Medieval women visionary authors are generally known for their evocative poetry and prose, prophetic missions of reform, and intimate relationship with Christ. Can we imagine a visionary who might be better known for…reading the Bible?

For about four years, starting around 1417, a Nuremberg lay woman named Katharina Tucher recorded a spiritual journal of sorts. It consists of ninety-four entries, most of which are visions or auditory lessons from Christ. [1] The abrupt end to the journal in 1421–without announcement, warning signals, or codicological signs of missing folios—continues to puzzle scholars. The cessation of the Offenbarungen, as the text is known today, is even more curious in light of the evidence for the ongoing strength of Tucher’s spiritual life. She accumulated a prodigious library of religious texts, copied some of them herself, and ended her days as a (probably) lay sister in the prestigious Dominican convent of St. Katherine’s in Nuremberg. [2]

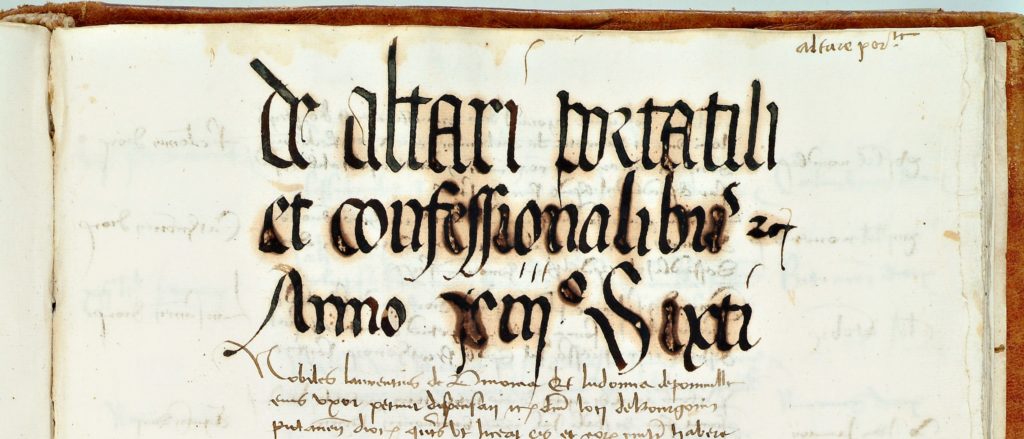

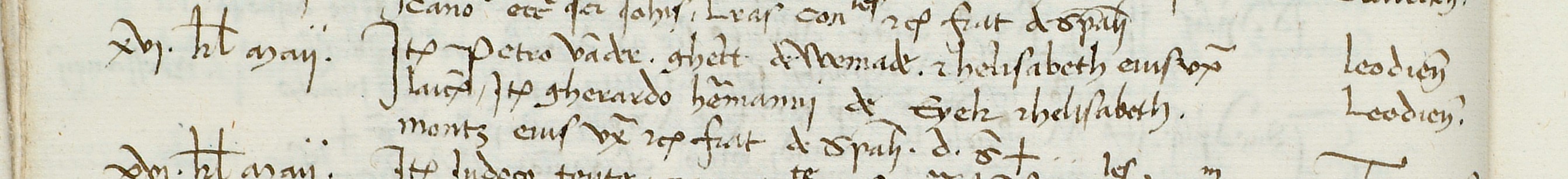

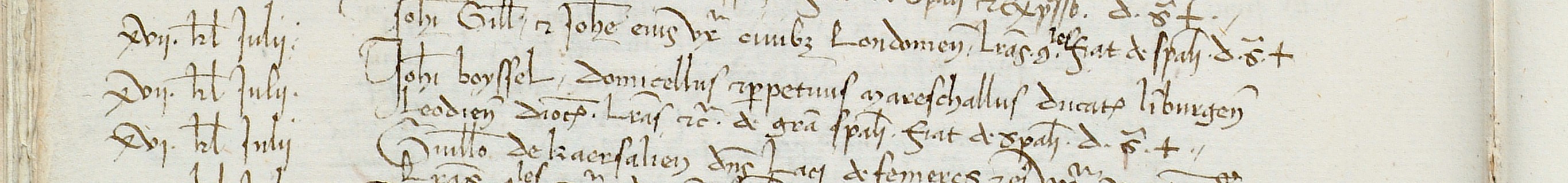

It’s possible Tucher hid her Offenbarungen from her sisters, but she certainly did not hide her library. She brought her books to a bookish convent, and the nuns’ desire to read, use, and copy their books is why we know about her book collection in the first place. In 1455, Sister Kunigunde Niklasin embarked on a project to catalogue the convent library’s vernacular holdings, using an alphanumeric scheme to identify books by type and subject matter. [3] By the end of the century, the catalogue counted off 352 codices (out of an estimated 500-600 in the convent library total). Twenty-six of these contained exclusively or primarily texts that Tucher donated, sixteen of which survive today. The contents of the others are known through the nuns’ notations in the library catalogue. [4]

Scholars who include Tucher’s personal book collection in their analyses of monastic or lay literary culture have typically focused on three things. First, of course, its unusual size—twenty-six books is the single largest donation to St. Katherine’s by any one person—and her own involvement as scribe of some of those. Second, for two of its most surprising contents. Tucher’s Schwabenspiegel was one of just a handful of non-religious works listed in the convent catalogue. [5] She also brought with her a German translation of William of St. Thierry’s Epistola ad fratres de Monte Dei, a guide to monastic life that includes instruction on how to read for spiritual advancement. [6] While its relevance to her recipients is clear, Tucher’s copy is the only one surviving with definite lay provenance.

