For Spain and North Africa, the late medieval period (ca. 1250-1500) was a tumultuous era that was characterized by political turmoil and mass violence. It was also the period that witnessed one of the greatest bursts of cultural efflorescence, intellectual creativity and administrative-political innovation in the region. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the cities of Toledo, Seville, Granada, Fez and Tunis, not unlike the city-states of Renaissance Italy during the same period, produced some of the most remarkable scholars and intellectuals in the history of the Western Mediterranean, despite the numerous challenges of the era. It was also the period that witnessed the rise of some of the most remarkable pieces of architecture in the region. One of the most iconic monuments associated with this period is the Alhambra, the royal and administrative center of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada between the 13th and 15th centuries. Since the Middle Ages, there has been no shortage of interest in this palace-fortress complex, its monumental scale and its exquisite craftsmanship.[1]

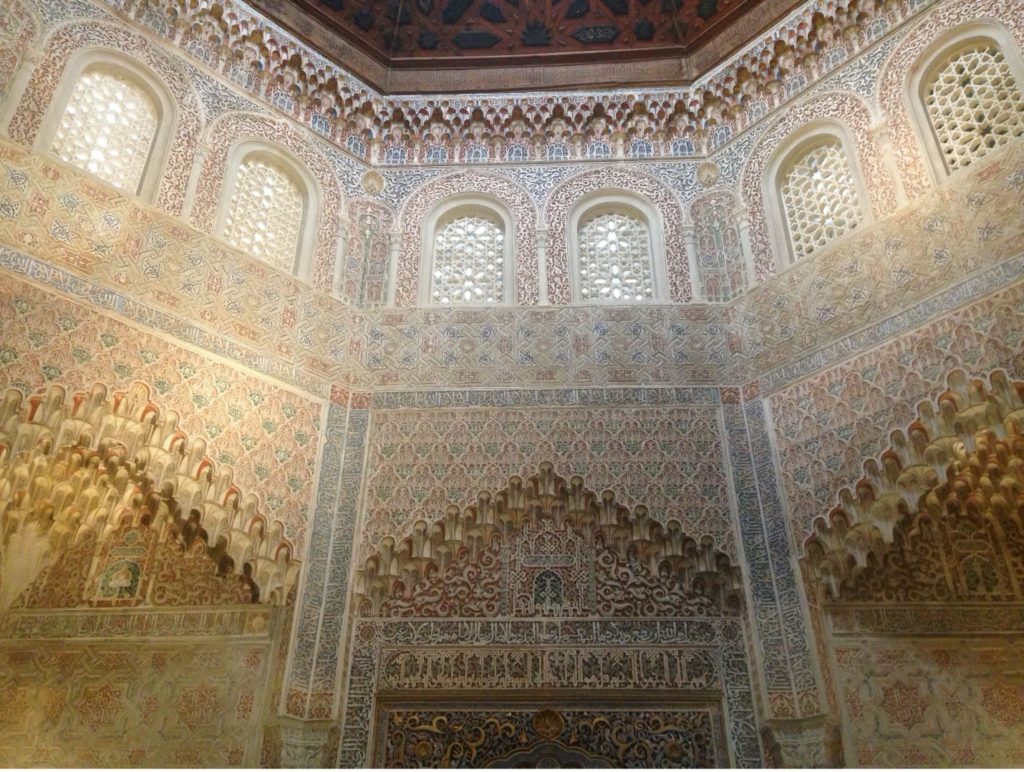

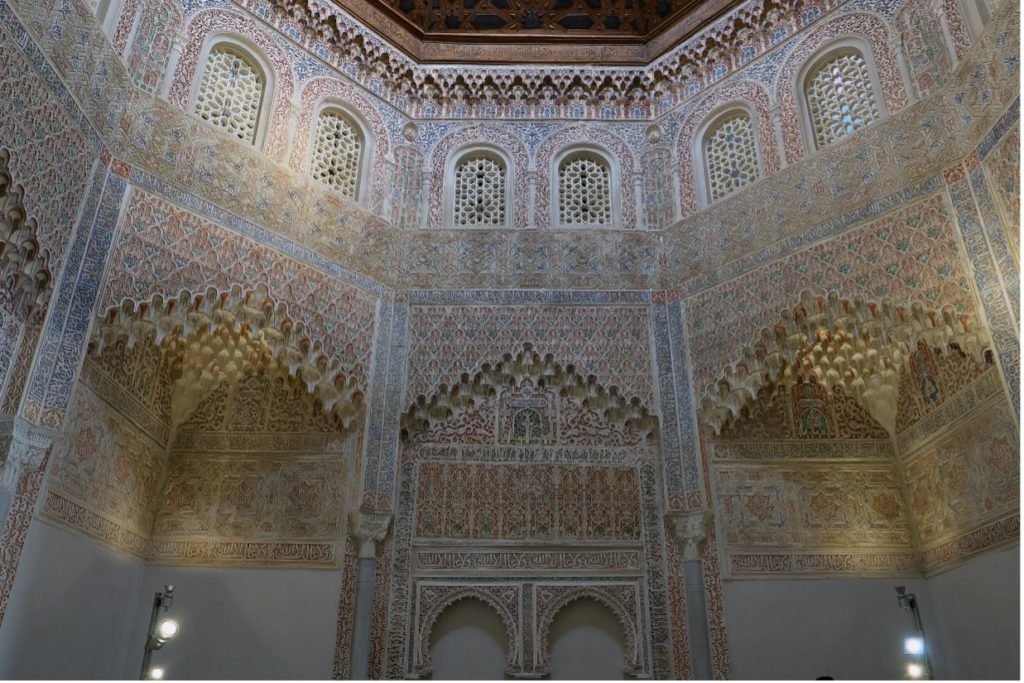

The history of another architectural and cultural gem from 14th-century Granada, which remains relative little-known beyond a small circle of specialists, is concealed behind an 18th-century Baroque façade behind the Great Cathedral of Granada: the Nasrid College (al-madrasah al-naṣriyyah), constructed in April 1349.

The Nasrid College was a rare example of a madrasah constructed in medieval al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia).[2] This structure, which was only excavated and restored over the past several decades and finally opened to the public in 2011, provides important insights into the intellectual, social and political history of Nasrid Granada during the 14th century. This short post seeks to provide an overview of the emergence of the Nasrid College, with particular attention to the cultural, political and intellectual context in which it emerged.

