Though diverging with regards to detail, most historians of intellectual history would readily acknowledge that the advent of Christian antiquity coincided with a new concept of moral self-governance and, consequently, individual culpability.[1] Antique and medieval Christian thinkers cultivated a universal notion of ethical self-determination, affirming that all possess an inherent and unnecessitated capacity for the recognition and pursuit of the good regardless of one’s social upbringing or physical circumstances. A prima facie examination of these late antique and medieval Christian notions might seem to suggest many common features with post-Enlightenment and contemporary conceptions of moral autonomy, which emphasize self-legislation and independently-derived moral criteria. Nevertheless, a closer reading of these sources discloses a mindset that grounds moral self-determination in an ethic of co-governance, establishing the heteronomous “other” as an indispensable aspect of the quest for the good.

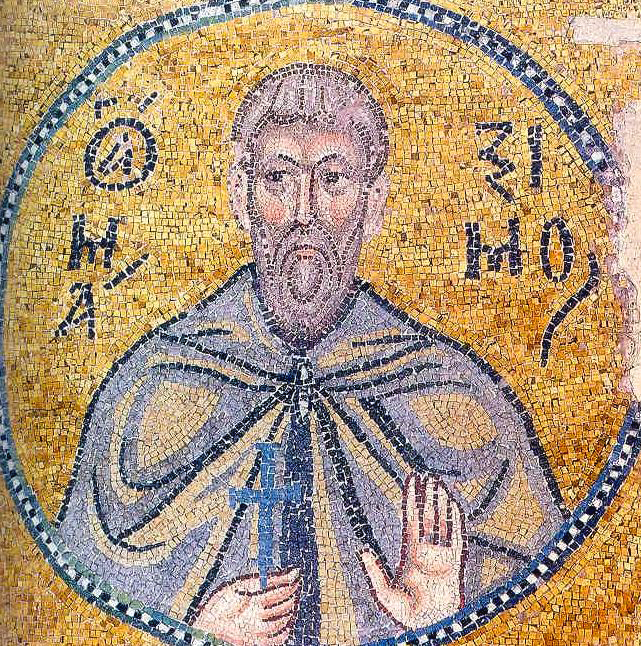

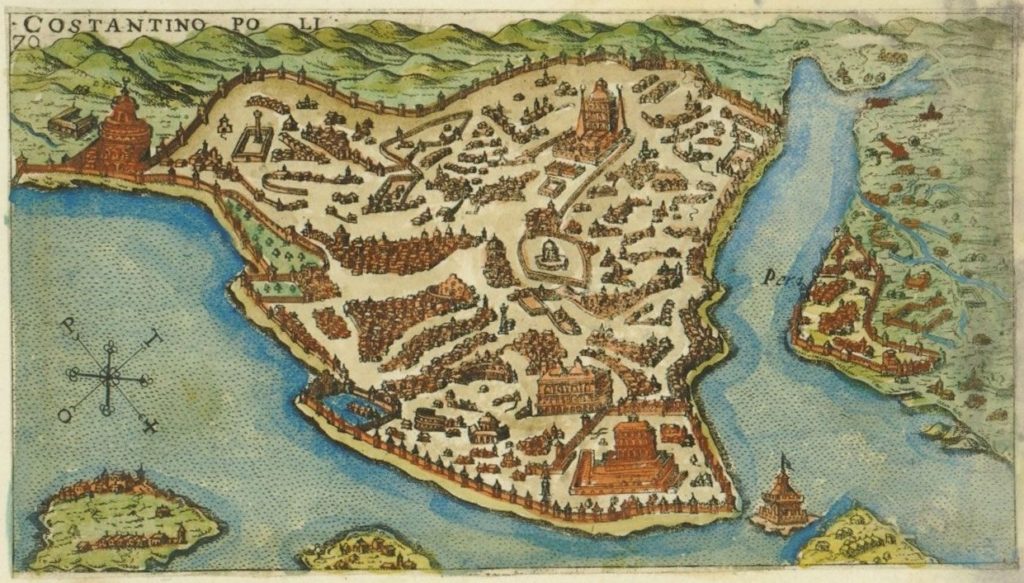

A significant exemplar of this “ethic of co-governance” can be found in the corpus of the early Byzantine monk, Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662 AD), a figure revered by both eastern and western Christian traditions. Imbued with the spirit of the eastern ascetic tradition, the Confessor draws upon both monastic literature and the Hellenic philosophy of the Alexandrian intellectual tradition in order to synthesize his theological vision. Prominent among the doctrines prized by the eastern monastic tradition is indeed the idea that every rational agent possesses a free will, a notion that Maximus himself would also ardently defend and develop. Equally prominent, however, is the practice of “obedience” (hypakoē) to a spiritual guide or superior. This practice became an indispensable aspect of spiritual life in the eastern monastic communities that coalesced in the fourth and fifth centuries, and it remained a venerated feature of eastern monasticism through the end of the Byzantine era. Though not a central motif in his spiritual writings, Evagrius of Pontus (345–399 AD), a pioneer of eastern monasticism, is careful to exhort both male and female monastics living in community to attend to the words of their spiritual guides.[2]

The most well-known literary source providing an exposition of obedience is The Ladder of Divine Ascent, authored by John of Sinai (c.579–659 AD).[3] In the fourth chapter or “step,” John addresses the practice, defining it thusly: “Obedience is absolute renunciation of our own life, clearly expressed in our bodily actions…Obedience is the tomb of the will and the resurrection of humility.”[4] His endorsement of the renunciation of “will” may sound odd to many readers, especially given the Christian emphasis upon moral self-governance. Nevertheless, John is not denying the concept of free will as such, nor is he suggesting that the volitional faculty must atrophy into non-existence. Scholarly evidence suggests that the term John uses here for “will,” thelēma or thelēsis, comes to be associated with the volitional faculty in a philosophical sense in the writings of Maximus the Confessor, whose engagement with the Christological controversies of the seventh century provided the impetus for the standardization of the expression.