The third characteristic frequently described by scholars, in contrast to the last point, is just how comprehensively typical the spread of books is. [7] If Tucher’s library were songs (and in fact, it includes a number of hymns), it could be a late-night infomercial “Golden Hits of the Late Middle Ages” 3-disc set. Many of the manuscripts are miscellanies that mix together prayers, sermons, short didactic works, and excerpts from longer texts. She had five prayer books plus a Psalter–possibly the most popular genre in lay ownership, if the number of monks and nuns who brought a personal prayer book with them to their convent is any guide. [8]

Tucher donated no complete Bible or Testament. But the holy book was well represented in its most popular late medieval devotional forms.[9] She brought with her an Old Testament of a historiated (narrative) Bible with the parallel readings for Sundays marked off, two Gospel harmonies to represent the New Testament, and the Psalter mentioned earlier. She also had a pericope containing the liturgical readings from the Gospels and epistles in German, a genre that many fifteenth-century laity used to follow along with the readings at Mass. [10]

When it came to longer didactic texts, she owned works like Henry Suso’s Little Book of Eternal Wisdom (plus an additional excerpt from it as an Ars moriendi text), Rudolf Merswin’s Neunfelsenbuch, and Otto von Passau’s Die 24 Alten. Marquard von Lindau, whose importance for late medieval literary culture has recently been illuminated by Stephen Mossman, was a favorite author—Tucher had two copies of his Dekalogstraktat as well as one each of his commentary on Job and teachings on the Eucharist. [11] The hagiographies are well situated in her southern German context: Elisabeth of Hungary, Catherine of Siena, a collection of antique saints from the area around Nuremberg.

For the most part, then, Tucher owned books that we might expect a wealthy, devout fifteenth-century woman to own. To focus on categories of genre, however, overlooks one of the most important patterns in her reading interests: regardless of specific texts’ focus, how persistently biblical her overall spiritual and literary orientation were.

Looking for Part 2? Find it here.

Cait Stevenson, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

[1] Katharina Tucher, Die Offenbarungen, ed. Ulla Williams and Werner Williams-Krapp

[2] The most comprehensive biographical account of Tucher is found in the introduction to Williams and Williams-Krapp’s critical edition. See Williams and Williams-Krapp, introduction to Die ‘Offenbarungen’ der Katharina Tucher (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1998), 1-27.

[3] On the library of St. Katherine’s, see Marie-Luise Ehrenschwendtner, “A Library Collected by and for the Use of the Nuns: St. Catherins’ Convent, Nuremberg,” in Women and the Book: Assessing the Visual Evidence, ed. Lesley Smith and Jane H.M. Taylor (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 123-132. Karin Schneider, “Die Bibliothek des Katharinenklosters in Nürnberg und die städtische Gesellschaft,” in Studien zum städtischen Bildungsgewesen des späten Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit, ed. Bernd Moeller et al. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1983), 70-82, discusses how Tucher’s selection of books fits in with the convent library overall, and compares her donation to that of other prominent sisters.

[4] A list of codices and contents, including the catalogue entries of the lost manuscripts, can be found in Williams and Williams-Krapp, “Introduction.”

[5] This was first brought to scholarly attention by Volker Honemann, Die ,Epistola ad fratres de Monte Dei’ des Wilhelm von Saint-Thierry: Lateinische Überlieferung und mittelalterliche Übersetzungen (Zürich: Artemis, 1978), 121, and discussed further in Schneider, 74.

[6] Cynthia Cyrus, The Scribes for Women’s Convents in Late Medieval Germany (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 112.

[7] See, for example, Schneider, 73-75.

[8] Thomas Lentes, “Prayer Books,” in Transforming the Medieval World: Uses of Pragmatic Literacy in the Middle Ages, ed. Franz-Josef Arlinghaus et al., (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006) 242-243.

[9] Sandra Corbellini et al., “Challenging the Paradigms: Holy Writ and Lay Readers in Late Medieval Europe,” Church History and Religious Culture 93 (2013): 171-188.

[10] Ibid., 177-178

[11] Stephen Mossman, Marquard von Lindau and the Challenges of Religious Life in Late Medieval Germany: The Passion, the Eucharist, and the Virgin Mary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

The fifteenth-century hagiography of Elisabeth Achler, a Franciscan tertiary from Reute, ascribes to her the standard catalogue of proper saintly elements. She could almost be the exemplar of a late medieval holy woman. But her hagiographer, Augustinian prior Konrad Kügelin, does not stop with standard recitations of virtues and somatic spirituality. In almost every category, Achler is said to exceed even the most frenetic reports of her role models’ own deeds.

The fifteenth-century hagiography of Elisabeth Achler, a Franciscan tertiary from Reute, ascribes to her the standard catalogue of proper saintly elements. She could almost be the exemplar of a late medieval holy woman. But her hagiographer, Augustinian prior Konrad Kügelin, does not stop with standard recitations of virtues and somatic spirituality. In almost every category, Achler is said to exceed even the most frenetic reports of her role models’ own deeds.