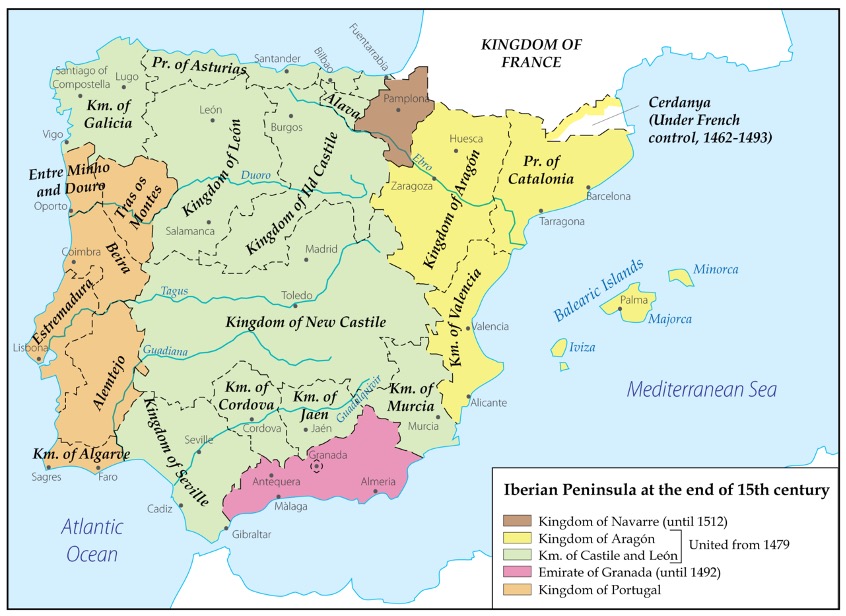

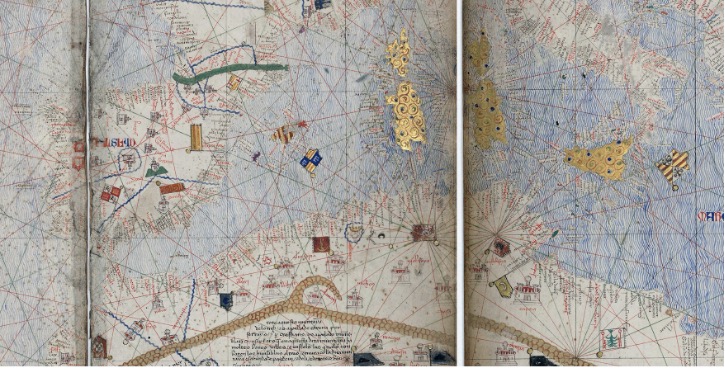

Nasrid Granada, the last surviving Muslim polity in medieval Iberia, was a borderland city-state entrenched in the farthest reaches of the Islamic world, between Europe and North Africa, yet closely connected and integrated within both Latin Christendom and the Islamic world. The Muslim-Christian borderlands during this period were characterized by intermittent frontier warfare and shifting alliances between Nasrid and Castilian rulers, the emergence of a bilingual nobility (conversant in Romance as well as Arabic), and the permeability of the frontier, which facilitated the passage and migration of mercenaries and merchants, renegades and refugees, scholars and slaves between the Islamic world and Latin Christendom.

Over the past several decades, there has been a substantial body of scholarship that has treated various aspects of the political, intellectual, cultural and social history of Nasrid Granada demonstrating the various ways that this polity and its inhabitants were shaped by this broader borderland context.[3] By the 14th century, the Kingdom of Granada encompassed one of the most urban and diverse populations in late medieval Iberia. The mass migration of thousands of Andalusi Muslims to Granada in the wake of the Castilian, Portuguese and Aragonese conquest of Islamic Spain transformed it from a regional urban center into a thriving metropolis and one of the largest cities in the western Islamic world.

Recent studies have challenged the conventional narrative of Nasrid decline and isolation by illustrating Granada’s integration into the extensive intellectual, mercantile, commercial and diplomatic networks that characterized the late medieval Mediterranean world. The various communities of Christian merchants and mercenaries, particularly from Genoa, Castile and Aragón, [4] that were established across the Nasrid kingdom between the 13th and 15th centuries often served as cultural intermediaries and conduits for the circulation and exchange of ideas between Latin Christendom and the Islamic West. The population of Nasrid Granada was characterized by social and cultural heterogeneity. The Andalusi Muslims who comprised the majority of the kingdom’s roughly 250,000–300,000 inhabitants were themselves descendants of communities from diverse geographic, social and ethnic backgrounds from across the Iberian Peninsula (and beyond), the consequence of centuries of acculturation, conversion and migration in the region. Granada was also home to various Jewish communities, and significant contingents of North African “holy warriors” (ghuzāh) and their families, who played an important role in Nasrid society and politics.

[1] Olivia Remie Constable, Housing the Stranger in the Mediterranean World: Lodging, Trade, and Travel in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2003), 248-249, 297-298, 302-303; Roser Salicrú i Lluch, “The Catalano-Aragonese Commercial Presence in the Sultanate of Granada during the Reign of Alfonso the Magnanimous,” Journal of Medieval History 27 (2001), 289-312.