[5] Thus, when John speaks of “will” and its denial, he is arguably referring to what Maximus the Confessor and his theological progeny would call gnomē, which in the idiom of the time refers to a private or particular disposition of will, or even to a personal opinion.[6] John’s monk is not so much denying his own intrinsic freedom of will as he is seeking the co-governance and insight of those who are more advanced in virtue, and, through them, struggling to direct his volitional disposition such that it harmonizes with the other members of the community.

Maximus discloses a similar approach to moral self-determination by establishing his ethical teaching on “love” or agapē, which figures prominently in his philosophical and dogmatic treatises as well as his ascetic writings.[7] Agapē is no mere private sentiment but constitutes the impetus and ground for moral practice as a whole, thereby suggesting that moral judgment and orientation presuppose an awareness of one’s community and the persistent presence of a real, tangible “other.” In this way, Maximus retools an older Aristotelian paradigm, exchanging justice for love as the central and all-defining virtue.[8] Insofar as agapē is the chief virtue, narcissistic self-love, or filautia, is its inverse and the progenitor of all vice. As he demonstrates in one of his earliest works, The Ascetic Life, ascetic discipline should not be considered a private enterprise intended primarily for the sake of internal moral perfection.[9] Rather, its purpose is the effacement of filautia and the diachronic restoration of temporal and eternal relationships with the creator and one’s fellow creatures. To quote the Confessor directly: “He who is unable to separate himself from the passionate yearning for material things shall neither love God nor his neighbor authentically.”[10] Defining this activity in ontological terms, Maximus argues that divine love shall eschatologically gather together the fragmented portions of human nature into a functional unity, existing as a single mode in solidarity of will and disposition.[11] If love is the metaphysical impetus for the pursuit of virtue and the ground of morals, mimēsis or “imitation” is the pedagogical means by which it is recognized and acquired. Creatively appropriating and redeploying principles of Neoplatonic philosophy, the Confessor establishes the imitatio Christi, the existential imitation of Christ and his virtues, as the epistemological core of his ethics.[12] True followers of Christ imitate his mode of existence, disclosing through their lives and examples divine virtue. The lives and modes of these “exact imitators” are in turn imitated and imparted unto the morally immature.[13]

When viewed through a contemporary lens, we might say that Maximus’ view and the tradition that informs him entail the recognition of “autonomy”—as we would construe it now—as the point of departure for human agency. However, the ideal of agapē calls for the voluntary sacrifice of autonomous moral space for the sake of moral co-governance and a reciprocal unity of wills, which depends upon the concrete example of Jesus Christ and his “exact imitators.”

