Don't forget to read Part 1 of this post here.

The collection of books that Nuremberg widow Katharina Tucher donated to her new convent around 1440 offer a stunning snapshot of one woman’s religious literary interests. Tucher’s books included the sorts of works one would expect to see in the library of a wealthy fifteenth-century reader: prayer books, Henry Suso’s Büchlein der ewigen Weisheit, hagiographies of popular female saints. One particularly noteworthy feature of her collection, however, transcends any one text or genre: the sheer amount of biblical and biblically-derived material.

Her most straightforwardly biblical books, mentioned in the previous post, are also distinguished by their utility: one text meant for use at Mass, a second turned into such, a book for praying. But we also find the reverse situation—texts from popular genres have a Scripture-based parallel in Tucher’s collection. She owned prophecies of the Sibyl and Birgitta of Sweden—and a collection gathered from the Old Testament. Of the devotional poem Christus und die minnende Seele, which scholars have demonstrated had a deep influence on the Offenbarungen, what accompanied Tucher to St. Katherine’s was an excerpt glossing the Book of Esther. [12] For moral instruction, she had treatises on the traditional categories of virtue and vice like Von der Keuschenheit—but also two copies of Marquard’s treatise on the increasingly popular way to structure moral teaching instead, the Ten Commandments. [13]

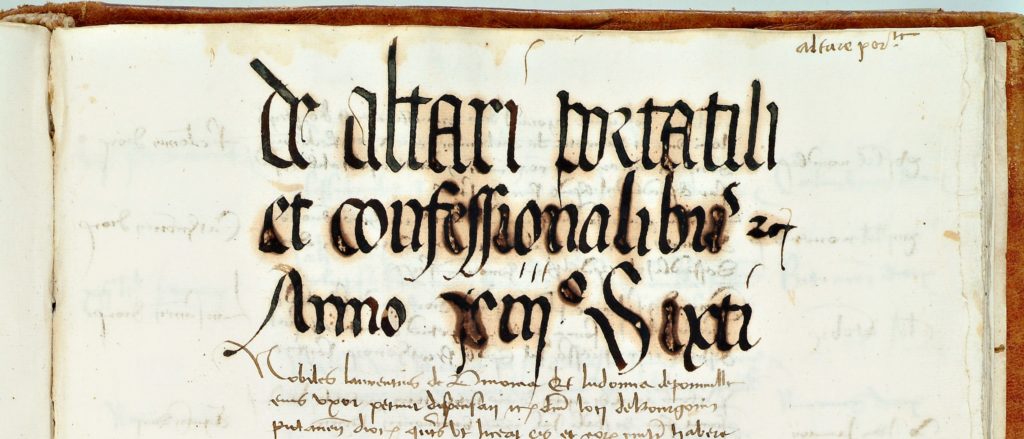

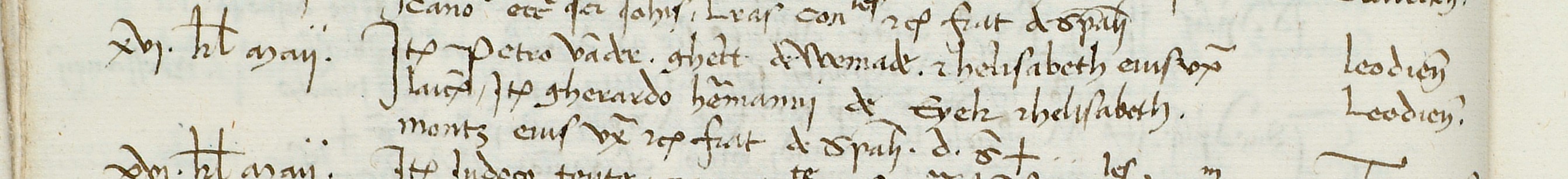

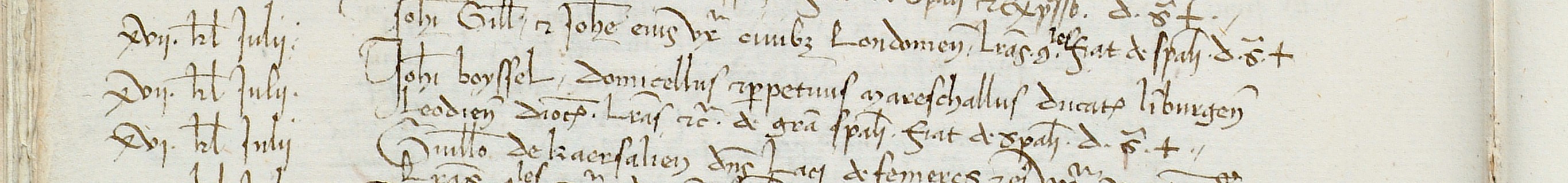

Perhaps most intriguing of all is Tucher’s portion of MS Strasbourg, Bibliotheque Nationale et Universitaire, cod. 2195. She herself wrote 104v and 138v-148v. Of these, 139r-142r and 147r-148v match the contents of an unrelated manuscript in the Nuremberg city library. These folios contain a smattering of spiritual advice attributed to authors like Augustine and Bernard of Clairvaux, along with some German prose versions of hymns like Veni spiritus sancti. [14]