The Nasrid College was shaped by this dynamic history of cosmopolitanism, cultural exchange and transregional connections. Unlike the medieval Middle East, where colleges were ubiquitous, particularly from the 11th century onwards, the institution was a rather late arrival in medieval Islamic Spain and North Africa. It was the mosque, the home and the chancery that functioned as the most important spaces of learning prior to the 14th century. The first madrasas (colleges) in the Islamic West only began to be constructed by the Marinids during the late 13th century.[5] The Marinid dynasty in North Africa was particularly distinguished by a dedication to the construction of colleges during the late 13th and 14th centuries. The emergence of the college in late medieval Islamic West reflected the increased collaboration and intersection between learned elites, urban notables and ruling elites. From the inception of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, royal and noble elites worked closely with the urban scholarly and administrative classes whom they relied upon to govern and rule. These elites patronized various intellectual disciplines and genres of writing, ranging from philosophy and medicine to historiography, jurisprudence, and literature. The second Nasrid ruler, Muḥammad II (r. 1273–1302), was even known as “the learned” (al-faqīh)[6] for his patronage, promotion and participation in the Islamic legal, theological and intellectual sciences. It was within a broader cultural milieu in which learning and knowledge served not only a practical purpose in royal courts, but came to constitute a central component of political legitimation, that the Nasrid College, one of the most important institutions in Nasrid history was constructed. In Muḥarram 750/April 1349, the Nasrid College, located directly across from the former Great Mosque of Granada (today the cathedral) and near the main market, was completed.[7]

Return next week to continue reading about the Nasrid College and how it fostered knowledge and power in medieval Granada!

Mohamad Ballan

Mellon Fellow, Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame (2021-2022)

Assistant Professor of History

Stony Brook University

Further Reading

Abu Rihab, Muhammad al-Sayyid Muhammad. al-Madāris al-Maghribīyah fī al-ʻaṣr al-Marīnī : dirāsah āthārīyah miʻmārīyah. Alexandria: Dār al-Wafāʼ li-Dunyā al-Ṭibāʻah wa-al-Nashr, 2011.

Acién Almansa, Manuel. “Inscripción de la portada de la Madraza.” Arte Islámico en Granada, pp. 337-339. Granada, 1995.

Al-Shahiri, Muzahim Allawi. al-Ḥaḍārah al-ʻArabīyah al-Islāmīyah fī al-Maghrib : al-ʻaṣr al-Marīnī. Amman: Markaz al-Kitāb al-Akādīmī, 2012

Bennison, Amira K ed. The Articulation of Power in Medieval Iberia and the Maghrib. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Buresi, Pascal and Mehdi Ghouirgate. Histoire du Maghreb medieval (XIe–XVe siècle). Paris: Armand Colin, 2013

Cabanelas, Dario. “La Madraza árabe de Granada y su suerte en época cristiana,” Cuadernos de la Alhambra, nº 24 (1988): 29–54

________. “Inscripción poética de la antigua madraza granadina” Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos Sección Árabe-Islam 26 (1977): 7-26.

Ferhat, Halima. “Souverains, saints, fuqahā’.” al-Qantara 18 (1996): 375–390

Harvey, Leonard Patrick. Islamic Spain, 1250–1500. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990

Le Tourneau, Roger. Fez in the Age of the Marinides. University of Oklahoma Press, 1961

Makdisi, George. “The Madrasa in Spain” http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/remmm_0035-1474_1973_num_15_1_1235

Mattei, Luca. “Estudio de la Madraza de Granada a partir del registro arqueológico y de las metodologías utilizadas en la intervención de 2006.” Arqueología y Territorio 5 (2008): 181-192

Prado García, Celia. “Los estudios superiores en las madrazas de Murcia y Granada. Un estado de la cuestión.” Murgetana 139 (2018): 9-21.