Demetrios Harper

Byzantine Studies Post-doctoral Fellow

[1]This is strongly reaffirmed by Kyle Harper (From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity[Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2013], 80-133), who objects to Michael Frede’s assertions that the concept of free will is not unique to the Christian tradition but can, in fact, be attributed to Epictetus. See Frede’s A Free Will: Origins of the Notion in Ancient Thought, Sather Classical Lectures 68, ed. A. A. Long(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 66-88.

[2]See The Two Treatises: To Monks in Monasteries, and Exhortation to a Virgin, in Evagrius of Pontus: The Greek Ascetic Corpus, trans. Robert Sinkewicz (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 127-28, 131.

[3]These dates are based on what still remains tentative conjecture. Cf. Alexis Torrance, Repentance in Late Antiquity: Eastern Christian Asceticism and the Framing of the Christian Life c. 400-650 CE (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 158-60.

[4]The Ladder of Divine Ascent 4.3, revised edition, trans. Lazarus Moore (Boston, MA: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 1991), 21. For the original text, I consulted the Κλίμαξ, in Ἰωάννου τοῦ Σιναΐτου ἅπαντα τὰ ἔργα, Φιλοκαλία τῶν νηπτικῶν καὶ ἀσκητικῶν πατέρων 16, ΕΠΕ, Ἐλευθέριος Μερετάκη (Θεσσαλονίκη Πατερικαὶ Ἐκδόσεις Γρηγόριος ὁ Παλαμᾶς, 1996).

[5]John D. Madden is among the first to argue for the originality of Maximus’ contribution to the genealogy of the concept of will. Cf. his “The Authenticity of Early Definitions of Will (thelēsis)” in Maximus Confessor: Actes du Symposium sur Maxime le Confesseur, Fribourg (2-5 Septembre 1980), eds. Felix Heinzer and Christoph Schönborn (Fribourg: Éditions Universitaire Fribourg, 1982), 61-82. Madden’s “originality thesis” is defended by David Bradshaw, St Maximus the Confessor on the Will, in Knowing the Purpose of Creation Resurrection, Proceedings of the Symposium on St Maximus the Confessor, ed. Maxim Vasiljević (Alhambra: Sebastian Press, 2013), 143–58 For an up-to-date and comprehensive overview of Maximus’ view, see Ian McFarland, “The Theology of Will,” in The Oxford Handbook of Maximus the Confessor, eds. Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 516-32.

[6]Ian McFarland, “The Theology of Will,” 520-522. Cf. for the context and background of “will” and its correlative expressions in Maximus, cf. Paul Blowers, Maximus the Confessor: Jesus Christ and the Transfiguration of the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 156-65.

[7]Cf. Maximus’ Four Hundred Texts on Love, in The Philokalia, eds. and trans. Kallistos Ware et al., vol. 2 (London: Faber and Faber, 1981), 48-113; Letter 2: On Love,in Maximus the Confessor,The Early Church Fathers, trans. Andrew Louth (Abingdon: Routledge, 1996), 84-93.For a systematic account of Maximus’ aretology and its foundations, see Demetrios Harper, Chapter 4, The Analogy of Love: St. Maximus the Confessor and the Foundations of Ethics(Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2018).

[8]See Maximus’ Quaestiones ad Thalassium I 40.60-70, Corpus Christianorum, Series Graeca 7, eds. C. Laga and C. Steele (Turnhout: Brepols, 1980), 269-71.

[9]Liber asceticus 100-115, CorpusChristianorum, Series Graeca40, ed. P. Van Deun (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000), 17. Cf. also the introduction to the Quaestiones ad Thalassium I 380-390, 39-41.

[10]Liber asceticus 100-110, 17. The translation is mine.

[11]Letter 2: On Love, 88.

[12]Cf. St. Maximus the Confessor’s Questions and Doubts III, 1, trans. Despina Prassas (DeKalb: Northern Illinois Press, 2010),156-57;Ambiguum 48.6,in On Difficulties in the Church Fathers II, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 29, ed. and trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 218-20.

[13]Liber asceticus 635-665, 73-74.