The Roman Pontiffs, over the course of the second half of the Middle Ages, were not noteworthy for their enthusiasm for the liturgical rites of the Eastern Christian Churches. In few cases was this made clearer than in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, an especially distasteful moment of intra-Christian violence that left the Latin crusaders, originally destined for the Holy Land, instead governing the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire. Although he initially decried the violence, Innocent III, then the Pope of Rome, quickly attempted to eradicate some of the liturgical differences that had plagued relations between the Roman and Constantinopolitan Churches for the previous century and a half, ever since the ill-fated trip of Cardinal Humbert and his co-legates to Constantinople in 1054. Among other changes, all new bishops, whether Greek or Latin, were to be consecrated according to the Roman rite, Latin clergy were to be appointed to those churches that had been abandoned by Greek priests fleeing the crusaders, and those Greek clergy who remained were to be encouraged to switch to the Latin rite for the celebration of the Eucharist [1]. Although he was not privy to the election of Thomas Morosini as the (Latin) Patriarch of Constantinople in the wake of the city’s conquest, he quickly confirmed him in his office and clarified that he would have the traditional jurisdictional authority of the Constantinopolitan See [2]. All of this transpired prior to the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, with its famous canon dealing with “the pride of the Greeks against the Latins.”

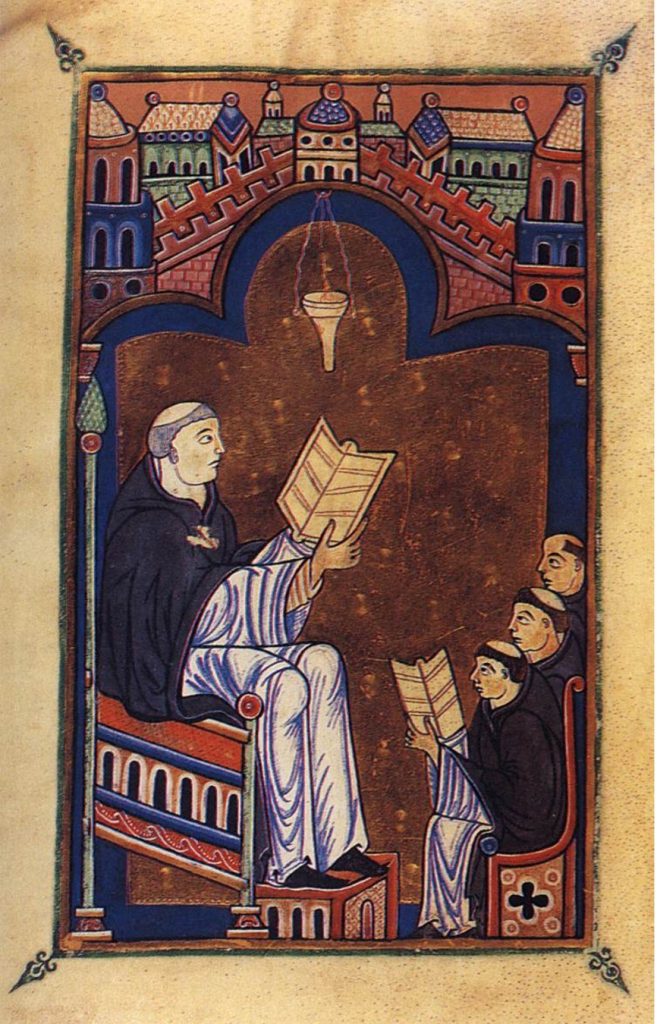

Pope Innocent III, from the Monastery of Sacro Speco of Saint Benedict – Subiaco (Rome).

Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

This policy, in fact, marked a sharp deviation from Innocent’s prior treatment of the Greek rite. Too easily forgotten is the fact that the Greeks had a substantial presence in much of the Italian peninsula (and to this day there exists in Italy a few thousand people who speak Griko, essentially a dialect of medieval Greek). Alongside this substantial Greek population were Greek-rite monastic establishments and a number of dioceses served by Greek prelates, all of which were under the ultimate jurisdiction of the See of Rome. Innocent III, in his dealings with these communities prior to the Fourth Crusade, was noticeably less aggressive, balancing his apparent preference for the Latinization of ordination rites with a policy of non-interference on the matter of clerical marriage and active support for Basilian monasteries under his jurisdiction [3].

It has been popular with some modern commentators, Joseph Gill being perhaps the foremost example, while admitting that Innocent III had a distinct preference for the Latin rite, to argue that he was primarily concerned with enforcing (Latin) canon law. In this reading, the chief concern of the papacy was the allegiance of the Eastern clerics; once that had been secured, the secondary priority was to extirpate practices that were actively contrary to the law of the Roman church while at the same time tolerating, to a greater or lesser degree, ritual aspects that didn’t interfere with canonical norms [4].

To see whether this was in fact the case, helpfully, there are two other points of comparison. The activity of the crusaders in the Levant occasioned a resumption of active communication and communion between the Papacy and the Maronite Church. As part of this exchange, Innocent III issued a papal bull in January of 1215 in which he formally accepted the Maronite Church and confirmed several of its privileges. At the same time, though, he demanded certain changes: the Maronite Church must maintain the truth of the filioque, that only a single invocation of the Trinity be made during the rite of baptism, that the sacrament of Chrismation/Confirmation be done only by a bishop, and that the bishops wear vestments according to the Roman use [5]. In Bulgaria, facing a tsar and a primate eager to secure legitimacy for their positions and the autocephaly of the Bulgarian church, the subordination to Rome likewise came with a demand. As in Constantinople following the Latin conquest and in some of the Greek communities in the south of the Italian peninsula, the Roman rite was to be used for the ordination of priests and bishops [6].

These distinct differences in approach gives rise to the obvious questions: Did Pope Innocent III have a consistent stance toward the liturgical rites of the Christian East and, if so, what was it? Is it really fair to suggest that the pope was motivated first, by the question of allegiance, and second, to matters of ritual? Perhaps this was the case, but my sense is that the matters were more closely linked than many commentators assume. My suspicion is that, for Innocent, the willing submission of various Greeks, Bulgarians, and Lebanese to aspects of the Roman rite was itself the proof that they also accepted papal authority more broadly. I think that modern scholarship often fails to appreciate the intimate connection between practice and belief — lex orandi, lex credendi, after all — and that this is especially the case when it comes to the ritual differences that divided the churches of Rome and Constantinople. By requiring concrete changes in ritual practice, down to the style of vestments to be worn by the Maronite clergy, Innocent III caused these churches to give physical, tangible proof that they accepted the teaching, jurisdictional, and legal authority of the Apostolic See.

Nick Kamas

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

- Summarized by Alfred Andrea, “Innocent III and the Byzantine Rite, 1198–1216,” in Urbs capta: La IVe croisade et ses conséquences, ed. Angeliki Laiou (Paris: Lethielleux, 2005), 118–120.

- Jean Richard, “The Establishment of the Latin Church in the Empire of Constantinople (1204–27,” in Latins and Greeks in the Eastern Mediterranean after 1204 (London: Routledge, 1989), 49.

- Andrea, “Innocent III,” 116–118.

- Joseph Gill, “Innocent III and the Greeks: Aggressor or Apostle?,” in Relations between East and West in the Middle Ages, ed. Derek Baker (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1973), 103–105.

- No. 216, Acta Innocentii III, ed. P. Theodosius Haluščynskyj (Rome: Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1944), 459–460.

- Andrea, “Innocent III,” 117. See also Francesco Dall’Aglio, “Innocent III and South-Eastern Europe: Orthodox, Heterodox, or Heretics?” Studia Ceranea 9 (2019), 20.