Rodríguez-Mediano, Fernando. “The Post-Almohad Dynasties in al-Andalus and the Maghrib.” In The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume II: The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, edited by Maribel Fierro, pp. 106–143. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Rubiera Mata, María Jesús. “Datos sobre una ‘Madrasa’ en Málaga anterior a la Naṣrí de Granada.” Al-Andalus 35 (1970): 223–226

Sarr, Bilal and Luca Mattei. “La Madraza Yusufiyya en época andalusí: un diálogo entre las fuentes árabes escritas y arqueológicas.” Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 16 (2009): 53–74.

Secall, M. Isabel Calero. “Rulers and Qādīs: Their Relationship during the Naṣrid Kingdom.” Islamic Law and Society 7 (2000): 235–255

Seco de Lucena Paredes, Luis. “El Ḥāŷib Riḍwān, la madraza de Granada y las murallas del Albayzín.” Al-Andalus 21 (1956): 285–296.

Simon, Elisa. “La Madraza Nazari: Un centro del saber en la Granada de Yusuf I.” https://andalfarad.com/la-madraza-nazari/

[1] For some significant studies of the Alhambra, see Olga Bush, Reframing the Alhambra: Architecture, Poetry, Textiles and Court Ceremonial (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018); Antonio Malpica Cuello, La Alhambra: Ciudad Palatina Nazarí (Malaga: Editorial Sarria, 2007); Antonio Fernández-Puertas, La fachada del Palacio de Comares (Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra, 1980); Oleg Grabar, The Alhambra (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978); Antonio Gallego y Burín, La Alhambra (Granada: Editorial Comares, 1963); Basilio Pavon Maldonado, Estudios sobre la Alhambra (Granada: Patronato de La Alhambra, 1975); Leopoldo Torres Balbás, La Alhambra y el Generalife (Madrid: Editorial Plus-Ultra, 1953).

[2] For a general discussion of this question, see George Makdisi, “The Madrasa in Spain,” Revue de l’Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée 15–16 (1973), pp. 153–158 http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/remmm_0035-1474_1973_num_15_1_1235

[3] For an important recent contribution, which reflects the most up-to-date scholarship on Nasrid Granada, see Adela Fábregas, ed., The Nasrid Kingdom of Granada between East and West (Leiden, 2021). A significant historiographical overview and the current state of the field can be found in Antonio Peláez Rovira, “Balance historiográfico del emirato nazarí de Granada (siglos XIII-XV) desde los estudios sobre al-Andalus: instituciones, sociedad y economía,” Reti Medievali Rivista 9 (2008), 1–48.

[4] Olivia Remie Constable, Housing the Stranger in the Mediterranean World: Lodging, Trade, and Travel in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2003), 248-249, 297-298, 302-303; Roser Salicrú i Lluch, “The Catalano-Aragonese Commercial Presence in the Sultanate of Granada during the Reign of Alfonso the Magnanimous,” Journal of Medieval History 27 (2001), 289-312.

[5] For an excellent recent study of this development see Riyaz Mansur Latif, Ornate Visions of Knowledge and Power: Formation of Marinid Madrasas in Maghrib al-Aqsā (University of Minnesota PhD Book, 2011). Also, see Muhammad Abu Rihab, al-Madāris al-Maghribīya fī al-ʻaṣr al-Marīnī : dirāsa āthārīya miʻmārīya (Alexandria: Dār al-Wafāʼ li-Dunyā al-Ṭibāʻa wa-al-Nashr, 2011).

[6] This was an epithet he shared with his exact contemporary, Alfonso X of Castile-León (r. 1252-1282), known as “the Learned” (El Sabio).

[7] The most important scholarship about the Nasrid College includes La Madraza: pasado, presente y futuro (Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada, 2007), eds. Rafael López Guzmán and María Elena Díez Jorge; La Madraza de Yusuf I y la ciudad de Granada: análisis a partir de la arqueología (Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada, 2015), eds. Antonio Malpica Cuello and Luca Mattei.