104v and 142v-146v, however, were either added by Tucher when she copied an exemplar, or subtracted by the other scribe when they copied hers. The texts that Tucher felt were necessary to include, that the other author did not? From 104v, an excerpt from the letter to the Colossians (Col 3:1-4). From 142v-146v, a short text attributed to Bernard, and three more hymns modified into German prose. Those hymns were the Magnificat from Luke and two passages of the praise of Wisdom from Sirach. [15]

As with the examples in other genres, the Bible-based hymn variations that Tucher included in cod. 2195 matched non-biblical material in her library, in this case, in the same manuscript. They stand out not in their message but in their origin.

There are two key points here. First, the biblical material in Tucher’s personal library was useful. From a historiated Bible marked out for reference according to use in the liturgy to framing her sins and successes with the Ten Commandment, Scripture was present as a means rather than an end. Second, much of the Bible’s shadow over her book collection is in fact “biblical material,” rather than full Bibles or narrative equivalents. The distinction of these texts from their non-biblical partners was clear in the Middle Ages as today—the nuns of St. Katherine’s, for example, categorized didactic texts based on the Ten Commandments and other biblical structures (B) immediately after Bibles (A). [16] Biblical material did not necessarily add new teachings to the devotional life of its readers. It did, however, offer a different foundation for those teachings. And as the rising prominence of the Decalogue in moral teaching shows, this particular foundation was more and more important as the fifteenth century progressed.

Recent scholarship has finally grown more comfortable discussing the perfectly orthodox presence of vernacular Scripture in the fifteenth century, including in lay readers’ hands. The “Holy Writ and Lay Readers” project, although it does not at present cover southern Germany, has proven especially helpful in emphasizing the different formats that the “Bible” could take. Leaders Sandra Corbellini, Mart van Duijn, Suzan Folkerts, and Margriet Hoogvliet write:

The focus on the “completeness” of the text does not take into account the specific practice of diffusion of the biblical text…often delivered…in the form of passages and pericopes. Moreover, the stress on “complete Bibles” does not fully acknowledge the importance of the connection with the liturgy in the approach of lay people to the biblical text. In fact, the participation in the liturgy and the reading of biblical pericopes following the liturgical calendar…offer the most important and valuable means of access to the Scriptures.

The selection of biblical texts and liturgical rearrangements should be taken as…an indication of a specific use and approach, determined by the needs and the interests of the readers. [17]

To frame lay reading of the Bible as “functional,” as Corbellini et al. describe with respect to liturgical use, indicates an active and conscious engagement with peri-biblical text as Scripture. In this light, Katharina Tucher’s book collection suggests that our understanding of “the vernacular Bible” in the fifteenth century might be broadened even further. The pericope and marked-up historiated Bible in her library were useful. So were her Psalter, moral instruction organized according to the Ten Commandments, and biblical hymns presented as prayer. These texts, in their functionality, also represent an active and conscious engagement with the Bible.

Only by studying the many forms of the Bible’s presence in Tucher’s library, therefore, can we begin to understand its place in her spiritual life. I have described her reading interests as “comprehensively typical,” but at the same time, she added biblical material to a miscellany where another scribe omitted it. How “typical,” then, was she? By casting the same wider gaze over biblical material in fifteenth-century literary culture, we can better understand how a lay person interacted with the religious world of their day—a pressing question for Tucher’s era in particular. And indeed, only by accounting for all dimensions of biblical material can we grasp the changing place of the Bible in fifteenth-century religious culture.

Cait Stevenson, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

[12] On Tucher’s use of Christus und die minnende Seele, see most comprehensively Amy Gebauer, ‘Christus und die minnende Seele’: An Analysis of Circulation, Text and Iconography (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2010).

[13] On the Decalogue’s gradual replacement of the seven deadly sins as the foremost means to teach morality, see Robert Bast, Honor Your Fathers: Catechisms and the Emergence of a Patriarchal Ideology in Germany, 1400-1600 (Leiden: Brill, 1997); John Bossy, “Seven Sins into Ten Commandments,” in Conscience and Casuistry in Early Modern Europe, ed. Edmund Leites (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 214-234.

[14] Williams and Williams-Krapp, “Introduction,” 18.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ehrenschwendtner, 126.

[17] Corbellini et al., 177-178.