.

Email meganjhall@nd.edu

Twitter @meganjhallphd

Further Reading

“Spanish Armorials” by the Heraldry Society

“The Arms of the Spanish Kings, 1580–1666,” Notre Dame Rare Books & Special Collections

“Genealogía y Heráldica,” from the Biblioteca Nacional de España (the National Library of Spain

Design your own heraldry or coat of arms!

Works Cited

[1] J. H. Parry, The Age of Reconnaissance: Discovery, Exploration, and Settlement, 1450–1650, pg. 15.

[2] “Native History: Ponce de Leon Arrives in Florida; Beginning of the End,” Indian Country Today (online), 2 Apr 2017; updated 13 Sep 2018.

[3] “Juan Ponce de León: Spanish explorer,” from Encyclopaedia Brittanica.

[4] “Timucua,” in “Cultural Histories,” Peach State Archeological Society.

[5] Jane Landers, “Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose: A Free Black Town in Spanish Colonial Florida,” The American Historical Review 95.1 (Feb 1990): 9–30.

[6] “The Fort Mose Story,” Fort Mose Historical Society.

[7] Mayor’s Proclamation, City of St. Augustine

[8] Mayor’s Proclamation, City of St. Augustine

[9] For a discussion of the development of heraldry in Spain, see the 2007 doctoral thesis by Luis Valero de Bernabé y Martín de Eugenio, “Análisis de las características generales de la Heráldica Gentilicia Española y de las singularidades heráldicas existentes entre los diversos territorios históricos hispanos.”

[10] Learn more about heraldry in Europe and around the world in “The Scope of Heraldry,” Encyclopædia Brittanica, and more about heraldry in Spain.